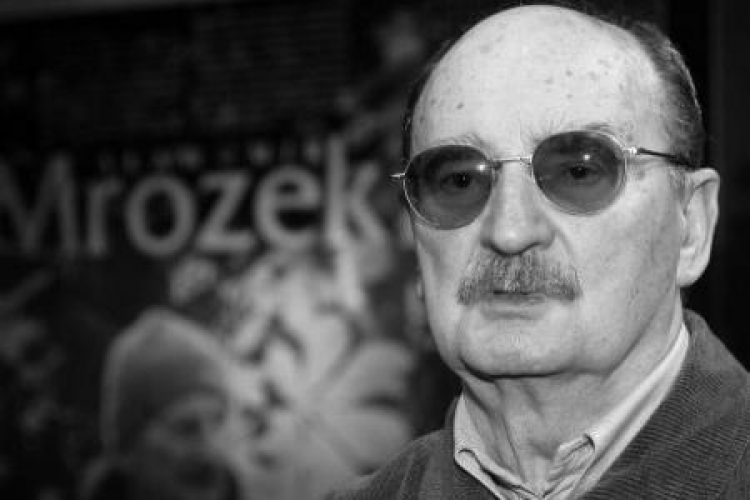

His prose was more difficult to translate than the poetry of the most hermetic poets, because he referred to the fabric of wit, of local absurdities and peculiarities. Despite this, he hit the stages around the world, becoming one of the most famous Polish writers of the 20th century. Bitter, ironic, and ruthless to himself – [this was] Sławomir Mrożek.

by Wojciech Stanisławski

In encyclopedic entries that list his numerous achievements, Mrożek is defined not only with such honorable titles as “playwright,” “essayist,” and “cartoonist,” but also as “satirist.” It has always met with my objection, I had a sense of a deep mismatch between the term and Mrożek’s actual achievements. In communist Poland, a “satirist” was usually a person who was treated with disgust and pity. He was forced to remain silent about disregard for the law and the oppressive authorities, due to the rigorous censorship and state monopoly on publishing. Instead, he repeatedly condemned social vices – as this was not being censored – namely, the laziness of bureaucrats, the rudeness of waiters, indecency, dossing around and bigotry, and with time, when the financial situation of Poles improved, he added road hogs. Such “satirists” who could not tell whether they are writers or the vanguard of the propaganda front, often after a while could not bear life’s pain [any longer] and drank themselves to death. Unless, [of course], they were protected by a layer of self-admiration which proved to be stronger – then they lived comfortably until the end of their days. Mrożek had nothing to do with such practices.

He made his debut twice. For the first time in 1950, as a 20-year-old reporter of propaganda, at the height of Stalinism. It was a feature article titled “Young City”, devoted to the builders of Nowa Huta, a communist metallurgical plant on the outskirts of Krakow. His propaganda article, full of pathos, was never re-published, but not because Mrożek, like many writers years later, denied having been devoted to communism – either by totally silencing this fact, or in 1956, during the so-called political thaw, by making a ritual apology. No. Mrożek’s account of his commitment to communism, which he made years later in his autobiography Baltazar, is perhaps the most honest and the most ruthless in Polish literature. Simply put, the feature article, although it enjoyed several weeks of publicity and gave the twenty-year-old a job in the newspaper, in retrospect, is no different from any other popular feature article at the time. Bombastic, written in a melodic way, it was perfectly impersonal. “Between two banks – 1949 and 1955 – a huge bridge was already spread with six arches: a great construction of a six-year plan” – these words could be written by almost any young talented person.

“This text was a masterpiece of bad writing, or writing the untruth.” – Mrożek did justice to himself after more than half a century. “I walked around trying to gain the reporter’s eye. I stared at the volunteer workers, from the Service of Poland, digging ditches, undressed to their waist – as the weather was dreamlike – wearing faded, identical side caps and identical wide pants. But I didn’t see anything interesting or special about them. (…) With some relief I returned to Krakow with the same truck (…) And yet a few days later I wrote my article and was delighted with how talented I was. I wrote it on the basis of a total, symmetrical inversion of what I didn’t like the most, to what I supposedly liked. And the amazing thing is that I wrote this without a bit of cynicism.”

This is not the end of vivisection. “Many years later,” wrote Mrożek in the same essay, “I was watching TV when I was already in exile. It was the historical screening of the film by Leni Riefenstahl about Hitler in his pre-war time, in honor of whom the Parteitag was organized in Nuremberg. Suddenly I was all ears and discovered distant echoes of that time. Volunteer workers, not soldiers yet, but young people, in sports T-shirts, were marching obediently, unarmed, holding shovels though. A solemn and serious mood on the eve of events of extreme importance, but for now, silence, hush. It reminded me of something. The unbearable pomposity of it all was ridiculous and repulsive.”

In this way, Mrożek settled his past commitment many years later. Thus he took part in the vivid and controversial discussion that continues to this day – whether a fascination with Marxism and Isaiah Berlin’s concept of “historical inevitability” were crucial for people to enter the communist party.

There was not – said Mrożek – a fascination with Hegel. There was a fascination with power, inevitability – and at the same time a complex combination of ambition, self-admiration and a dream of growing out of post-war muddy soil.

Mrożek debuted for the second time three years later – the volume of short stories Practical Half-Armour saw the light of day in 1953. Probably the climax of the action of the title story earned Mrożek the label of “satirist” from subsequent authors of textbooks and encyclopedists. The story was a seemingly cheerful satire on the deficiencies of centrally controlled trade, with no interest in anything like real demand, without any conscience of phenomena such as advertising or market research. A transport from the Central Headquarters appears in the large city store – a transport of half-armor – a steel element of armor indispensable to 17th-century hussars who want to protect themselves from an arrow or a lance aimed at their chest, but perfectly unnecessary to anyone three hundred years later. Salesmen are in trouble – the goods sent by the Central Headquarters must be sold! The story has, however, a happy ending. By appealing to snobbery and parsimony, an absurdity occurs:: armor becomes “fashionable” and thus is sold in the blink of an eye.

23-year-old Mrożek probably had not heard of surrealists or dadaists – but the concept on which the whole story was built, i.e. the box of armor appearing in the gray and empty clothing store of the mid-1950s, has the power of Marcel Duchamp’s first ready-mades. Several other stories in the same volume in a similarly passionate way show the pure, unrestricted absurdity of human existence, the incompatibility of behavior, words and styles to real situations. The book was popular among readers, especially since a few years after Practical Half-Armor had been published, there were already a dozen Mrożek stories, novels and plays. It is actually funny and ambiguous that different readers were amused with something different while reading the books. Polish readers, who had neither the opportunity (censorship!) nor patience to read the analysis appearing in the West, indicating an elementary lack of rationality in the social or economic life of real socialism, perceived in the writer’s stories and plays a suggestion of this state of affairs. The suggestion was clear enough so that the particularly vivid absurdities of everyday life used to be referred to for many years by the phrase “It’s like Mrożek”.

Critics and theatre directors in countries on the other side of the Iron Curtain have associated Mrożek’s work with “absurd theater,” juxtaposing him with Ionesco, Beckett or Topor – and staging his plays on the same stages. “Tango” enjoyed the greatest success, already two years after its publication in Poland (1964) it was staged by the Royal Shakespeare Company, and performed on the world’s largest theater stages and festivals over the next several decades. In Poland, he co-created colloquial language, and his name became popular, while around the world he was valued as an avant-garde writer describing new experiences.

Everyone is born with natural talent and it is impossible to derive Mrożek’s aesthetics and philosophy from his own or “historical background”. However, one can think for a moment about how he experienced the dramas of history as a child. He was born 90 years ago in a farming village in the Małopolska region, to a family of peasants and clerks divided by origin and aspirations. The sons of such families usually gravitated towards universities, editorial offices and publishers of Krakow several dozen kilometers away. The most important Polish theater play of the 20th century, “The Wedding” by Stanisław Wyspiański from 1901, is about such a clash. In one room, at a family celebration of lords (frock coat, binoculars) and peasants (“sukmana” – the traditional coat of peasants, peacock feather attached to a hat). People of these two social backgrounds became part of Mrożek’s imagination, and, half a century later, they became absurd figures of the procession he described.

Mrożek himself, however, did not become part of the “Wedding” panorama. The Second World War broke out at the end of his childhood, when the order of hierarchies was inverted. This transformation continued after 1945, when the new authorities in Poland decided, according to the doctrine, to forcefully industrialize the country and change its social structure. Mrożek in Kraków in the late 1940s, from a broken home due to the early death of his mother, helpless against the misery caused by the war, was, colloquially speaking, “available”. And it was no accident that he was invited to write a report on the great construction of socialism in Nowa Huta.

Mrożek’s inquisitiveness and distance saved him from being involved in the system – as well as from many other things. Reflecting on his work and way of life a few years after his death, it is easier to notice how much distance he kept towards his achievements, how he questioned all attempts at creating narratives about him as if he was a hero. Personal distance is one thing – many people value him, which does not prevent them from showing off in articles and interviews. Mrożek, with his restraint, allusions and reluctance to share anecdotes from his life, was a torment for journalists, biographers and enthusiastic participants of social life. He was silent at banquets, he discussed some of his tough family experiences only in the above-mentioned autobiography; about other things he never said a word. The several-phrases long “Open Letter”, published on 28 August 1968, in which Mrożek protested against the aggression of the Warsaw Pact forces against Czechoslovakia was the shortest of all the statements published at that time by Polish intellectuals who had contact with the media in the free world:

“I am a Polish writer, not an emigrant, a member of the Polish Writers’ Union. In view of the active participation of the Government of the Polish People’s Republic’s armed aggression against the Czech Socialist People’s Republic and the military occupation of that country, I declare as follows: I protest against this action. I am in solidarity with all Czechs and Slovaks who oppose this action. Especially with my comrades, Czech and Slovak writers who are persecuted and imprisoned.”

No great words, no references to great cultural texts, no emphasis on the role of his own “I”. These six sentences (for which Mrożek was banned, moreover, for several years to enter Poland and his plays, including “Tango” were not staged in Poland or any other countries of the socialist camp) were just like most of his declarations in public matters: modest but firm. One would say – a stereotypical gunslinger, not an intellectual. He valued “cowboy virtues”, much like Leopold Tyrmand, another emigrant from the People’s Republic of Poland with whom Mrożek was friends and carried on a correspondence for many years. “He died as if struck by a bullet in the heart, just as sheriffs used to die in good old American Western films,” he wrote in 1985, in a obituary on Tyrmand.

He also preserved the unusual, seemingly ambivalent attitude of “modest pride” commenting in interviews, that he gave only rarely, on his work that had grown over the years. He was never witnessed to be narcissist, celebrating his work or justifying his youthful commitments. He declared himself a “craftsman”, doing his job as neatly and accurately as possible. This independence and modesty allowed him to equally accept his works from various shelves, from hermetic dramas to cartoons with a single punch line. “The scale of his creative possibilities, unheard of, was difficult to comprehend,” as has been often emphasized by his friend and researcher from Krakow, Prof. Tadeusz Nyczek. “Because there we have drawings that he remained faithful to for the longest time; and grotesquely philosophizing prose, (…); and dramas, the most famous part of the oeuvre; and film scripts, two of which he made himself as a director; and essay and journalism of the highest quality again, and even such trivialities, literary toys, like ‘Donosy’, famous during martial law, later published in London in 1983. In contrast, in 2004 Mrożek revealed himself as an epistolographer. (…) Everything together makes for a truly extraordinary portrait of Mrożek himself. It is not even a matter of fact that Mrożek is able to write an excellent analytical essay on Ashes and Diamonds as well as a philosophical comedy about three starving men on a raft. It’s about an internal act of courage, the lordly gesture of a free creator: here you are, I can do it – I can sign with my own name the most serious and the most trivial works.”

Author: Wojciech Stanisławski

Transation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin