He was not born Polish, but became a Pole by choice. Rudolf Weigl was a pioneer in using lice to breed typhus germs and the creator of the first effective vaccine against this terrible disease.

by Piotr Abryszeński

Rudolf Weigl was born in Moravia to an Austrian family on 2 September 1883. After his father’s premature death, his mother remarried a Pole, high school professor Józef Trojnar. It was his stepfather who instilled him with a passion for Polish tradition and culture.

In 1907, he graduated from the University of Lwów. During the First World War, he was drafted into the army, where he attempted to make an effective vaccine against typhus – a disease more terrifying than the enemy bullets that had already killed millions of people. Weigl’s work was successful – a very highly effective vaccine was made. After Poland regained independence, in 1920, he became a professor at his alma mater despite his relatively young age. He lacked formal medical education (his doctoral and postdoctoral thesis concerned issues in zoology and histology), however, he decided to found the Research Institute of Epidemic Typhus and Viruses in Lwów where he continued his research. It was at the institute that an innovative method of using insect intestines for vaccine incubation was developed. This laid the foundations for the concept of modern virus breeding.

The fame of this Lwów scholar quickly spread around the world. Weigl’s invention was used on a larger scale among Belgian missionaries in China, saving thousands of Chinese, for which he was honored with the highest decorations, including the Papal Order of Saint Gregory the Great. Scientists from many different countries came to Lwów to learn about the Institute’s methods.

In 1939, Weigl stayed in Abyssinia, where he studied the local epidemiological situation, but due to the threat of war, decided to return to Poland. The war broke out and in September that year Lwów fell under Soviet occupation. The occupiers were aware of the importance of Weigl’s invention, and therefore he was given additional rooms for the research. Shortly after the occupation of Lwów by the German army in the summer of 1941, General Fritz Katzmann from the Waffen-SS appeared in Weigl’s office with a proposal to sign the Volkslist and move to Berlin. As a scholar, and a son of two Austrians, this seemed the perfect solution. But being aware of the consequences, Weigl only answered briefly: “You choose your homeland only once. I chose mine in 1918.”

However, his work was valuable and the Germans knew it perfectly well. They only responded with a withdrawal of support for his candidacy for the Nobel Prize in 1942.

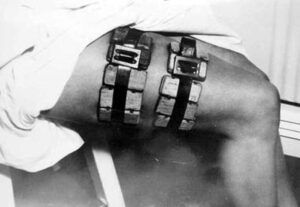

What was the phenomenon of Rudolf Weigl’s invention? He invented a special technique of feeding lice, which consisted in attaching special cages on the feeder’s body through which the lice could suck human blood. Cages were placed in hidden places, most often on the thighs or on lower parts of legs, to hide unsightly wounds. After about 45 minutes of feeding, the cages were closed to prevent the lice bursting from overeating. Then they were injected with typhus germs. When they multiplied, the lice were prepared under the microscope. Their intestines were the basis of the vaccine. Due to the permanent marks left by their bites, only men were employed as “feeders” before the war. It was only after the outbreak of the Second World War that nobody was bothered about it any longer. At that time, the vaccine was needed by the occupying armies, thus Weigl’s laboratory had to be expanded. It was the only known and effective method of fighting this terrible disease at the time.

Those who were employed as “feeders” at the Institute increased their chances of survival and such documents were usually considered as “sure ones” by the Germans. For this reason, the Institute employed representatives of the Polish intelligentsia, scientists and people of culture, as well as members of the independence underground. The Lwów “feeders” included, among others, brilliant mathematician Stefan Banach, microbiologist Ludwik Fleck, poet Zbigniew Herbert, geographer Alfred Jahn, geneticist Wacław Szybalski and many others. Employment at the Weigl Institute could bring freedom in the event of a round-up, it also gave an additional food allowance, which gave the starving representatives of Lwów’s intelligentsia a chance to survive the occupation. It is estimated that about two thousand people worked for the institute.

The activities of the Institute were not limited only to the production of a vaccine at the behest of the occupying armies. Due to difficulties in recording the obtained vaccines and medications, they were sent, as part of a strict conspiracy to concentration camps, Jewish ghettos and soldiers of the underground.

Faced with the advancing of the Soviet army, Rudolf Weigl made the dramatic decision to leave Lwów. In 1944 he moved to Krakow, and then, after a few years, to Poznań, where he continued work on the vaccine. As a result of groundless accusations of collaboration with Germany, the communist authorities blocked the award of the Nobel Prize in 1948. He posed new research questions, had new ideas, but in the post-war reality he did not obtain adequate funds to expand his activities. He died on 11 August 1957 in Zakopane.

Author: Piotr Abryszeński – PhD, employee of the History Research Office of Institute of National Remembrance

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin