When it comes to the relationship between the Bolsheviks and monarchs, the arrest and subsequent murder of Tsar Nicholas II and his family quickly come to mind. However, in other communist-occupied countries, such as Bulgaria and Romania, monarchs were allowed to abdicate and secretly go abroad. What was it like in Poland?

by Wojciech Stanisławski

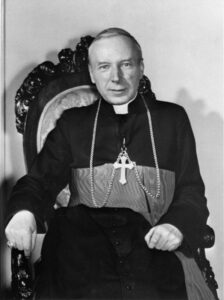

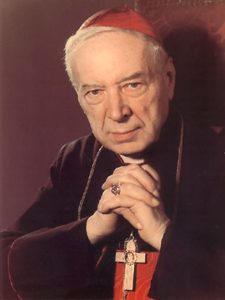

Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński did not come from a royal family. His father was an organist in a village church. However, since the middle of the 16th century, the Primate of Poland has held the title of “interrex”, replacing the monarch during his illness or death. This title was formally abolished after the partitions of the Republic of Poland, but people tended to refer to the “monarchical role” of the primates while the country was in captivity – during the partitions, both world wars and after 1945.

Therefore, the decision of the Communist authorities to arrest Wyszyński in September 1953, more than half a year after Stalin’s death, was very symbolic. Seemingly, this decision ended several years of strife between the authorities and the Church. It is true that, by deciding to arrest Wyszyński, the strife ended in the “overturning of the chessboard” but this was the end of it: there was no Primate and no opponent. However, as it turned out, this move only strengthened the authority of the Church in the People’s Republic of Poland. Thirty-seven months later, in October 1956, Cardinal Wyszyński was released from internment, and, until his death in 1981, he remained an informal but unquestionable interrex in a socialist country.

Communists and the Catholic Church

The fact that there must have been a “test of strength” between the authorities established in Poland after the war and the Catholic Church was clear since the establishment of the pro-Moscow government in July 1944. Both the doctrine of Marxism-Leninism and the practice of totalitarian rule during the “mature” Stalinist era did not allow for such an extensive “religious structure”. Meanwhile, the Church was present in public life, impacting (through pastoral ministry and religious teaching) the education of children and youth, exercising exceptional authority, and at the same time being fully independent from the state.

The status of the Church in post-war Poland was special. After the Holocaust, the shifting of the borders due to the Yalta Conference and the displacement of the population, the overwhelming majority of the country’s citizens declared themselves “Catholics”. Virtually everyone living in the countryside was a churchgoer. In the case of the urban population, this percentage was slightly lower, but still, it was usually around 90 percent. The Church also represented the tradition of defending of Polish culture and identity since the time of the partitions – a tradition which in 1945, as everything indicated, the Church would need to take up again. The Church won respect during the war and the occupation, when both the Germans and the Soviets repressed and often exterminated clergymen (out of twelve thousand in pre-war Poland, one fifth has been killed).

In a situation in which the government was eliminating or subordinating successive political and social institutions, from opposition parties to trade unions and authors’ and creators’ associations, the only autonomous institution that remained was the Church. This automatically created a “free space“ even for those who were far from religious commitment. Both sides were aware of this and the communist authorities did not intend to tolerate this anomaly.

Communists versus the Catholic Church

In other countries, for these same reasons, a confrontation with the structures and hierarchies of the Church took place much earlier, and in a more brutal way. The Primate of Hungary, Archbishop József Mindszenty (nota bene, also referring to the interrex tradition by using the honorary title “prince-primate”, “hercegprímás”, especially irritating to Communists) was arrested on Christmas 1948. After two months of interrogation and torture, on 8 February 1949, he was sentenced to life imprisonment after being charged with “national treason.” Earlier, from September 1946, Archbishop Alojzije Stepinac, the head of the Croatian Church, received a heavy sentence and was imprisoned. He was accused of cooperation with the Ustasha authorities collaborating with the Third Reich. In April 1949, the Archbishop of Prague, Josef Beran, was under house arrest, and the heads of the Churches of Albania and Romania were also imprisoned. Earlier, a few weeks after the occupation of these areas by the Red Army, the structures of the Church in the areas directly incorporated into the Soviet Union were practically liquidated.

In Poland, the communist authorities had a hard nut to crack. In addition to the above-mentioned circumstances (the huge number of believers, and the high degree of identification of the Church with patriotic activity), there were no grounds for accusing clergymen of open or quasi-collaborationist activities (which was possible in several other countries of the region). the position of the parliamentary opposition (the Polish People’s Party) and the armed underground forces remained relatively strong in the first years, despite repressions. Firstly, the authorities had to deal with these opponents and weaken social independence, and, until then, the Church had to be respected. At least formally.

Hence, the support from the authorities for rebuilding damaged churches, and the support for the creation of new Church structures for the so-called Recovered Territories that were subordinate to the primate of Poland (this had an important stabilization function, desired from the point of view of the new authorities). In this effort, the Communists often resorted to imitating pre-war gestures, which in the eyes of observers was rather showy and ostentatious. In 1945-1947, the government-controlled press readily published photos of dignitaries (including communist President Bolesław Bierut) participating in ceremonial masses or Corpus Christi processions.

This was about to change. Already in September 1945, the Provisional Government of National Unity dissolved the concordat with the Holy See. More and more demands were made of the Episcopate to “sort out and arrange things in the Vatican”, contrary to centuries-old Church practice, on the issue of appointing new bishops in the Recovered Territories. Various types of nominally Catholic organizations were established, but in reality they were fully loyal to the authorities – from the most famous and most influential Pax Association (in 1947) to groups of priests gathered in veterans’ organizations. However, dozens of issues were potentially controversial, ranging from the seizure (as part of the agricultural reforms) of the Church’s land estates which constituted the source of income for parishes or monastic houses to the closure of Catholic journals and charity associations, and the arrests of priests.

Primate Wyszyński and attempts at compromise

The Communists adopted a hard line for the first time in 1948. It was then that the activists of the Christian Democrats, already marginal by that time, the Labor Party and the editors of the party’s journal “Tygodnik Warszawski” with the priest Zygmunt Kaczyński at its helm were all arrested. It was at that time, after the death of Cardinal August Hlond, the former primate, in October 1948, that Pope Pius XI appointed as his successor the 47-year-old Bishop of Lublin, Stefan Wyszyński.

Bishop Wyszyński, already during his ministry, had managed to edit an important theological journal, offer pastoral care to workers, head a major seminary, and also be the chaplain of the Institute for the Blind in Laski and of a Home Army division. He was soon to experience what the communist “hard line” was like at the end of the 1940s. It was a common experience in all the satellite countries under the control of the Kremlin – in Polish conditions, however, it represents a particularly dynamic campaign against the Catholic Church.

It did not take long for the campaign to begin: on 14 March 1949, just over a month after Archbishop Wyszyński’s ingress to the Warsaw-Gniezno diocese (which meant taking the primate’s dignity), the government issued a statement. It criticized the “hostile attitude of the clergy towards the government and the state,” accusing the clergy of “supporting [territorial] German claims” and for “patronizing of the underground”. Several bishops – by no accident those with the most independent attitude, such as Bishop Stanisław Adamski from Katowice – were accused completely unjustifiably of a “servile attitude towards the Nazi occupant.” The minister of administration, Władysław Wolski, who was the signatory of the declaration, also demanded that the issue of Church administration in the Recovered Territories was to be settled immediately. At the same time, anti-Church demonstrations were organized, many people were arrested and many provocations followed, and various, sometimes far-reaching, declarations of loyalty were forced from rank and file priests.

Wyszyński decided to start talks with the communist party within the Mixed Commission established in July 1949. Several months of work resulted in the reaching of an agreement, signed on 14 April 1950. The Primate forced its signing despite criticism by some bishops and the Vatican distancing itself from it, as he recognized the need for dialogue. The Church accepted quite far-reaching concessions, agreeing to use the language imposed by the authorities: the agreement condemned the “criminal activity of the underground bands” (this is the term used by the rulers to describe the last armed underground structures). Wyszyński also undertook to call for respect for “state law and authority” and “intensification of work on the reconstruction of the country”. In return, he obtained the consent of the authorities to teach religion in the army, hospitals and prisons, the functioning of a private Catholic university (Catholic University of Lublin), and the functioning of religious orders and seminaries. These were unprecedented solutions, impossible in any of the other satellite states.

Primate Wyszyński and the fight for the independence of the Church

The authorities’ real intentions are best evidenced by their actions immediately after signing the agreement. In January 1950, the state took over the giant Catholic charity, Caritas, which ran hundreds of kindergartens, orphanages and nursing homes. A month later, a statement was issued accusing the clergy of “hostility towards People’s Poland,” and on 20 May 1950, the Sejm passed a law on the confiscation of religious and episcopal church property (mainly land estates), which in many cases constituted the main source of income for monasteries. Subsequent letters from the primate and bishops addressed to the communist authorities, in which they tried to straighten out the accusations and point to cases of aggression against the Church, remained unanswered. The government’s propaganda campaign was in full swing, demanding “the appointment of new bishops in the Recovered Territories.” Placing responsibility in this matter on the Episcopate was intended to play it off against the Vatican (faithful to the centuries-old tradition of not removing bishops once appointed), and against a society seeking stability. The government also failed to keep to the agreement, abolishing religion lessons and the other freedoms it had guaranteed.

And yet, despite these tensions, Wyszyński was not imprisoned during the most difficult period of Stalinism. Preparatory actions include the acts of resettlement or internment of individual bishops (in November 1951 – three bishops from Silesia, in December 1952 – Archbishop Eugeniusz Baziak), accusing groups of priests of espionage based on fake charges (the main accused Józef Lelito, was sentenced to death on 27 January 1953; the sentence was changed to life imprisonment). In turn, the decree of the State Council of 9 February 1953 provided that the authorities had the right to approve or reject any Church appointment, which in the long run meant that it was possible to decide almost freely who was to be included as a member of the Polish clergy. Wyszyński objected to this initiative.

The turning point came only after the death of Joseph Stalin on 5 March 1953. As we know from the perspective of 70 years, it brought only a temporary liberalization of the system – three more years had to pass for a thaw to come. Immediately after the death of the dictator, the authorities took over an important Catholic journal, which combined a high intellectual level with full loyalty to the Church: “Tygodnik Powszechny”, whose editors refused to publish a mournful panegyric in honour of the politician. This act of discord sealed the fate of a long-time harassed and marginalized weekly.

The Episcopate under the leadership of Cardinal Wyszyński repeated the gesture of disagreement on a much larger scale in May 1953. Their letter to the authorities, in which they protested against the persecution, is known by the Latin name “Non possumus”, “we do not agree” – from the phrase that appeared in the Acts of the Apostles. By listing the usurpation and injustice of the authorities, they were dotting the i’s and crossing the t’s. The authorities decided to confront them. In mid-September 1953, the trial of Bishop Czesław Kaczmarek and his four associates, accused of creating a “subversive and spy center”, began. They were sentenced within a week, and on 22 September, Kaczmarek was sentenced to 12 years of prison.

Stefan Wyszyński: interrex in handcuffs

Wyszyński was at liberty for four days more. The leader of the nominally Catholic, but in fact split, Pax organization, Bolesław Piasecki, recognized by the communists as an effective negotiator, urged Cardinal Wyszyński to abandon the “Non possumus” policy and agree to the authorities’ February decree, in which they usurped the right to supervise appointments. Wyszyński wrote another letter to the government in which he protested against the trial of Bishop Kaczmarek. In this situation, the communists decided that there was nothing to wait for, the orders had been issued. Listeners of the evening sermon at St. Anna Church, dedicated to the medieval patron of Warsaw, carefully listened to the declaration “Christianity will always call for resistance, and fight every hypocrisy”. Wyszyński was accompanied to his house, located 200 meters further down on Miodowa Street, by a group of the faithful. Later, Wyszyński sent them home.

Two hours later, before midnight, several dozen officers appeared at Miodowa Street. Initially, there was a scuffle, and finally Wyszyński was given a letter with the government’s decision, under which “he was to be immediately removed from Warsaw” and all activities related to his function.

Even in the light of the law of that time (which did not provide for internment), it was an unlawful move; at the same time, it showed that the authorities were reluctant to hold a show trial for Wyszyński. The primate refused to formally acknowledge the letter, stressing that his detention was carried out by force. Several officers packed his things. A little after midnight, a civilian car escorted by the army left Warsaw. In the morning, a column of vehicles reached Rywałd near Toruń. “I was led into a room on the first floor. I was told that this was where I was going to stay, that I shouldn’t look out of the window”- noted Wyszyński on the front pages of his “Prison Notes”. “The bed is not made, personal belongings left behind by a monk who lived here. (…). All the furniture is in ruins: the desk ‘sticks to the wall’, as does the bedside table, a basin with no water, and personal underwear and clothes in the wardrobe. On the floor a pile of books covered with paper. Dirty floor (…)”.

Wyszyński stayed in a cramped cell for just over two weeks. In October 1953, he was sent to a prison within the walls of the former monastery in Stoczek Warmiński, then (in 1954) to the monastery in Prudnik, and finally to Komańcza from where he was released as a result of pressure, protests, thaw and the election of the new leader of the communist party, Władysław Gomułka, 27 October 1956, three years and a month after his imprisonment.

He returned to Warsaw as a true interrex, an authority for millions of Polish Catholics, which he remained up until his death in May 1981. But on that misty autumn morning in Stoczek Warmiński, looking at the broken plaster, the dirty water basin and the patrol carrying weapons in the courtyard, he did not know if he was going to be forgotten, tried or martyred.

Author: Wojciech Stanisławski

Transation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin