Olga Boznańska is one of the most important artists of the 19th and early 20th Century, famous for her original style and boundless devotion to art. She was born in Krakow, the daughter of engineer Adam Boznański, Nowina coat of arms, and Eugénie Mondan, of French origin, on 15 April 1865.

by Piotr Bejrowski

It was her mother who encouraged her to paint. Young Olga took drawing lessons, including courses organized at what was then known as the Technical and Industrial Museum. Among her teachers were Kazimierz Pochwalski, an outstanding portraitist, as well as the art collector and painter Józef Siedlecki, who gave her drawing lessons. Boznańska wanted to continue her education in Munich, which was then an important artistic centre, although in comparison with Paris or even Berlin, it was considered quite provincial. However, a group of Polish artists, some of whom she knew personally, had decided to settle down in this city. Because she was a woman, she was not admitted to the Academy of Fine Arts. Instead, she took lessons with private teachers.

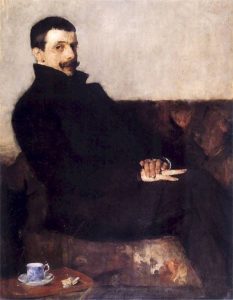

In Munich, she painted her first mature works which were received positively by both the critics and the public. Despite growing international recognition, Boznańska, an ambitious painter, was underestimated in her native Krakow. For this reason, when the well-known painter Julian Fałat offered her a professorship at the Women’s Faculty of the Krakow Academy of Fine Arts a few years later, she refused. At the same time, she gained praise for the paintings she exhibited in Vienna, Paris and London. European governments and national institutions purchased her works. Interestingly, the first of Boznańska’s paintings purchased with public money, “Portrait of the Painter Paweł Naumen” (1893), went to the National Museum in Krakow.

Boznańska developed her style very early. Already in the 1890s, she was using a dark color tone sometimes broken by contrasting bright elements. However, she did not succumb to the latest fashions in art. She did not use bright colours, nor did she take up the open-air painting so characteristic for the impressionist artists who were so popular at that time. Unlike the Impressionists, she tried to bring out the psychological depth of the depicted personage. She attached great importance to details that emphasized features and character. Boznańska did not use varnish, thanks to which the texture of her paintings seemed more matte, giving the final work something of an unfinished look. Most often, she utilized a neutral background, which also directed the viewer’s attention to the presented figure. She was surprised when her work was labelled Impressionism. “Me and Impressionism?”, she asked in response to the claim.

Probably one of her most famous paintings was created during her stay in Munich. She was not yet thirty when she painted “The Girl with Chrysanthemums” (1894). In this picture, we can first of all notice her rejection of the Munich tradition and her inspiration by the mood characteristic of the work of James Whistler.

Her portraits brought her great fame. Thanks to the methods she developed, which consisted of gently applying paint and waiting for it to dry, the whole work does not look dirty and disordered, which is easy when using dark tones, in which brown and grey predominated. The stretcher used by the artist intensified the intended effect. Mostly she painted on gray cardboard which absorbs oil paint. A model posing for a portrait by Olga Boznańska, however, had to be patient. The artist painted very slowly, and it took several dozen sessions to complete a work.

In 1898 she moved to Paris, where she would spend the rest of her life. However, she was unable to make a living from her work and relied upon her father’s financial assistance. At the same time, she managed her savings poorly. As soon as she enjoyed an inflow of cash, she quickly distributed it amongst those in need. Moreover, they, after knowing her address, often reached out to her for help. After her father’s death in 1906, her primary source of income was the rent from the Krakow house she inherited from him. At the same time, Boznańska could count on the support of friends.

Boznańska never married. As she emphasized herself, her painting studio gave her the greatest happiness and safety. This dark, gloomy and stuffy space allowed her to devote herself entirely to her beloved art. Boznańska rarely used the entertainment offered by the French capital, but she did not shun company. There were often many guests in the studio.

After the First World War, Paris changed. New fashions appeared, new trends in art emerged, and the tastes of the viewers changed. Then Boznańska received fewer commissions. However, she remained faithful to her style. At the end of her life, tragic events left their impact – both her sister’s suicide and the outbreak of the Second World War, which cut her off from relatives living in Poland. Boznańska died in solitude on 26 October 1940 at the Hospital of the Sisters of Mercy in Paris.

Author: Piotr Bejrowski

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin