After Poland regained independence in 1918, it was of great importance to gain recognition and international visibility as a modern state. In this matter nothing is as convincing as circulating images across the world of new investments and flourishing cities with crowds of happy young people on the streets. That’s one of the many reasons why the Polish government paid so much attention to urbanization, particularly in the border areas where the provisions of Treaty of Versailles were constantly being questioned by neighboring states. Soon, some of the cities became showcases of Poland’s drive towards modernization with rational urban planning and avant-garde architecture, yet they remained very individual and different from each other, which is still visible nowadays.

by Alicja Gzowska

The most noticeable case of a city built from scratch is Gdynia – this former fishing village became one of most important Baltic ports and home to more than 120 000 inhabitants in less than two decades. Getting access to the sea was a significant opportunity for Poland, but in 1920 on 140 kilometers of shore there was no Polish harbor. The nearest one – located in the Free City of Gdańsk (Danzig) – was dominated by Germans. It is no wonder that the development of Gdynia, Poland’s “gateway to the world”, became even more crucial with the construction of military and commercial port. Since then harbor and city expanded and competed over conveniently located areas, especially in the center. Their growth took place at such a rapid pace, that the municipality found it difficult to control and balance private initiatives with communal needs and representation. The successful fusion of these elements can be experienced in the heart of the city, where the northern part with the port basins is treated as a part of the city center, and the west-east axis of 10 Lutego Street leads from the railway station to the shore. Eventually it opens up to a longitudinal square framed by prominent modernistic buildings and ends up as a broad pier cutting into the sea. This manner of addressing the connection of the city to the sea distinguishes Gdynia among other European harbor cities.

Despite some bold planning decisions, Gdynia never became a monumental demonstration of the power of the reborn state. Instead, it turned into unique conglomerate of various districts with complementary functions such as residential, industrial, and holiday resorts. Accelerated development was regulated only by some general rules regarding urban layout, land use, density, greenery, volume and height of buildings. Soon, as this framework has been gradually filled up, Gdynia became famous for its human-friendly scale and modern, yet diverse, architecture.

But it wasn’t like this in the beginning. In the early 1920s, investors preferred more traditional architecture with strong allusions to historical forms considered “typically Polish” such as arcades, column porches or decorative tops of buildings. As the city grew, and the influence of modernist architecture flowing into the city from young designers was strengthening, it became more and more obvious that traditional architecture simply did not suit the place. What really reflected the prosperity of thriving Gdynia was the strict simplicity of its bold bright modernist buildings. This can be seen in the case of numerous luxurious tenement houses (especially on Świętojańska Street) in which the elegance of architectural form and its representative values were emphasized by the building’s details, for example the stone cladding on the facades and the expensive finishing of staircases. Reinforced concrete and brick were used for their construction to conveniently fit spacious sunny apartments and commercial premises, but also to reach six floors – the highest number allowed in the city center. As some of them have rounded corners and balconies, round windows, masts and thin railings on roof-terraces, they were often compared to ships that had been moored in the city. Sometimes, in order to emphasize the dynamics of the building, the ground floor was covered in a dark color, so it appeared almost to be floating – as it is in the case of the Zakład Ubezpieczeń Społecznych (Social Insurance Institution) building. Also, impressive modern urban villas were erected by individuals from Gdynia’s elite circles, who preferred calmer and more intimate locations in the garden-city district of Kamienna Góra with convenient access to city beach and marina or in Grabówek – a district inhabited mainly by high-ranking military personnel. But in the city – not only on the outskirts, but also in the center – there are also modest housing estates for officials and workers with, simple, comfortable and affordable flats.

Two sophisticated engineering constructions may be considered Gdynia landmarks: the Marine Station, possessing an internal courtyard covered with a thin shell concrete dome, and Market Hall built with huge parabolic steel girders and reinforced concrete frames. They correspond well with other local innovative industrial architecture such as a rice mill, a port cooler, an oil mill, and a grain elevator.

Dynamic development of the city and its expressive character soon became a topic for advertising publications, magazines, radio programs and films. Postcards juxtaposing photos of the same places “before” and “after” became very popular, underlining the “miracle” of the industrialization of the country following the example of Pomerania.

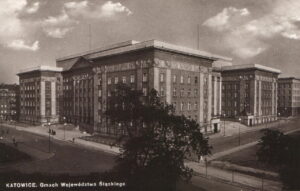

Indeed Gdynia, the “facade of Poland”, was tightly linked by the coal trade to the “black heart” of the country – Upper Silesia, and particularly with the city of Katowice. This former German town became part of Poland only in 1921, has a rather short history dating back to the middle of the 19th century. Similarly to Gdynia, it was located very close to the border, so its newly constructed buildings were expected to differ significantly from the older German ones (that meant for instance avoiding references to the Gothic and Neo-gothic style) to shape a new image of a modern Polish city. This was the case of the seat of the Silesian Parliament and the Cathedral of Christ the King – monumental edifices drawing on simplified (modernized) academic classicism. However, what determines the architectural image of the city are not public buildings, but its dense, tall modernist housing.

Katowice was declared the capital of the autonomous province of Silesia, which meant that it was populated quickly not only with miners and workers, but also with a growing number of clerks, civil servants and other representatives of the middle class (the number of inhabitants grew from 56,000 in 1922 to 135,000 in 1939). And although mines and ironworks were the source of city’s wealth, their large areas and location very close to the city center restrained development to a large extent. Similarly, this well-connected city was cut in half by railroad tracks, which determined its growth in the south. To meet the demand for housing and at the same time make the best use of the limited number of plots in the city center, the tallest possible buildings, mainly tenement houses, were erected. Assistance in this matter came from local iron producers, who sought new markets for their products, also in the construction industry. That is why the house of the professors of the local technical high school built in Katowice became the first skyscraper in Poland. Its steel frame construction enabled it to reach a now not-so-impressive height of 8 stories, but its completion in 1931 was widely celebrated as a great success. The building was the protagonist of numerous publications, and even a short, widely distributed, movie promoting iron constructions. But what is more important, it paved the way for an impressive seventeen-story (fourteen above the ground) skyscraper located at 15 Żwirki i Wigury Street. It was built for the Polish Revenue Office and its employees, meaning offices were located in the lower part of the building, while the high tower was designed for comfortable flats.

What is also interesting is that the structural engineer responsible for its design – Stefan Bryła had earlier spent several years traveling over the world and working on the construction sites of high-rises in in New York and Chicago. This fact did not escape journalists’ attention who soon claimed that Katowice is “the most American of Polish cities”. Indeed, life in this city was at a very high level. Due to the autonomous character of the province all revenues were distributed on site, allowing for intensive investment in infrastructure: extensive plumbing, gas and power networks, asphalting of streets, and public transportation. But it was not only basic benefits: for example, there were 9 cinemas in the city, a modern airport in Muchowiec was put into use in 1926 and, a year later, Polish Radio Katowice began operating.

The city of Stalowa Wola is slightly different case – it was built from scratch like Gdynia and closely linked to industry like Katowice. But unlike those other cities, Stalowa Wola was located almost in the geographical center of Poland – far from the borders. Such a position was considered the best possible location for building the Central Industrial Region (COP) next to Gdynia – the largest Polish investment in the interwar period – dedicated to the production of armaments. The investor, the Ministry of Military Affairs, aimed to build an industrial agglomeration on a scale of the Soviet city of Magnitogorsk in the place previously occupied by the vast expanses of pine forest. The construction of the city and steelworks began in March 1937, however, the city was not finished, as works were interrupted by the outbreak of war. It is estimated that about 25% of the city plans were realized, that is: Southern Industrial Plants, a power plant and a small part of housing in southern part of the city. This means that Stalowa Wola has never obtained its planned representative city center.

However, the city’s military character is evident at every turn, as the space has clear demarcations derived from a hierarchical system. The city layout is a skillful fusion of the structure of a military camp with its safety rules and a “garden-city”, a popular concept combining the advantages of urban and rural life. Living in the greenery, at least 1.5 km from the industrial plants, brought citizens not only comfort, but also provided security and camouflage in case of an enemy attack. The four completed housing complexes are called the Workers’, Mayors’, Officers’ and Director’s Colonies, and architecture and the standard of equipment of each reflects the status of the residents. The idea of a garden-city was most easily visible among the modern, yet at the same time subtly classical, villas of the highest rank of the military, but also repetitive modernist blocks and functionalist semi-detached houses were placed at a distance from each other, perpendicular to the main street, and additionally separated with green belts isolating them from traffic noise. Flats were not large, but they always consisted of several rooms, a kitchen and a bathroom – a standard that was difficult to find even in much larger cities.

The simple forms of the buildings in Stalowa Wola, although similar to those in Gdynia and Katowice, are distinguished by their decorativeness. This applies to both their forms, where the geometric shapes are juxtaposed to break the uniformity of pure shapes, as well as to geometric ornamentation in an Art Deco style. Modest facades have been varied by adding pilasters and arcades supported by pillars, and even grids of mullions in windows add up to a rhythmic decoration. One very characteristic element of Stalowa Wola’s buildings is the cladding made of dark brown clinker brick: they cover the foundations of houses, the frames of doors and windows, the pillars of arcades, among many others, and all of them protecting walls against moisture and dirt on the plaster. This dark clinker covers also the most representative building that became the symbol of the city – the Steelworks General Office. Its rich facades are formed with breaks, faults and arcades as well as diverse windows and balcony loggias. The main entrance is placed in the corner and marked with a modernist clock. What is particularly interesting is its luxurious art deco interior preserved in the original condition until today.

In 1938, the authorities gave the city the name Stalowa Wola (“steel will”) as an expression of recognition for the “steel will of the Polish nation to stand out for modernity”. Thus, in a symbolic way, they included it in the state propaganda program, that aimed to promote the image of a Poland as a powerful country, drawing strength from rapid and consistent modernization. Since architecture was among the most important tools of this program, a great deal of attention was devoted to the aesthetics of the developing cities. Despite the strong influence of modernism, which perfectly reflected the spirit of modernity, but was often criticized for its transnational character, Polish cities on their paths toward modernization were able to develop individual characteristics. The three examples discussed above show briefly how different processes influenced their image in a fascinating way that is still visible today.

Author: Alicja Gzowska

Transation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin