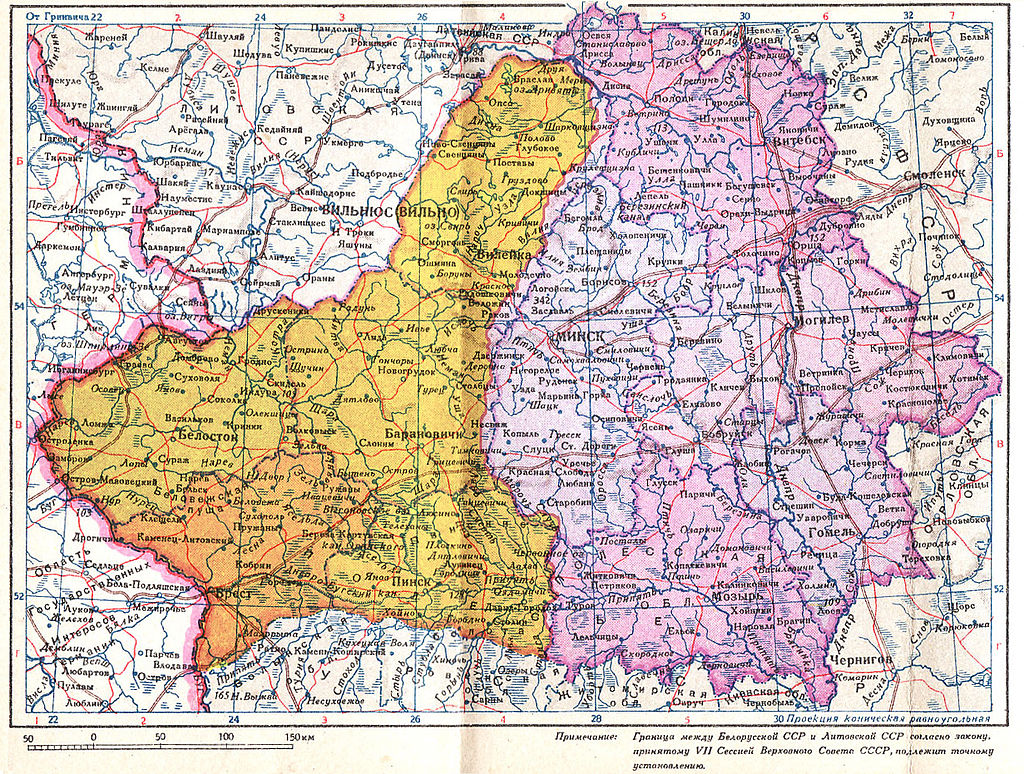

On 1 September 1939, the attack of Nazi Germany on Poland marked the beginning of the Second World War. After 16 days, the armies of the USSR, which was, at that time, an ally of the Third Reich, also crossed the Polish border. One consequence of these actions was the division of the territories of the Second Polish Republic between the Stalinist Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. From the Belarusians’ point of view, this meant the annulment of the unfortunate provisions of the Riga Peace Treaty of 1921. Under the terms of this Treaty, ethnic Belarusian territories were divided between Poland and the USSR/BSSR (Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic), and any hopes of granting independence to the Belarusian People’s Republic proclaimed in 1918, were dashed. Paradoxically, the unification of the Belarusian nation took place within the borders of an enormous ‘concentration camp’. After all, it was from September 1939 onwards that mass repressions, human rights violations on a gigantic scale, and the persecution of those with different official views, became the norm in the life of the Belarusians.

by Aliaksandr Smalianchuk

The ambiguity of these events, and the impossibility of conducting unfettered historical research at least until the mid-1990s, significantly complicated and hindered the process of the scientific and social reworking of the meaning of September 1939, as well as its impact on the fate of the Belarusians. This task remains relevant to this very day.

Soviet blended meanings

The discussion on the significance of the events of 1939, held in Belarus on an annual basis in September, is one of the manifestations of the contemporary ‘war for memory’. Memory, which is one of the most important tools for creating social networks, as well as collective and individual identity, has become an important element in the fight for the country’s future. In a situation where Alexander Lukashenko’s regime is attempting to copy and revive Soviet ‘ideological blends’ and replace the authentic history of Belarus with them, a growing number of citizens are beginning to understand that the state is imposing on them a vision of the past which, in reality, their ancestors never shared. As a result, the official historical policy in Belarus is opposed by historians who are not linked to state institutions.

So what was September 1939 really about, and what were its consequences for Belarus?

In the era of the BSSR and the USSR, the answer was clear: ‘The dreams of the Belarus working masses have finally come true. Thanks to the far-sighted policy of the Communist Party and the Soviet authorities, the Belarusian people were united for the first time within a single free, sovereign, Soviet state.’ 17 September, the day when hostilities began on Belarusian territories, was included in the national holidays of the BSSR as the day of the country’s unification.

History according to Novik

The Soviet vision of the events of that time is mentioned again in contemporary history textbooks. In the textbook for grade 11, published in Russian, Professor Yevgeny Novik points out the ‘peaceful policy of the USSR’, the efforts of France and Great Britain to redirect the German aggression to the East, their reluctance towards Moscow’s proposal for creating a collective security system in Europe, and the nature of German-Soviet relations in August 1939, forced by the prevailing circumstances. The signing of the secret protocol to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was, in Novik’s opinion, also forced, but the author avoids discussing the negative consequences of its signing.

Prof. Novik explains the aggression of the Red Army against Poland (presented as a ‘liberation offensive’) by the Soviet government’s concern for the ‘people of Western Belarus’. The author emphasises that the offensive was launched only after German forces had occupied the territory of ‘ethnic Poland’, and assures that the ‘majority of the population of Western Belarus greeted Soviet soldiers with flowers, bread and salt, and with tears of joy’, while the ‘majority of Polish soldiers and officers surrendered without a battle’. The author mentions the Katyn Massacre, but, as it appears, only to emphasise the impossibility of identifying the perpetrators of this crime.

Prof. Novik emphasises that, in the autumn of 1939, the ‘dreams of the Belarusian nation about living in a single Belarusian state came true’. This is how the BSSR is described in contemporary studies and propaganda as a sovereign nation-state. In the textbook discussed, there are no references to the repressions or unpopular social and economic changes of those years.

In the 21st century, however, it is becoming increasingly difficult to defend a similarly simplistic point of view, even with the residue of Soviet mentality in the state ideology and historical policy of the Republic of Belarus, as well as in the face of the state’s aversion to pluralism. In recent decades, the lack of any enthusiasm accompanying the anniversary of the ‘unification’ has been particularly conspicuous. This could still be observed in 2019, when the official media practically ignored the anniversary of 17 September 1939, without dedicating any radio or television programme to it. One can consider this an expression of either indifference or confusion on the part of ideologues.

17 September discussed anew

However, the situation changed markedly in the autumn of 2020. The wave of protests brought about by the falsification of the presidential elections of August 2020, and the subsequent repressions carried out by the militia and the army of the Ministry of the Interior, forced ideologues to rapidly define the ‘external enemy’ of Belarus. The choice was Poland, which resulted in a propaganda offensive. An important component of the ‘enemy’s image’ was to refresh the image of the ‘Polish – and a master’s – oppression’ by referring to the Soviet vision and interpretation of the events of autumn 1939. There was even a proposal to celebrate 17 September as the ‘Day of Unification of Belarus’. In March this year, the anti-Polish propaganda campaign was completed with repressions against the activists of the Union of Poles in Belarus, and headmasters of Polish schools, as well as retaliations against Polish diplomats.

At the same time, among Belarusian cultural and social elites in opposition to the Lukashenko regime, a discussion is underway on the assessment and interpretation of the events of autumn 1939. Many members of the elite still consider 17 September a ‘national holiday’, and believe that the unification under Stalin had a positive meaning, because it allowed Belarus to recover from the Polish (!) and Soviet repressions of the 1920s and 1930s, and to preserve its cultural identity. This is how these events are assessed, for example, by historians of the Belarusian Historical Society in Białystok. The well-known columnist Vitaly Cygankov, in his broadcast on Radio Svoboda, even appealed to Belarusians to follow the example of Lithuania, whose elites were mostly critical of the German and Soviet policies in the late 1930s, whilst simultaneously welcoming Stalin’s decision to hand over Vilnius to Lithuania in the autumn of 1939.

Such a position, however, means refraining from any moral assessment of the actions of the Soviet leadership, in particular the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, and Soviet aggression against Poland. Meanwhile, contemporary changes require the rethinking of many 20th-century events, especially the situation of 1939, and the policy of the ‘first Soviets’ in Western Belarus. It is worth bearing human values in mind, and assessing the fate of Belarus within the context of European and world history.

Burnt lands

Perhaps, first of all, it is worth noting that, in September 1939, Belarus became party to a war that proved to be the most terrible in its history. Belarus became the arena of struggle between two totalitarian powers. Similar arguments appear in the works of such historians as Leonid Lycz, Anatol Trafimczyk, or Rygor Lazko. At least some of the Belarusian elites realise what price Belarus paid for the ‘unification’. The afore-mentioned protocol de facto initiated the Second World War. It is also worth remembering that the military aggression of the USSR was accompanied by an ideological offensive. Meanwhile, the Second Polish Republic, left by the allies to it own devices, stood no chance against the armies of the two totalitarian states, which sealed their victory with a friendship agreement between the USSR and the Third Reich, concluded on 28 September 1939.

Oral history records can play an important role in the reflection of Belarusian society on the events of autumn 1939 and their consequences, allowing, incidentally, also those who are generally deprived of the right to speak, to become familiar with unknown accounts, as well as to evaluate the past in the perspective of universal values. Oral history, as we know, refers to individual life experiences, to the store of memory of a particular person. It has developed its own methodology, within which the method of collecting, storing and analysing interviews has been specified. The resources of oral history make it possible to construct new visions of the past, or to complement or correct existing ones.

At this point, I would like to refer to the recollections gathered by associates and volunteers of the Belarusian Oral History Archive [www.nashapamiac.org], participants of the project titled ‘1939 in the memory of Belarusian residents’. The project brought together the recollections of respondents living on both sides of and near the ‘Riga border’ (i.e. the Polish-Soviet border in 1921–1939). The broader aim of this study was to reconstruct the communicative memory (in the meaning of Jan Assmann’s term) of a community that had only sporadic contact with Soviet history textbooks, and kept its distance from official interpretations of the past.

Research within the scope of this project was conducted in 2012–2014 in the regions of Gomel, Brest, Minsk and Vitebsk. A total of about 200 interviews were conducted; respondents were predominantly people of rural origin, born between 1920 and 1930. Most had an incomplete primary education obtained at a ‘Polish’ school, or had completed the first few grades of a Soviet school. The vast majority of respondents were women, who had left their native villages only in rare cases, most of them of Orthodox faith. The method of autobiographical narration was consistently used in the research.

The stories of the elderly

Clearly outlined in their recollections, is the hope of the Belarusians for ‘changes for the better’, which were to take place as a consequence of the appearance of ‘Soviet power’ in the place of Polish power. These hopes were influenced by the stories of the older generation, often those who had moved to the Roman Empire, fleeing the 1915 front during the First World War, recalling the prosperous pre-war and pre-revolutionary Russia, and the Orthodox Russians providing assistance to them on the territory of Russia proper. The nightmare of the Stalinist regime, with its mass repressions, gulags, executions, and brutal coercion of collectivisation, were usually considered to be lies of Polish propaganda.

A characteristic feature of almost all collected accounts is the disillusionment of the Belarusians with the ‘new authorities’. The very first actions of the Soviet authorities, which accepted the plundering of landed estates, and encouraged violence against foresters, landowners, Polish settlers, and officials, prompted many of those interviewed to keep their distance. The fact that the murderers of the landowner Roman Skirmunt (7 October 1939), who had enjoyed a grand reputation in the area, had gone unpunished, is particularly noteworthy among the inhabitants of the village of Porzecze.

The theme of repression and violence appeared in almost all of the recollections. The respondents drew attention to the fear and feelings of helplessness in the face of the new authorities, whose modus operandi was violence and spreading propaganda.

The distance towards the new authorities is also visible at the level of expressions used by respondents towards them. Only occasionally do terms such as ‘our’ or ‘their’ appear. The general terms are ‘Russians’, ‘Bolsheviks’, or ‘first Soviets’. The authorities who took over the territories in 1944, following the expulsion of the German occupiers, are usually referred to as the ‘second Soviets’.

They were here only briefly…

Attempts of researchers at coaxing the respondents to compare the ‘first Soviets’ with the Polish authorities, or with the ‘second Soviets’, sometimes provoked ironic reactions: one of the most frequent was the statement that the ‘first Soviets’ were better, because they were here for a short time, they came in 1939 and left already in 1941’.

Almost none of the interviewed inhabitants mentioned the ceremonial rallies or public meetings organised after the entry of the Red Army. This could be explained by the fact that they had been held in places where there had previously been clandestine cells of the Communist Party of Western Belarus in the Second Polish Republic: meanwhile, Polish intelligence and police attempted to preclude their existence in the border areas. Moreover, the proximity of the border and lively contacts with Belarusians ‘from behind the cordon’ had led the inhabitants to doubt the advantages of the ‘Soviet paradise’, in contrast to Belarusians living further from the border.

Many people took the retention of the ‘old border’ badly. Despite the official decision on the unification of Western Belarus with the BSSR of 14 November 1939, the old border continued to be controlled by uniformed services: travelling to Minsk from Grodno or Brest (or vice versa) required applying to the authorities for a special pass.

The gathered recollections prove that, already in 1940, hopes were alive among the Belarusians that the rule of the ‘first Soviets’ was only a temporary phenomenon. At that time, Polish rule began to be perceived more favourably, and many hoped for its return. However, in the summer of 1941, instead of Polish landowners, the German occupation administration appeared.

The results of the research indicate that, for the direct witnesses to history living west of the Polish-Soviet border, September 1939 became a symbol of disillusionment with the new authorities: the ‘first Soviets’ did not become ‘ours’. Even today, the respondents’ fear of repression and their dissatisfaction with the changes of 1939–1940 are palpable. The latter can also be seen in relation to newcomers from the eastern part of Belarus, i.e. Belarusians from the USSR, often referred to as ‘hungry kolkhoz workers’. Also significant in these recollections is the almost complete absence of distinctions of a national character: the ‘social’ point of view dominates, classifying others on the basis of (sometimes speculatively assessed) ‘class affiliation’.

The rise of new attitudes of ‘local’ Belarusians towards Soviet power, consisting of disappointment, incomprehension, and finally hostility, can also be traced on the basis of archival documents. So far, however, ‘official historians’ have failed to show any professional interest in studying these phenomena, and ‘social historians’ are often unable to obtain permission to conduct queries. In Belarus, there restrictions are still in place on access to documents collected in state archives, while documents of the State Security Committee (KGB) and the Ministry of the Interior, are inaccessible to all researchers.

Two sites of memory

As a result, one may conclude that, in the memory of contemporary Belarus, September 1939 is not one but two ‘sites of memory’, and very distant at that. One is the memory of the symbolic triumph of the Belarusians: the BSSR authorities and the Communist Party are credited with its emergence and consolidation. It is still present in historical policy and state ideology, it dominates in textbooks and, if the current system of power is preserved, it may affect social consciousness with increasing force. The second ‘site of memory’ functions at the level of communicative memory, is a symbol of tragedy, refers to the vision of man helpless in the face of a cruel and merciless power, and remains a source of social trauma, which still cannot be the subject of dialogue and treatment.

What does the presence of these two images of one sequence of historical events in Belarusian society indicate? Likely the fact that the division of Belarus, symbolised by the ‘Riga border’, is still functioning today, rooted in the relics of Soviet ideology. This in turn means that the problem of the ‘unification’ of Belarus still remains a task and challenge to be addressed. Except the contemporary ‘Riga border’ no longer runs through fields and forests, but through memory and conscience.

Author: Aliaksandr Smalianchuk, PhD and Doctor Habilitatus, is a historian, currently a visiting professor at the Centre for Belarusian Studies of the Centre for East European Studies. Author of five books and dozens of articles mainly on national relations in Belarus and Lithuania in the 19th and 20th centuries, and collective and cultural memory. Editor-in-chief of the Homo Historicus yearbook (Minsk). A former employee of Grodno University and the European Humanities University in Vilnius, currently employed at the Institute of Slavic Studies of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki