In the old times in Poland, the period from New Year’s Eve until the end of the Carnival season was filled with carefree and imaginative fun based on folk beliefs, customs, and rituals. People played, sang, danced, and ate with abandon in the manors, houses, and taverns. A sense of rejoicing was everywhere. In addition, on the last day of the year, people searched for signs and organized fortune-telling sessions to help them predict the future.

by Anna Wójciuk

Old Polish New Year’s Eve

In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, it was believed that the last day of the year would determine the success of the upcoming year. Therefore, in many Old Polish houses, folk customs were observed to ensure peace and happiness for the coming year. These customs included fortune telling, offerings to benevolent spirits, and preparations for a New Year’s Eve party, which, according to folk beliefs, was a symbol of rebirth and awakening to life after the dormancy of the long, harsh winter.

A popular New Year’s Eve custom was to prepare ritual bread in various shapes and offer it to household members, guests, servants, and neighbors. Pieces would also be given to the animals. It was, of course, magical. It was a common belief in Old Polish society that ritual bread prepared on the last day of the year would bring health, happiness, and prosperity to the farm in the new year.

New Year’s prophecies were also sought through various forms of divination. Fortune-telling sessions were organized and were most willingly attended by unmarried maidens who were eager for any sign of a future husband, as spinsters were looked down upon in Old Poland.

The fortune-telling was supposed to help maidens discern the identity of their intended. One folk custom involved bringing in the firewood as it was believed that the woman who brought in an even number of sticks would soon be married. Divination by examining melted wax or lead or throwing shoes were also popular. For example, a young lady would stand or sit with her back to the door, and throw a shoe over her shoulder. She could count on a quick marriage if the shoe landed with the tip against the door. Another common superstition encouraged maidens to stare into a mirror as the silhouette of their future husband was supposed to appear in it.

Old Polish New Year

In Old Polish times, the following proverb served as guidance: “As is the New Year’s Day, so is the whole year,” therefore, troubles were avoided on the first day of the new year. The day began early in the morning as people prepared a ceremonial bath. They would first throw silver coins into a bowl and then cold water, finally, they would thoroughly wash. Through this folk magic ritual, the bathers hoped to ensure health, wealth, and beauty.

Other beliefs were associated with New Year’s visits, especially when men were expected. In Old Poland, it was believed that a man crossing the threshold of a house brought good luck and blessings. In addition, people believed in the extraordinary power of New Year’s bread. In almost every Old Polish house, a substantial loaf of fresh bread was placed on the table on the first day of the new year. This custom was supposed to protect them from poverty and hunger by ensuring that the household had plenty of food throughout the year.

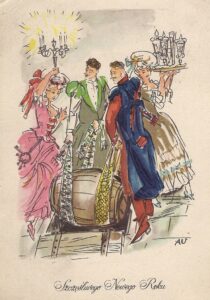

In the first days of the new year in towns and villages, you could meet people singing carols dressed in New Year’s costumes. They would visit manor houses, where they brought good wishes to their hosts, sang carols, staged humorous performances, and played various pranks on the household members. Because of the noise and loud laughter, it was immediately apparent in which mansion or house the carol singers and New Year’s mummers were. Following the accepted custom, the visits of carol singers and mummers were a chance for their hosts to demonstrate their goodwill. In Old Polish times, it was believed that a friendly welcome, with gifts and donations, was a confirmation of the homeowner’s munificence regarding their house, family, and farm.

It is worth noting that the Old Polish custom of New Year’s wishes and gifts was very prevalent. According to tradition, to receive a New Year’s gift, one had to address a wish to the person who was offering the gift. The Old Polish community attached great importance to New Year’s wishes. They believed that wishes which came from a sincere heart would soon come true. However, wishes were offered to others according to a particular etiquette: rich social classes wished the poorest people all the best, lords and hosts expressed cordiality to their servants, bachelors came with congratulations to maidens, and children offered their best wishes to their parents. The most common wishes were: longevity, health, abundance, flourishing crops, early marriage, happiness in marriage, and the joy of offspring.

Gifts were also given according to custom. Thus, the ruler gave gifts to courtiers, great lords and hosts gave gifts to servants, and parents gave gifts to their children. Traditional Old Polish gifts included farm animals and pets, costumes, shirts, trousers, clothing accessories, footwear, cold weapons and firearms, cups and goblets, liquors, homemade food, sweets, etc. It is worth remembering that in Old Poland, gifts were usually not given during Christmas but were customarily given on New Year’s Day.

Old Polish Carnival

The name Carnival comes from the Western European tradition and means: farewell to meat and, more precisely, the end of social meetings, games, and entertainment. Carnival season preceded the period of Lent, so during Carnival, it was essential to have a good time. That is why Old Polish Carnival was colorful, boisterous, and loud. It was a time of playfulness, crowded social meetings, lavish feasts, colorful balls, crazy dances, parade masquerades, winter sleigh rides, matchmaking, engagements, and weddings.

During Carnival, there were plenty of social gatherings and balls where people discussed, joked, played cards, hunted for pleasure, tasted liquors, overate, and danced. Dancing was an inseparable element of carnival fun. They danced almost everywhere, at the royal court, in magnate palaces, manors, houses, cottages, taverns, and on the streets and markets. The musicians played, the singers sang, and the rest danced, clapping to the rhythm of the dance. Dignified, majestic, and slow dances dominated the royal, magnate, and noble courts. It was utterly different in peasant houses and taverns, where everyone enjoyed energetic and lively dances with an insanely fast rhythm. In every social stratum, creating a dancing chain that would move to the rhythm of music and singing was common. Sometimes the carnival dances were interrupted by performances from traveling jugglers and buffoons.

Dancing wasn’t just about fun. It also played a vital role in courtship. When the bachelors were ready to marry, they invited the girls they liked to dance. It was an excellent opportunity to get to know their chosen one better. The families of the young women carefully watched all the applicants, and the one they liked most was encouraged to ask for the maiden’s hand. Carnival in Old Polish society was considered a prime time for matchmaking between young couples and a great opportunity to marry off a daughter. However, the courtship was only sometimes successful. A reputable bachelor had to come from a respectable family, possess appropriate wealth, and demonstrate impeccable manners.

It is worth noting that many other entertainments were organized during the carnival season, among which masquerades were particularly popular. All social classes took part in this game, thanks to which people from the lower classes could join the company of influential gentlemen and elegant ladies. In short, everyone had fun with everyone. Nevertheless, to participate in the masquerade, the whole face needed to be covered with a mask and the identity of the participant needed to remain unknown. The most fashionable masks were made by Krakow artisans, although for financial reasons, not everyone could afford such a mask. However, this did not discourage participation in the masquerades. Masks were made by hand at home, and their appearance depended on the maker’s talent. For fun and even greater secrecy, various disguises were often put on, with gender-swapping being particularly popular. They also dressed up in the robes of the clergy, kings, and princes.

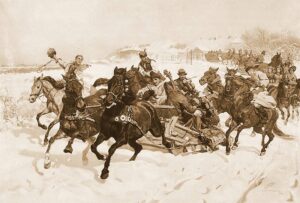

Sleigh rides were also common, i.e., colorful winter excursions with music and singing and, sometimes, dressing up. Horses with colored manes pulled the sleigh, and musicians played melodies on their instruments while the sleigh ride participants donned colorful costumes and sang funny songs. The higher-class favored the sleigh rides, such as the rulers, magnates, and nobility. Nevertheless, rich and poor alike enjoyed themselves in their open sleighs on these occasions, and these events were popular. To avoid unnecessary confusion, participants would choose a sleigh ride mayor to mark a route which would pass by the houses. The signal that started the event was a curved stick passed down among the participants.

Apart from having fun, one part of the sleigh ride included visiting relatives, neighbors, and friends. Guests, approaching the house of someone they intended to visit, shouted: “Hey, sleigh ride, sleigh ride!” or “Open sleigh goes, eats, drinks and goes!” This exclamation was a signal to the host that the revelers were near. Sleigh ride participants were always warmly welcomed and kindly received. After many courtesies, conversations and refreshments, the hosts were encouraged to join this carnival entertainment. It was believed that the greater the number of participants, the merrier and more fun the sleigh ride would be.

Shrovetide – the last days of Carnival

The last three days of the Carnival season before Lent were known as Shrovetide and also called the “Days of Bacchus.” Then the fun was almost non-stop. Lent was approaching, which meant spiritual silence and fasting. It was time to bid farewell to high-calorie food. According to tradition, in the last days of Carnival, Old Polish tables were filled with only fatty and sweet dishes, such as bacon, sweet pancakes, and yeast cakes resembling donuts. In wealthier homes, the last Carnival dinner with bread was prepared and included dairy products and various fish dishes, which were eaten at midnight. It was time to bid farewell to the season of celebration with songs praising carnival pleasures and the abundance of the table.

Balls and parties were organized to end Carnival with a bang. The most spectacular, lavish, and famous banquets were held at the royal court and in magnate and grand estates. The entertainments of the richest were distinguished by their exquisite dishes, the large number of orchestras, and the variety of entertainment. The poorer social classes organized dance parties in taverns.

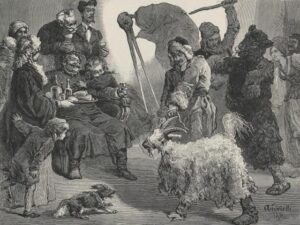

In the last days of Carnival, a colorful parade of mummers would take place in towns and villages, entertaining the Old Polish community with humor, tricks, singing, and dancing. Visiting nearby farms, they recited humorous poems and cajoled the hosts to provide refreshments and gifts. The Old Polish community, famous for its hospitality and generosity, welcomed guests kindly, and these mummers were also welcome. It was commonly believed that happiness and prosperity always accompanied them.

The celebratory exuberance of Shrovetide was due to the approach of Lent, which lasted forty days. This was a time of penance and spiritual preparations for Easter. Loud parties and social gatherings were forbidden. Every Christian’s duty was to spend this time preparing for Easter and the Resurrection of the Lord by examining their conscience calmly and thoughtfully. Carnival was a time of transition from carefree fun to silence and reflection, enabling the community to properly celebrate Easter.

Author: Dr Anna Wójciuk

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin