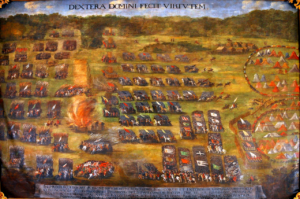

On the night from 6 to 7 October 1620, a seventy-three-year-old Crown Grand Hetman Stanisław Żółkiewski perished on the battlefield in the last act of a drama that had begun a month prior. At the beginning of September, amid growing political tensions between the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire, the Hetman entered Moldavia – an Ottoman tributary to which the Polish Crown had its own claims – to support the incumbent ruler Gaspar Grațiani, in what was intended as a show of force and a way to reinforce Polish political influence in the region. Żółkiewski’s army fortified its position in Țuțora (pol. Cecora), preparing for the arrival of Ottoman and Tatar troops. For the experienced commander, this must have felt like a déjà vu; twenty-five years earlier he had served as a second-in-command in a victorious battle against the Crimean Tatars in the same spot.

by Michał Wasiucionek

This time, however, his plans quickly unraveled: a defeat in battle (18-19 September 1620) collapsed morale and sparked panic among his troops, with many soldiers and Grațiani fleeing the camp. The hetman managed to restore a modicum of order and ordered an organized retreat back towards the Commonwealth. Despite low morale, squabbles among the officers, and constant Tatar attacks, the much-reduced army came within a short distance of the border; however, at that moment, soldiers began to flee on their own and any semblance of order imploded. Żółkiewski, with just a handful of men by his side, perished on the battlefield and his severed head was sent to Istanbul as a trophy. As for the hetman’s remains, his wife, Regina, managed to ransom them from the Tatars and arranged for a burial in Saint Lawrence Church in Żółkiew (ukr. Zhovkva).

The Țuțora campaign was an unmitigated disaster that extended beyond the death of its leader. The Crown army was effectively annihilated, with many officers (including Żółkiewski’s deputy, Stanisław Koniecpolski) taken prisoner. Panic engulfed the Commonwealth, exacerbated by an attempted regicide of King Sigismund III (r. 1588-1632) by a mentally unstable nobleman. Even more ominously, the campaign triggered precisely what it was meant to prevent: a full-scale war against the powerful Ottoman Empire. For young and ambitious Sultan Osman II (r. 1618-1622) an anticipated victory over weakened Poland-Lithuania would serve to reassert sultanic authority that had increasingly slipped towards imperial dignitaries under his predecessors. However, in a striking reversal, the Commonwealth managed to muster resources and fight the Ottomans in the Battle of Hotin (pol. Chocim) that took place from 2 September to 9 October 1621. What was to be easy victory for Osman II turned out – as some Ottoman historians argue – to be a turning point in the history of the empire. The peace agreement merely restored the status quo between the Commonwealth and the Ottomans, but the sultan’s relations were irreparably damaged during the campaign; merely seven months later they would rebel and execute the ruler in what became the first regicide in Ottoman history.

The dramatic story of the shocking defeat of Țuțora and the subsequent improbable victory of Hotin has featured prominently in Polish culture and historical memory since the seventeenth century, and so its protagonists, including Żółkiewski. As Jerzy Besala once remarked, the septuagenarian hetman’s heroic death on the battlefield created a powerful myth that would prove particularly popular in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The arch of defeat and rebirth of Poland-Lithuania without doubt had appeal for those who envisioned a Polish national state after the partitions of late eighteenth century. An eminent nineteenth-century historian, Wacław Sobieski went so far as to draw a comparison between Țuțora and Thermopylae, comparing Żółkiewski to Sparta’s King Leonidas. Żółkiewski’s last moments were commemorated in numerous works of literature and art, including paintings by Jerzy Kossak, Witold Piwnicki or Walery Eljasz Radzikowski. On these paintings, the almost solitary figure of the elderly hetman, bathed in light and surrounded by scores of enemies, is transformed into a larger-than-life figure and a model of Polish patriotism.

However, by its very nature, a myth creates an unreliable lens that only reduces the complexities of historical figures and the realities of the past. In contrast to the uniformly heroic image in Polish historical memory, Żółkiewski had numerous detractors among his contemporaries, who criticized his performance in office, opposed his policies, and did not hesitate to ridicule him personally. While these criticisms have been largely outshone by the hetman’s posthumous myth, they present the hetman in a different light than his nineteenth-century representations. Rather than a quasi-mythical figure of national imagination, he appears to us as a talented commander and shrewd but polarizing politician, with an outlook in line with the worldview of his own time and social class. While undoubtedly strong-willed and talented, his life was at the same time defined by other strong personalities of Poland-Lithuania at this time, most importantly Jan Zamoyski, King Sigismund III and Mikołaj Zebrzydowski. In navigating the political landscape defined by factional loyalties, blurred lines between public and private interests and personal conflicts, Żółkiewski employed his talents to advance both what he saw as the common good of the Commonwealth as well his own interests. He was largely successful in doing so, but in some key instances, he fell short of having his way.

Żółkiewski was born most likely in 1547 in his family estate of Turynka in the Palatinate of Ruthenia, in an established and prominent noble family. His father, also named Stanisław, was at this moment a minor official, but enjoyed prestige among his peers and, even more importantly, familial connections that would boost his and his son’s careers. In order to prepare him for his expected role as a citizen of the Commonwealth, young Stanisław was expected to acquire the social and cultural skills befitting a Polish-Lithuanian nobleman, which included, among other things, a knowledge of Latin, familiarity with classical literature, and a degree of legal expertise, as well as horse-riding and fencing. Finally, and most importantly, he had to master the codes of conduct and rhetoric necessary for participating in often contentious political life of the dietines (pol. sejmiki) and a wider political scene. For the youth from magnate families, this was usually achieved by spending some time at Italian or German universities and foreign courts. In contrast, Żółkiewski attended a school attached to Lwów Catholic cathedral complemented by extensive reading on his own, with a proclivity towards ancient history and military affairs. Thus, while local in scope, Żółkiewski’s education was by no means parochial.

An even more important moment in the future hetman’s intellectual and political formation came in 1566, when he was sent to the royal court under the tutelage of his relative, Jan Zamoyski (1542-1605). The relationship with the latter would in many respects define Żółkiewski’s life. Five years his senior, Zamoyski was a towering figure in the political and cultural landscape of the Polish Crown, a man with extensive intellectual horizons and who at the same time was an ambitious if often ruthless politician. The bond between Żółkiewski and his relative would last until the latter’s death, with profound consequences for the future hetman. In 1573, Żółkiewski would accompany his patron to Paris as part of the Polish-Lithuanian delegation to announce the election of Valois prince Henri (future Henri III) as the king of Poland. During the return journey, Żółkiewski would also visit the Imperial court in Vienna in order to calm the waters stirred by the election of French over Habsburg candidate. In doing so, he also partly made up for his lack of education at foreign courts, common among the Polish-Lithuanian nobles.

Henri III’s reign proved ephemeral, as the king abandoned Poland-Lithuania to claim the French crown less than a year after the coronation; however, his successor, Transylvanian Prince Stefan (István) Bathory, would orchestrate Jan Zamoyski’s meteoric rise to power, granting him the offices of Grand Crown Hetman and Crown Chancellor. In turn, Zamoyski would use his position as the king’s right hand to expand his domains and influence, establishing an extensive political machine to finance Bathory’s wars with Muscovy (1579-1582); he would also support his younger relative. Żółkiewski would command Zamoyski’s cavalry unit during the internal conflict with Gdańsk (1577) and especially during the campaigns against the Muscovite troops in Livonia (1579-1582), serving as a military advisor to his patron. Apart from this, in 1583 he also made an appearance at Zamoyski’s wedding to the king’s niece, Gryzelda, in a somewhat unusual role. During a parade accompanying the festivities, Żółkiewski played the role of Diana, the goddess of hunt, surrounded by nymphs and preceded by several deer.

The following year would embroil Żółkiewski in a major political storm that swept through the Commonwealth. Emboldened by royal favor, Zamoyski decided to settle political scores and ordered the arrest and execution of his adversary, Samuel Zborowski, with Żółkiewski carrying out his patron’s orders. Zborowski’s death scandalized public opinion and at the following diet (sejm), Bathory and Zamoyski faced massive opposition; Żółkiewski’s direct involvement in the affair would also draw the nobility’s ire against him and almost led to a duel with a member of the opposing party. The fallout over the affair would haunt Bathory’s death in 1586 and carry on into the reign of his successor.

It was under Sigismund III (r. 1587-1632) that Żółkiewski’s career really took off, initially due to the constant support of Zamoyski. Although the latter initially wanted to become the king himself, he eventually threw his support behind the Swedish candidate against the Habsburgs. In the following conflict, the chancellor obtained a victory in the battle of Byczyna, taking Habsburg archduke Maximilian captive and effectively securing the throne for Sigismund. During the battle, Żółkiewski distinguished himself by capturing the Habsburg banner, but also suffered a wound to the thigh that would cause him to limp through the rest of his life. The sacrifice paid off, though, as he was quickly promoted to the post of Crown Field Hetman (1588) and became a member of the Senate as the Castellan of Lwów (1590).

While Żółkiewski’s rise through the ranks was largely due to Zamoyski’s influence, their bond would soon become a liability. The relationship between the chancellor and the king was tenuous, as Sigismund III was not inclined to cede the levers of power to the magnate. The relations soon deteriorated and paved the way for open conflict at the sejm of 1592, when Zamoyski accused the monarch of plotting to cede the crown to the Habsburgs. When it became clear that neither would prevail, a modicum of rapprochement was found, but the king continued to chip away the chancellor’s influence by denying him and his allies access to offices and land grants. Żółkiewski, as Zamoyski’s relative and associate, was also under suspicion, but continued his cooperation with his patron and campaigned for him in Ruthenia.

In 1595, Zamoyski made a bold attempt to break the gridlock, benefitting from the Habsburg-Ottoman war to intervene in the principality of Moldavia. An army under his and Żółkiewski’s command entered the principality and installed Ieremia Movilă, a Moldavian boyar and Zamoyski’s client, on the throne. After a short confrontation with Ottoman-Crimean troops at Țuțora, Zamoyski managed to broker an agreement, which secured Movilă’s enthronement. At the same time, Movilă swore a secret oath, in which he recognized himself Polish suzerainty and promised to carry out Moldavia’s incorporation to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. While historians recognize Zamoyski’s skill in achieving his goals without triggering a full-scale war, the chancellor also had personal interests in mind: he hoped that the future annexation of Moldavia would allow him to distribute land and thus satisfy his own supporters, who expected their loyalty to be rewarded. These hopes would be dashed: Zamoyski and Żółkiewski intervened once more in Moldavia to protect Movilă in 1600, but the voyvode flatly refused to make good on his promise. Nonetheless, the relationship between Zamoyski, Żółkiewski and the Movilă family would remain crucial in the following decades, eventually setting the stage for the second battle of Țuțora and the hetman’s death.

Żółkiewski’s activities during this period extended beyond Moldavia; as the Crown Field Hetman, he was responsible for pacifying the 1596 Cossack revolt in the Ukraine. Although he argued for a moderate approach and after several weeks of fighting managed to negotiate the surrender with the Cossack leader, Severyn Nalivajko, a riot broke out that resulted in massacre that Żółkiewski was unable to contain. The guarantees of Nalivajko’s safety were also subsequently broken and the rebel commander was publicly executed in Warsaw later that year. While it brought a modicum of order to the Ukraine, the Cossack issue was by no means resolved in the following decades, despite Żółkiewski’s urging to find a more durable solution.

In 1602, Żółkiewski accompanied Zamoyski on the campaign to Livonia against the Swedes, but the following years were dominated by the chancellor’s deteriorating health and approaching death. In the last years of his life, Zamoyski still remained one of the most influential figures in the Commonwealth and his strained relationship with the monarch made him a prospective leader of opposition, while his authority allowed him to keep his supporters together. However, the death of the chancellor triggered a struggle for leadership within the faction that pitted Żółkiewski against another of the late magnate’s allies, Mikołaj Zebrzydowski. The latter took a radical stance against the king and his actions would plunge the Commonwealth into the civil war, known as rokosz of Sandomierz (1606-1608). In contrast, Żółkiewski opposed direct confrontation, eventually siding with the king and acting as one of the commanders in the battle of Guzów (6 July 1607) that would determine the outcome of the revolt. At the same time, however, he would continue to advocate compromise and reconciliation between the two camps.

Żółkiewski’s conciliatory stance won him no friends and he would become a target of ridicule and derision by Zebrzydowski’s supporters, while at the same time failing to dispel Sigismund’s doubts regarding his loyalty. While awarded with the office of the Palatine of Kyjiv, his hopes for becoming Crown Great Hetman were dashed; the post – vacant after Zamoyski’s death – would remain unfilled until 1618. At the same time, Żółkiewski – in his capacity as the Field Hetman – would be responsible for military command in the Polish Crown.

The office of Hetman, while extremely important and influential, was at the same time a difficult and frequently thankless task. The inefficient fiscal apparatus meant that soldiers’ pay was frequently in arrears and the commander was forced to reach to his own pocket to avoid mutiny. Moreover, the number of royal troops was too small to carry out its duties, forcing Żółkiewski to rely on private armies employed by magnates. Since they were under no obligation to obey the Hetman’s commands, assembling and deploying a military force required considerable diplomatic skill and constant charm campaigns to hold the army together. In this sense, warfare was the extension of politics rather than the other way around. Although Żółkiewski was undoubtedly a superior military leader than Zamoyski, in this respect he seems to fall short. Unlike his mentor, whose social and diplomatic talents were widely recognized, Żółkiewski’s irascible and mercurial character frequently put a strain on his relations with other political figures and soured his moments of triumph. His heavy-handed approach and inability to compromise and find a middle ground would also indirectly lead to his tragic death.

In 1610, Żółkiewski reached the peak of his military glory. The death of Tsar Boris Godunov in 1605 plunged Muscovy into turmoil, fueled by numerous pretenders claiming right to the throne with the support of Sweden or individual Polish-Lithuanian magnates. The ensuing chaos encourage Sigismund III to launch a military intervention in the east. Despite Żółkiewski’s insistence on a swift campaign that would capture Moscow and install Prince Władysław on the throne, the army was bogged down by the siege of Smolensk for several months; at the same time, an influential Potocki family began to undermine the hetman’s position at the helm of the army, leading to constant squabbles within the camp. Eventually, the king agreed to send Żółkiewski, along with several thousand men, towards Moscow and against the Swedish-Muscovite army under Tsar Vasilii Shujski. Acting with extraordinary energy, Żółkiewski surprised the enemy and in the battle of Klushino (4 July 1610) annihilated Shujski’s utterly destroying the army almost five times the size of his troops and managed to take the tsar himself as a captive. Emboldened by the victory, he marched on Moscow and negotiated a treaty that recognized Prince Władysław as the new tsar (after his conversion to Orthodoxy) and left a manned the Kremlin with Polish troops. This was an extraordinary success for Żółkiewski, both militarily and politically.

However, the hetman would soon see his success unravel. Disregarding Żółkiewski’s urgings, Sigismund III refused to send his son to Moscow and instead demanded his own election to the Muscovite throne and territorial cessions to Poland-Lithuania. The monarch also failed to grant the hetman the Grand Hetman position that Żółkiewski coveted. Historians remain split on the relative merits of either option: it may be argued that sending adolescent Vladislav to a distant capital with no guarantees of his safety was not the most prudent course of action in king’s eyes. Nonetheless, Sigismund’s refusal to honor the treaty was a major disappointment for Żółkiewski, who resigned his command on the Muscovite front and returned to Ruthenia. There he composed an account entitled The Beginning and Conduct of the Muscovite War, which told his part of the story and critically assessed the policies of the king and his advisers.

The last decade of Żółkiewski’s life was largely defined by the events in Moldavia, where a succession dispute emerged within the Movilă dynasty following the death of Ieremia in 1606. His son, Constantin, faced considerable opposition among the local elite, which opted for a rival branch of the family. In November 1611, the Ottomans took advantage of the conflict to put their candidate on the throne. Ousted, Constantin Movilă and his mother fled to Hotin and appealed to the Commonwealth for help in recapturing the throne. The removal of Movilă was not only a political, but also a familial issue in Poland-Lithuania. Most importantly, Constantin was brother-in-law of Stefan Potocki, a member of an influential magnate family that had Sigismund III ear. Indebted to them, the king allowed Potocki to intervene in the principality and put a contingent of royal troops under his command. However, the campaign launched in summer 1612 proved a total failure: the army was defeat at Cornul lui Sas, Potocki was taken captive and Constantin perished while fleeing the battlefield. Żółkiewski did not come to Potocki’s help, but later that year negotiated a treaty with the Moldavian voyvode.

Żółkiewski’s attitude has been praised by historians, who juxtaposed his responsible handling against Potocki’s adventurism, arguing that Poland-Lithuania was in position to go to war against the Sublime Porte. However, for many contemporaries, Żółkiewski’s motives were not so lofty. At the sejm of 1613 many alleged that Żółkiewski had his own axe to grind; the Potockis were his main political rivals and had sought to undermine his position at the court. Moreover, Żółkiewski had his own candidate for the Moldavian throne, Gavril Movilă, from a rival branch of the family; thus, the failure of Potocki’s expedition would weaken his adversaries and pave the way for his own designs in the principality. These allegations seem justified: already in 1611, Żółkiewski collaborated with Moldavian opposition to challenge the Potockis’ influence.

This pattern repeated itself in 1615-1616, when two other in-laws of Movilă, Princes Samuel Korecki and Michał Wiśniowiecki, launched another attempt to restore Ieremia’s descendants to power in Moldavia. Although their private campaign was initially successful, Żółkiewski not only failed to support them, but actively prevented them from replenishing their troops and provisions. For many observers, this amounted to deliberate sabotage, driven by private interests rather than the reason of state. At the same time, Żółkiewski dispatched Gavril Movilă along with his client and experienced diplomat, Samuel Otwinowski, to lobby in Gavril’s favor at the Porte. They were unsuccessful in this respect, but Żółkiewski’s obstruction succeeded in derailing Korecki’s efforts: in August 1616, his much-diminished army was forced to surrender and Korecki along with the Movilă family fell into Ottoman captivity. Żółkiewski opted to negotiate another treaty with the Moldavian voyvode and the Ottomans.

The political fallout was massive and the public opinion turned against Żółkiewski. At the sejm of 1616, he faced accusations of senility, incompetence and privileging his private interests over the Commonwealth’s good. His response to the accusations did not dispel doubts regarding his motives, since he argued in favor of Gavril’s claim to the Moldavian throne and it seems that factional interests of the magnate played a role in his decisions. After all, Potocki, Korecki and Wiśniowiecki were his adversaries in Poland-Lithuania; their failure certainly played into his own hands. This does not mean that his appeals to the common good were but a smokescreen; instead, in the political culture of the seventeenth-century nobility private and private interests were deeply entangled and often indistinguishable from one another.

However, the Moldavian campaigns permanently tarnished the hetman’s reputation. Eulogized following Klushino, in the last years of his life he was mercilessly ridiculed and widely considered unfit for duty. In turn, Korecki, who managed to stage a daring escape from Ottoman captivity and returned to Poland-Lithuania, became a popular hero for the nobility. Żółkiewski’s declining reputation had serious consequences for his ability to carry out his military duties that manifested soon. In 1618, a campaign against Tatar raiders ended in an embarrassing defeat, when commanders refused to follow Żółkiewski’s orders and join his camp. This debacle drew a new wave of criticism against the octogenarian magnate accused of incompetence and senility. Żółkiewski’s only consolation were the long-coveted posts of Crown Grand Hetman and Chancellor that Sigismund III finally granted him the same year. Thus, he achieved the same official position as his friend and mentor, Jan Zamoyski. However, their position was very different in real terms. For Zamoyski, the appointment greatly extended his influence and served as a building bloc in a growing political machine; in turn, Żółkiewski achieved this position when his political career was in decline: suffering from failing health and widespread concerns whether he was fit for office anymore.

From this point of view, the Țuțora campaign appears in a somewhat different light. While the tensions between Poland-Lithuania and the Ottoman Empire were undoubtedly growing, personal and factional motives cannot be discounted. On the one hand, Żółkiewski desperately needed a win that would restore some of his political prestige and control over the army; a demonstration of force in Moldavia would serve not only to entrench the Commonwealth’s influence in the region, but also help the hetman reassert the control over his army. In this respect, the 1620 campaign was intimately tied to the previous interventions in the principality, conducted by his adversaries. However, the scarcity of royal troops meant that in doing so, he had to rely on private units provided by the very people he alienated during the past decade, such as Samuel Korecki. Combined with tactical mistakes and political miscalculation, this created a perfect storm that led to Żółkiewski’s heroic death and the virtual annihilation of his army.

Historical accounts often abound in moral and political judgements that seek to identify true statesmen and condemn self-serving careerists. Thanks to Żółkiewski’s achievements and his dramatic death on the battlefield, his portrayal has been overwhelmingly heroic, while his adversaries were relegated to the latter camp. However, looking beyond the eulogizing narratives, we find a more fleshed-out image of a skilled military commander and ambitious political figure, trying to achieve his goals in line with the political culture of his time.

Author: Michał Wasiucionek