As soon as Poland regained independence, it became an advocate of creating a Ukrainian state. Piłsudski championed the idea of a federation according to which Lithuania and Belarus were to be linked to Poland on the territory of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. According to that concept, Ukraine was to be a sovereign state, with Symon Petliura as its leader.

by Piotr Bejrowski

For a free Ukraine

On the wave of social processes occurring in the 19th-century Europe, the ‘self-determination’ and crystallisation of the Ukrainian nation also began – primarily in opposition to Russia. The national revival was largely linked to the repressive policy of the Tsarist regime. Saint Petersburg treated the ‘Ruthenians’ inhabiting the south-western territories of the Russian Empire were as a local faction of the Russian nation.

Meanwhile, new political organisations were formed, whose members – ‘Ukrainians’, as they began to call themselves in opposition to the vision pushed by the Russians – aspired to the role of a modern European nation. The relatively liberal policy of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, where social and cultural activities and the Ukrainian language flourished, offered an opportunity to emphasise their own distinctiveness.

The First World War coming to an end and the Tsar’s fall provided an opportunity to fulfil the dream of having one’s own state. This meant not only a conflict with Russia engulfed in revolutionary chaos, but also with the Poles, who for decades had been fighting to regain the independence lost at the end of the 18th century and to recreate the Polish state within its pre-partition borders.

In the years 1918–1920, Ukraine, unlike Poland, could not count on support from the Western countries. The reborn Polish state, on the verge of independence, faced a mortal threat – a Bolshevik invasion. Poland saw an opportunity in supporting the Ukrainian aspirations, and Józef Piłsudski became one of the proponents of creating a free Ukrainian state. He believed in a future alliance against a common enemy – Russia.

The Ukrainian Central Council, established after the February Revolution, proclaimed the independence of the Ukrainian People’s Republic (UPR) in Kyiv as early as November 1917, and just a month later the Bolsheviks established the puppet Ukrainian People’s Republic of Soviets and occupied Kyiv. They soon withdrew from the city, and under the Treaty of Brest were forced to recognise the independence of the UPR. After the German capitulation, the Bolsheviks declared the treaty invalid and challenged the aspirations of the Ukrainians. Conflict was inevitable.

To Kyiv

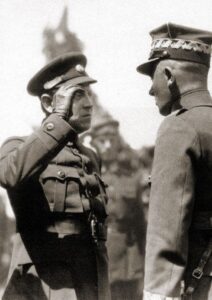

Ukrainians argued about the extent to which Piłsudski’s vision was acceptable to them. A partner for the Polish side turned out to be Symon Petliura, Chairman of the UPR Directorate and Commander-in-Chief of the country’s army. It became clear to both sides that the territorial borders of Poland and Ukraine had to be delineated, so as to jointly face the Bolshevik threat.

Piłsudski and Petliura were certainly unanimous about one thing – the greatest threat to Poland and Ukraine was Russia. Neither of them believed in the possibility of a peaceful settlement of the dispute with the unpredictable Bolsheviks, nor in the possibility of an agreement with the leaders of ‘white’ Russia. Piłsudski’s aim was to geopolitically secure the stability of the Polish borders by creating a federation of states from Estonia to the Dnieper. This was because he was aware that Poland would not be able to stand alone against Russia – whether ruled by the Bolsheviks or the ‘Whites’ – and Germany defeated in the war. Piłsudski and Petliura entered into a military as well as a political alliance: Poland recognised the independence of the UPR and pledged to assist it in its confrontation with the Bolshevik army. The Ukrainians renounced their rights to eastern Galicia.

Launched in April 1919, the Kyiv expedition became an attempt to fulfil this vision. The basic military premise of the plan was to smash the Bolsheviks in Ukraine. However, the Bolsheviks were retreating and no major battle took place, so the strategic goal of the operation was not achieved. Instead, they managed to take Kyiv and install the government of the UPR there. At the same time, despite difficulties in equipping their own troops, the Poles gave the Ukrainians tens of thousands of weapons, hundreds of thousands of rounds of ammunition, uniforms and heavy equipment. On 4 May 1920, the combined armies entered Kyiv.

The response of the local population was weaker than expected. Tired of successive armies marching through their territory since 1914, it reacted apathetically to the appearance of yet new troops. At the beginning of the Kyiv offensive, the Polish army numbered 60,000 soldiers, and the Ukrainian army 4,000. The military forces of the UPR were steadily increasing, but the Bolshevik offensive meant that they did not play a major role in combat. It is possible that this passivity had a decisive influence on the fate of Ukraine.

Some commentators and political opponents accused Petliura of not having a realistic view on things and criticised his pro-Polish orientation. These same opponents, however, were prepared to ally themselves with Moscow rather than Warsaw. From today’s perspective, one can appreciate Petlura’s political pragmatism and far-reaching perception of his nation’s interests.

Vinnytsia on the Boh River

One of the events that gave hope for peaceful coexistence between Poles and Ukrainians and closer cooperation in the face of the threat from the Red Army was the meeting in Vinnytsia (Winnica) in mid-May 1920. In the presence of members of the Ukrainian National Council and numerous representatives of the local Ukrainian, Polish and Jewish population, Piłsudski said: ‘(…) in our shining bayonets and sabres you should not see a new imposition of someone else’s will. I want you to see in them a glimmer of your freedom (…). I will be happy when it is not I, the humble servant of my people, but the representatives of the Polish and Ukrainian Sejm [i.e. parliament] who establish a common platform for understanding. Hear my call on behalf of Poland: Long live free Ukraine!’

Soon, however, the Bolsheviks were able to consolidate their forces and launch a successful offensive westwards. After relatively bloody battles, the Polish and Ukrainian forces had to withdraw in June 1920. The events of August, when the decisive battle took place on the outskirts of Warsaw, were decisive for the fate of the entire war. As a result of a successful counter-offensive in autumn of the same year, the enemy forces were successfully repelled. The Polish army, exhausted by the devastating war, finally stopped the attack on the Zbruch River line. However, they continued to provide financial and military support to the Ukrainian People’s Republic fighting against the Red Army, transferring supplies and uniforms and sending a support force of 1,200 soldiers to the Ukrainian army, which already numbered around 40,000. Poland, which itself could not count on support from the West, finally agreed to sign the peace treaty in Riga in March 1921. However, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic gained international recognition, and the UPR Directorate passed a resolution to continue its activities in exile – initially in Poland, and later in Prague and Paris.

Symon Petliura was assassinated in the French capital in May 1926 by Sholem Schwarzbard. The motive for the crime was the pogroms that were to be suffered by his family in Ukraine under the Directorate. It is likely, however, that the assassin was acting under the inspiration of Soviet services. Perhaps it was no coincidence that the assassination took place just after Piłsudski took power following the May 1926 Coup. The decision-makers in Moscow must have been interested in preventing a renewal of the Polish-Ukrainian alliance. For several decades, Soviet propaganda skilfully used a number of myths and misrepresentations aimed at conjuring up a black legend of Petliura. Fortunately, the memory he deserves is slowly being restored today.

Author: Piotr Bejrowski

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki