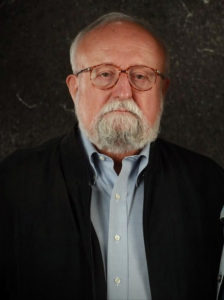

“I am mostly scared of the moment when I feel that I have planted all the trees or I have written all the pieces, but I am far from this – I still have plans,” he stated on his 80th birthday. Krzysztof Penderecki, one of the world’s greatest contemporary composers, died on 29 March at the age of 86. Over his lifetime he had written over 100 pieces and planted over 4000 trees. But, as he said, he was still making plans for the next 20 years.

by Łukasz Starowieyski

It is enough to browse the internet to notice how Penderecki was filed energy and new ideas almost till his last days – concerts, festivals, and creative work plans. “He is unable to take a rest, it tires him too much,” his wife, Elizabeth, used to say.

First notes

He is said to have written his first pieces at the age of 8, although they were likely drafts to practice the violin. However, Penderecki had been exposed to music since early childhood. “My first contact with music, apart from listening to my father playing the violin, was listening to the brass band from Dębica. I dragged my nanny along with me to listen.” His parents also sent him to piano lessons. However, he got along with neither the instrument nor the teacher and he quickly abandoned the attempt. The breakthrough came when his father gave him the violin. Young Krzysztof practiced every day, both before school and in the evenings. Most often, Penderecki played Johann Sebastian Bach.

The town of Dębica, where he was born on 23 November 1933, soon became too small for him. In the 1950s, he studied at the State Higher School of Music (now the Academy of Music) in Krakow. Penderecki took composition lessons first from Franciszek Skołyszewski, and then later from Artur Malawski. After graduating in 1958, he became an assistant in the Composition Department.

The road to fame

The following year Penderecki took part in a competition arranged by the Polish Composers’ Union and submitted three compositions. When assessing the pieces, the commission did not know the names of the composers. When they awarded the three prizes, after unsealing the envelopes containing the names of the winners, it turned out that there was only one name within them…an almost unknown 25-year-old named Krzysztof Penderecki. The commission was outsmarted because each piece was written in a different handwriting. “I decided – to be sure of the prize – to send three different compositions. I’m ambidextrous, so I wrote one score with my right hand, the other with my left, and I gave the third to a colleague to rewrite.” He received awards for Strophes (Strofy), Psalms of David (Psalmy Dawida) and Emanations (Emanacje).

Strophes, based on Greek, Latin and Hebrew texts, and written for a soprano, a reciting voice and 10 instruments, qualified for the Warsaw Autumn festival. Although it received contradictory reviews. “Penderecki’s reading of antiquity is thoroughly revealing, [and] contemporary” – wrote one of the critics, and another asked: “Is there no humor, energy, fun, variety, surprise nor adventure in the world of music?”

Threnody – leading the vanguard

The appearance of the piece at the Warsaw Autumn festival was a ticket to global salons. The score was released by the German publisher Herman Moeck, and soon the piece began to be performed all over Europe. All the while, Penderecki did not let up the pace. A year later, he wrote one of his most famous pieces 8’37″ (named for the length of the composition), later changing its name to Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima (Tren Ofiarom Hiroszimy). This composition earned him the UNESCO Tribune Internationale des Compositeurs award in Paris and was played by radio stations around the world. It was then that he was first recognized as the world’s leading representative of the musical avant-garde. This title was confirmed by his subsequent pieces, Fluorescences (Fluorescencje) (which features saws and typewriters in addition to traditional instruments, ) and Passion According to St. Luke (Pasja według św. Łukasza) .

His works aroused not only controversy, but also often caused rebellions by musicians. Some conductors refused to conduct Threnody, and scheduled performances in Rome or Cologne were significantly delayed. The audience did not always receive his music with applause either. “Each ‘booo’ gave me motivation. To this day, it gives me pleasure that someone is outraged by my music. (…) Still I achieved everything I wanted to achieve.”

In the 1970s, he stood behind the conductor’s stand. The adventure began accidentally. According to the score of a piece that he composed – Actions For Free Jazz Orchestra, the piece was to be performed without a conductor. However, it turned out that the musicians did not manage and Penderecki decided to conduct. It turned out to be a hit. “While conducting my own works, I can aim at bringing individual elements of the composition to the perfect image of the work in my imagination (…) it is only myself who knows how the course of my work should be shaped in time.”

In the following years, he led the largest orchestras in the world – primarily conducting his own works.

Hollywood and Dali

Penderecki’s fame went far beyond the circle of contemporary music lovers or of the avant-garde. It reached, among other places, Hollywood. “[Stanley] Kubrick called me once and asked if I could write music for his new film. I was busy composing an opera at the time and gave him some tips. I advised him which of my pieces he should listen to,” said Penderecki. His music played an important role in one of Kubrick’s most famous films, The Shining. His works were also used in films by other famous directors: William Friedkin in the Exorcist, Dawid Lynch in Wild at Heart and Twin Peaks, Martin Scorsese in Shutter Island, as well as Andrzej Wajda in Katyn. In general – despite many suggestions – he avoided film music. “After all, I am a so-called classical music composer. If someone wants to use my pieces, I give permission, but I would not write music for movies. It is servile music and one has to do what the director wants him to do and one has to write according to the motion picture. I’m not interested in musical illustration.” He gave in only once – he wrote the music to The Saragossa Manuscript by Wojciech Hass.

He did collaborate with famous jazz and rock musicians though. In 2005, he even recorded an album with [Radiohead guitarist] Jonny Greenwood who thus described the allure of Penderecki’s work: “Using traditional composing methods, he was able to create a whole new world of sounds. I didn’t even suspect that it could have been composed that way! I began to hunt for Penderecki’s scores and under their influence I completely changed approaches to the issue of scale and time in music.”

He did not succeed in a joint project with Salvador Dali. “We were talking with Salvador about a joint project called Creation of the World. Dali was to write the text – it came only in the form of a telegram – and make the set, while I was to compose the music. I was very interested in the prospect of such a project, the more that I was always interested in painting, [and] Picasso and Dali were my favorite painters. Unfortunately, Salvador’s death interrupted our plans,” Penderecki recalled.

Probably the composer himself could not count all the awards he received. He received four Grammy awards (he received the last award in 2017 for the album Penderecki Conducts Penderecki vol.1). He also received the MIDEM Classical Award. Thirty Universities awarded him Honoris Causa doctorates. Penderecki also received many decorations, including [Poland’s highest honor], the White Eagle.

A demon for work

“I often spend several hours a day on a score, regardless of where I am, whether at home or abroad,” he said. Penderecki was not disturbed by the buzz [of the crowd] – he often composed in crowded places at airports or in cafes (in the famous cafe Jama Michalika in Krakow he would always sit at the same table) and apparently he used to write on napkins. According to the composer, “I live intensively, I am strict with myself, I force myself to write at least a few bars a day.” He usually worked at home from 6am to noon, and the radio or TV could not be turned on at that time, and during the holidays the family had to go out for a walk or to the beach.

He wrote in his own way. He often returned to pieces already written, adding successive parts as it was with the Polish Requiem – he extended the Symphony No. 8, which was first performed in 2005.

In total, he wrote over 100 pieces, including 8 symphonies and 4 operas. His most famous works apart from the Threnody and Passion of Saint Luke, are the Polish Requiem, Symphony No. 3 and Seven Gates of Jerusalem.

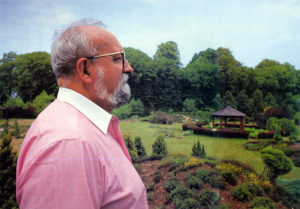

Trees – his second love

“Lonely moments spent over a music sheet are the most important hours in my life. And going for a walk in the park which is my dearest place on earth… ” – he repeated. The park [of the manor] in Lusławice was his second great passion.

Penderecki bought the manor house and park in 1974. They were in a deplorable condition, the house was completely ruined, and all the trees in the park had been cut down.

The composer kept purchasing adjacent pieces of land for years, until his garden was 30 hectares. He had dreamed of something like this since he was a child. “I am a collector and, just like a philatelist would like to have all the most interesting stamps in the world, I would like to have all beautiful trees.” Today, around 1,700 species grow in the garden. “At first, I didn’t plant ordinary trees, just collector’s curiosities. After a few years, however, it turned out that more than half of these curiosities are extremely interesting and rare, and can only be found in very good botanical gardens.”

In part of the park, Penderecki created a maze of 15,000 hornbeams, according to a 13th century plan found in France. When it grows higher, it will be extremely difficult to walk through. “I would like to introduce it to the critics who wrote about me badly, and they would have to look for a way out without the help of a guard as a punishment. [It could be] such a purgatory.”

His grandfather taught him his love for trees. To him the act of planting trees was an art. “Let’s look at the tree; it teaches us that a work of art must be rooted – in the earth and in the sky. No creative work can stand without roots.”

It seems that it is not only his trees that have already buried deep roots.

Author: Łukasz Starowieyski

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin