Cardinal Wyszyński returned from prison to Warsaw on 28 October 1956. ‘Polish October’ was underway – a few weeks of one of the most important political shifts in Poland’s post-war history. He immediately began talks with the new authorities, which resulted in the signing of what was called a Small Agreement on the last day of that year. It restored the legal status from the 1940s, abolishing, inter alia, the decree on the manning of church posts.

by Rafał Łatka

Call for unity

The chief concern of the Primate after his return from prison was the deepening of faith in the nation, and a call for public unity. The teachings of Archbishop Wyszyński were addressed to all social and professional groups, and especially cared for the young. A significant gesture was his maintaining the Bishops Michał Klepacz and Zygmunt Choromański as collaborators, who, during his imprisonment, had demonstrated submissiveness towards the communist authorities. At the same time, however, he dismissed several clergymen who had grossly exceeded their authority.

A year after ‘Polish October’, it was already clear that the thaw was coming to an end, and the authorities of the Polish People’s Republic were intensifying the faith-related state policy, wanting to weaken the Church. The Primate was aware that the goal of those in power was the atheisation of Polish society, but he did not avoid dialogue with the authorities. At the beginning of January 1958, he met with Władysław Gomułka, the First Secretary of the Party. Their difficult talks took place four more times, and their atmosphere systematically deteriorated.

The period of the normalisation of relations between the state and the Church was very brief. Already in July 1958, police officers attacked the monastery at Jasna Góra. This was followed by a campaign to remove crosses and religion classes from schools. In the following years, the policy of selective repression and limiting the presence of the Church in the public sphere continued.

The Great Novena and celebrating the millennium of Poland’s baptism

On 3 May 1957, Cardinal Wyszyński initiated a pastoral programme for the renewal of spiritual life in Poland, known as the ‘Great Novena of the Millennium of Poland’s Baptism’. Particular emphasis was placed on deepening the faith and the moral renewal of the nation after the devastation caused by the war, the policies of the communist regime, and the lack of national sovereignty.

Each year of the Great Novena had a specific theme. In their sermons, priests called for the deepening of faith, the defence of unborn life, the renewal of marriage and family, the responsible education of young people, the preservation of ‘love and social justice’, the fight against national vices, and the acquisition of social virtues. The programme was based on deepened Marian piety, with the Jasna Góra sanctuary the centre of its implementation. From the Cardinal’s perspective, the two planes mentioned above (the struggle for Poland’s Catholic character and the defence against secularisation) complemented and pervaded one another.

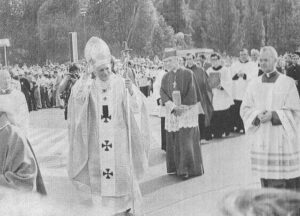

The dispute with the authorities over the vision of Poland culminated in the years 1965–1966: this was the time of the pre-planned celebrations of the Millennium of Poland’s Baptism. Cardinal Wyszyński inaugurated the millennial celebrations with a mass celebrated at the Gniezno Cathedral on 1 January 1966. During another religious event that took place at Jasna Góra at the beginning of May, in the name of the Polish Church, he made an ‘act of consecration of Poland for the next 1,000 years into the maternal captivity of Mary, Mother of the Church’.

With these pledges, the Episcopate wished not only to strengthen the Catholic faith and morals of the nation, but also to guarantee the freedom of the universal Church. The celebrations covered not only the entire country, but also Polish communities around the globe. The Primate officially invited the Holy Father to take part in the millennial celebrations of the Polish Church in Poland, but the highest state authorities did not consent to the Pope’s arrival. Despite the sabotage of the celebrations by state authorities, the Church won the propaganda competition with the communist state, which attempted to oppose the official celebrations of the Millennium of Poland’s Baptism. The authority of the Primate became unquestionable in Polish society.

Seismograph of shocks

The Primate reacted to all major socio-political events in the Polish People’s Republic. Following student protests in March 1968, together with the Episcopate, he spoke out in defence of students who were imprisoned and expelled from universities. At the same time, he pointed out that the anti-Semitic campaign initiated by the authorities would contribute to the deterioration of the image of Poles in the West, speaking of a ‘monstrous shadow […] of renewed racism’ in the context of the communists’ actions.

In December 1970, when protests of workers on Poland’s Baltic coast broke out, the Primate also demonstrated empathy towards social discontent. At the same time, he decided to postpone for later the reading of the Episcopate’s letter on the ‘biological threat to the nation’ (containing a harsh assessment of the demographic policy of the authorities), not wanting to destabilise the situation in the country. In the face of communist violence, he believed that the Church should take the side of the persecuted society. ‘The Church must stick more with the beaten than with those who have taken hold of the authorities, and are trying to camouflage their guilt. […] This is blood, and it is consecrated blood,’ he said during a meeting of the Episcopate.

Sleepy decade

When Edward Gierek was in power, Cardinal Wyszyński strengthened his emphasis on expanding social rights and freedoms, far beyond the demands for religious freedom. During a meeting of the General Episcopal Council of 26 January 1971, the Primate clearly stressed: ‘As bishops, we must, on the basis of the pastoral means available to us, save the freedom of the Nation and the Church. Much will depend on how we conduct our affairs. Society is distrustful and reserved towards changes. We bishops cannot give in to emotions. We must […] act very prudently so as not to give a pretext for claims […] that the Episcopate’s intransigence has contributed to the intervention. We are children of this nation and concern for the nation, for its security and integrity, is not alien to us.’

The Primate believed that the Church should seek to expand social freedom, especially within the sphere of religious rights, and to increase its influence on social policy. He was aware that most Poles agreed with him on this issue. On 18 November 1972, during a meeting with Paul VI, he stressed that the Church in Poland could be defended effectively only by relying on the nation. He also emphasised in his notes the close relationship between the Church and the Nation.

In late 1975, the Primate criticised the content of the amendments to the Constitution of the Polish People’s Republic drawn up by the communist authorities. On his initiative, the Polish Episcopate prepared two memoranda containing the critical stance of the bishops on the amendments to the Constitution. The authorities withdrew from some of the proposed amendments: the resistance of various milieus was successful.

In June 1976, when protests broke out in the Warsaw district of Ursus, and the town of Radom, following a rise in food prices, the Episcopate intervened in defence of workers repressed for their participation in strikes. Cardinal Wyszyński kept his distance from the democratic opposition emerging at that time, fearing that the Church would become entangled in the politics of the Polish People’s Republic: ‘Our actions must be thoughtful, mature and calm. We cannot align ourselves ad pari with one or another secular institution or political centre. Lay people can do so differently to bishops,’ he stressed. However, he repeatedly defended those repressed by the authorities.

The Pope’s visit and Solidarity: late fruit

On 6 October, following the untimely death of Pope John Paul I, the Primate went to Rome for yet another conclave. The election of Cardinal Karol Wojtyła as Pope, which took place on 16 October 1978, was of great significance for the Primate. One of his closest collaborators was elected – the Metropolitan of Krakow, his likely successor as Primate, with whom he’d had friendly relations in the 1970s. Shortly after the conclave, he wrote: ‘The election of a Pole to the See of Peter is perhaps of global dimension; through the mysterious death of two popes Poland, so strongly criticised by various countries (France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany), became the hope of the Catholic countries.’ The newly elected Pope emphasised his relationship with the Primate and singled him out during the cardinals’ homage by accepting his standing.

Cardinal Wyszyński played a key role in negotiations with the authorities, and preparations for the Pope’svisit to Poland, which took place in the first ten days of June 1979. ‘The presence of the Pope in a country of the [Eastern] Bloc marks a type of crack in the Iron Curtain,’ the Primate wrote. And indeed: that curtain was just beginning to break down. This was manifested, inter alia, by the revival of religious life throughout Central and Eastern Europe.

When workers’ strikes broke out in Poland in the summer of 1980, the Primate took a twin-track approach: he called for calming the situation (in fear of a Soviet intervention) and, at the same time, he supported the strikers’ most important demand: the establishment of independent trade unions. The communist authorities broadcast manipulated fragments of his sermon in the media on 26 August 1980, creating the impression that the Primate had distanced himself from the protests. Therefore, the following day, together with the General Council of the Episcopate, Wyszyński issued a statement supporting the social demands of the strikers.

He retained a friendly attitude towards Solidarity, if somewhat distanced. He stressed that the creation of an independent social movement relieved the Church of many of its political duties towards the totalitarian authorities. At the same time, he was always afraid of the threat of a Soviet intervention, and postulated solid ‘grassroots work’. He hoped that trade unionists would refer to Catholic social teaching. Once again, he played a serious political role by supporting the cause of the creation of the Independent Self-Governing Trade Union Solidarity of Individual Farmers in 1981. The farmers’ unions, having no ‘weapon’ in the form of a strike, were in a much worse position than the ‘urban’ unions: without the Primate’s support, they likely would not have been registered.

The Primate had been seriously ill since 1977, and the final relapse of his illness in April 1981 had already prevented his active functioning. On 12 May 1981, he celebrated his last Holy Mass. In the following days, he asked that prayers in his intention be offered to the Pope, who had been seriously injured in the attack on St Peter’s Square in Rome. He himself passed away on 28 May at the Palace of the Archbishops of Warsaw at Miodowa Street. His funeral, attended by several hundred thousand people, was a great demonstration of the attachment of the Polish society of the time to the Church.

The personality and leadership talents of Cardinal Wyszyński were of great importance for saving the independence of the Church in Poland from the communist authorities. Thanks to the pastoral schemes prepared and conducted by him, the faith and attachment of Poles to the Church deepened. He also contributed to an increase in independent attitudes, and ones opposing the communist authorities, which grew significantly in the 1970s, their most important expression being the creation of the social movement known as Solidarity.

Author: Rafał Łatka – Historical Research Office of the Institute of National Remembrance

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki