It is generally believed that the accords with the state authorities were signed on 31 August 1980 in Gdańsk and nowhere else. The fact that similar agreements were signed the day before in Szczecin, and after Gdańsk also in Wałbrzych, Jastrzębie-Zdrój and Dąbrowa Górnicza, is largely unknown to the public. Yet it was all of them together that were at the origin of the difficult birth of the NSZZ ‘Solidarność’ (Independent Self-governing Trade Union ‘Solidarity’).

by Sebastian Ligarski

Gdańsk

On 14 August 1980, activists of the Free Trade Unions of the Coast (Bogdan Borusewicz, Bogdan Felski, Jerzy Borowczak and Ludwik Prądzyński) proclaimed an industrial action at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk in defence of their dismissed colleagues Anna Walentynowicz and Lech Wałęsa. They were successful in arranging talks with the shipyard’s management represented by director Klemens Gniech. Over time, other enterprises joined the strike, including public transport. The list of the strikers’ demands was expanded by adding those related to guaranteeing their safety, pay rises of two thousand Polish zlotys, as well as an allowance compensating for high prices and another familial one, both equalling such benefits received by agents of the Citizens’ Militia (MO) and the Security Service (SB), and above all commemoration of the workers killed in December 1970. On 16 August, the management agreed to most of the demands and signed an accord with the strike committee. Lech Wałęsa announced the end of the strike, which many strikers did not like, particularly ones from other factories, who considered the committee leader a traitor.

Consequently, strike committee members decided to stop the workers leaving the shipyard en masse in order to continue their protest on behalf of other plants. Supported by Jerzy Borowczak, Ludwik Prądzyński, Bogdan Felski, Marek Mikołajczak, Kazimierz Szołoch, Jan Zapolnik and others, Anna Walentynowicz, Ewa Ossowska and Alina Pieńkowska managed to stop the wave of the leavers and close the shipyard gates. The crisis was averted. That moment marks the establishment of the Inter-factory Strike Committee (MKS) led by Wałęsa, and two days later 21 demands were announced addressed to the authorities (including the first and crucial one concerning the setting up of free trade unions), which were called for talks. Notably, the MKS did not include such plants as the Northern Shipyard, the Gdańsk Ship Repair Yard, the Gdańsk Port Management Authority or the Gdańsk Refinery. Attempts at talking them into joining the strikers were met with open hostility. It was only Deputy Prime Minister Tadeusz Pyka’s unrealistic promises that made them change their mind and want to join the MKS. For talks with the governmental commission led by Deputy PM Mieczysław Jagielski (experienced in the July 1980 negotiations held in Lublin area), Wałęsa sat on an expert commission headed by Tadeusz Mazowiecki. That was a group of intellectuals, economists and sociologists supporting the MKS. It should be noted that the shipyard was wide open to journalists, particularly ones from the West, who were providing live coverage of the events in Gdańsk. In the shadow of the talks, preparations were going on for quelling the strike by authorities as well as a broad propaganda action aimed at weakening the power of the protest and presenting it in the worst possible light. The authorities were trying to stop the strike from spilling across the country, although SB reports left no illusions as to it’s being just a matter of time.

The negotiations between the MKS and the governmental commission lasted until 31 August 1980. Jagielski not only consented to implementing the first point on the list of demands but also to guaranteeing the release of political prisoners, as demanded by the strikers in the final hours of the protest. On 31 August 1980, Lech Wałęsa and Mieczysław Jagielski signed an agreement in the BHP (Health and Safety) Hall of the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk, an arrangement meant to guarantee to the workers the creation of an independent union and an improvement of the country’s social and economic situation.

Szczecin

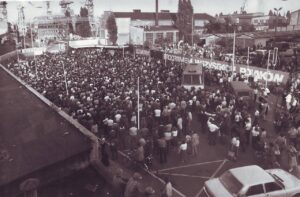

On 18 August 1980, that is four days after the outbreak of the protest in Gdańsk, the capital of Western Pomerania saw the start of a strike first at the Parnica Ship Repair Yard and then the region’s largest plant, the Ludwik Warski Shipyard. The centre of workers’ industrial action a decade previously, took up the challenge of fighting for workers’ rights once again. Unlike in December 1970, however, the shipyard’s staff did not take to the streets and did not go to the building of the Voivodeship Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR). They stayed put, announcing an occupation strike and making specific demands of those in power, the key one being free trade unions independent of the party and the government. A total of 36 demands were made. A governmental delegation came to Szczecin headed by Deputy Prime Minister Kazimierz Barcikowski. The MKS was led by Marian Jurczyk, a shipyard warehouse man. No external (particularly foreign) experts or journalists were invited. The workers were seeking to avoid being suspected of carrying out a strictly political action, and they did not want to identify with specific sections of the democratic opposition. Although contact with Gdańsk was established, the negotiations with the governmental commission were independent of it. The Editorial Committee, made up of members of the governmental commission and the MKS, negotiated the text of the accord paragraph by paragraph. Jarosław Mroczek, the committee’s chairman from the MKS has said: ‘When a common position had been agreed, we would go to the plenary hall to present the accord and the assembly gave it the green light or not. In the absence of an agreement, we would continue discussions looking for a compromise. Those were difficult talks. Each of us strikers had never taken part in such negotiations before. We were very, very gullible.’

The accord was struck in the night of 29 to 30 August. Around 1 a.m., Kazimierz Barcikowski and his advisers (Prof. Adam Łopatka, Prof. Zbigniew Salwa and Dr Stanisław Baniak) came to the shipyard. For the following several hours, the accord was being polished, particularly as regards its first point (concerning free independent unions). The discussions were still going on whether it was to concern Szczecin only or the entire country. One of key roles at the final stage of the strike and when working out the eventual reading of the first point was played by Janina Waluk and Andrzej Tymowski, the advisers of the Szczecin MKS who had arrived at the shipyard several hours previously. They pointed out the direction and laid foundations for the final wording of the first demand so that it could be acceptable to Mr. Barcikowski. They clearly broke the impasse and horn-locking in which both parties were stuck.

The final wording of the first point was far-removed from the formulation included in the original demands. The agreement provided for the establishment of self-governing trade unions, ‘which shall be socialist in nature in compliance with the Constitution of the Polish People’s Republic, and the following principles shall be assumed: upon the end of the strike, the Strike Committees will become Workers’ Commissions and hold, as needed, universal, direct and secret elections to Trade Unions Authorities. Work shall be carried out on drafting an Act of law, Statutes and other documents specified in Article 3 of Convention No 87, to which end a relevant work schedule shall be prepared.’ That provision marked Barcikowski’s success as it gave the authorities the possibility to nip independent workers’ initiatives in the bud, quickly and relatively easily. Yet a greater sense of victory was felt by the striking workers for whom the case was clear: they successfully fought for free trade unions.

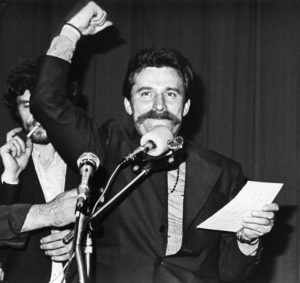

The signing of the accord began at 8:00 hours, in the already historic shipyard canteen. It had been the centrepiece of the December 1970 events, and particularly those in January 1971. It was there that Edward Gierek met with shipyard workers – for the first time in the history of a communist state – as the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the PZPR, for an open debate in the night of 24 to 25 January 1975. ‘At eight o’clock, the canteen is in perfect order. The tables are aligned, the tablecloths stretched tight, and the floor carefully swept. Whoever could afford it has been refreshed. The faces are lit up, attentive in each expression – confidence and mobilisation. The human assembly in top shape. No signs of fatigue. An extraordinary silence. Very many journalists […] 41 accreditations. Some foreign cameras next to a few Polish ones. Microphones on poles. A flower garden against the backdrop of a curtain more impressive than ever,’ wrote Tomasz Zalewski and Małgorzata Szejnert. In the name of the strikers, the agreement was signed by Marian Jurczyk, Kazimierz Fischbein and Marian Juszczuk, and by Kazimierz Barcikowski, Andrzej Żabiński and Janusz Brych for the governmental side.

Wałbrzych

Until 27 August 1980, July and August strikes in Wałbrzyskie Voivodeship had been effectively pacified by the authorities promising pay rises as well as better welfare and living conditions. The events of the second half of 1980 in the country and the announcement of strikes in Wrocław-based enterprises on 26 August 1980 led to an immediate response in Wałbrzych. Just like in Szczecin and Gdańsk the expectation was that the protest would be triggered by work stoppage in both shipyards, in Wałbrzych or in the region of Upper Silesia industrial action was impatiently awaited in mines. In Wałbrzych, most predestined – given its employment level and importance – was the Thorez mine (named after the Italian communist Maurice Thorez).

It all began in the Chwalibóg shaft of the Thorez mine at 13:30 hours. ‘Four of them went around: Kazik Żołnierek, Rysiek Kmit, Leszek Świder and Zbigniew Włodarczyk. They started talking to the people. The responses varied. Some were afraid, some reluctant, most incredulous that could bring some specific solutions. […] Before the work commenced, heads and foremen would always brief the miners about their tasks. That was the case on that occasion, too, yet no-one moved from their place once the tasks had been distributed. They were looking at one another, there were audible whispers. A tense atmosphere could be sensed. Everybody waited for someone to call for an industrial action. That was entirely spontaneous. We had not arranged that beforehand,’ Ryszard Kmit recalls.

The miners from the Julia shaft learnt that the Chwalibog shaft had begun a strike and they also stopped working. They both joined forces and communicated their 19 demands to the management, among which were: free Saturdays and Sundays, regulating the manner of vocational illness recognition, lowering the retirement age and the number of underground work required for securing social benefits, freedom of speech, removal of privileges for narrow professional groups, separating sports clubs from enterprises as well as the settlement of activities by occupational physicians. The strike committee was headed by Kazimierz Binecki.

‘In all truth, we did not know the meaning of the word “strike”,’ recalled Idzi Gagatek. ‘We did not know what it meant to go on strike. It was only thanks to the French miners working in “Julia” that we knew what to do. They told us to close the gates, place guards everywhere, cut off all telephone lines but one and take control of the entire plant.’ The strike’s motto was ‘We want bread and we support Gdańsk’.

On 28 August, entire Wałbrzych was already on strike, including mines and public transport. An Inter-factory Strike Committee was set up at the Thorez Hard Coal Mine headed by Jerzy Szulc of the Wałbrzych Hard Coal Mine. On 30 August, a four-person MKS delegation went to Wrocław in order to establish contact with the local MKS. It was received by Jerzy Piórkowski, chair of the Wrocław MKS, and Władysław Frasyniuk.

Since Wałbrzych supported Gdańsk and it was not clear what to do next, Jan Sęk was sent to Tri-City to explore further steps to take. Sęk arrived at Gdańsk already after the signing of the accord: ‘I remember Lech,’ Sęk says, ‘coming to the window. The crowd applauded. He was saying that everyone had to find a way to overcome their own problems.’

When Sęk returned to Wałbrzych, it turned out that the strike had ended there, too. As they were to express solidarity with Gdańsk, the local strike was considered terminated. A conflict flared up within the MKS as representatives of the mining industry were of the opinion that their demands had not been acknowledged. To them, more important were the negotiations going on in Jastrzębie-Zdrój with the commission headed by Minister Aleksander Kopeć. Tension increased by the hour as some protesters resumed work, while miners from the Victoria, Wałbrzych, Thorez and Nowa Ruda mines as well as staff of the Lower Silesia Mining Equipment Enterprise PW, Haulage and Transport Company Transgór and the Material Economy Enterprise decided to continue negotiations with the governmental representative Gerard Kroczek, Vice-Minister for Mining. He came to Wałbrzych around 30 August 1980. He held talks with the MKS represented by Jerzy Szulc, supported, inter alia, by Prof. Bolesław Gleichgewicht and the lawyer Zbigniew Karski. As the participants of those events recall, ‘the talks were very difficult and the governmental side often used the breaks to consult its decisions with Warsaw and Katowice’.

Finally, an agreement was signed on 2 September 1980, featuring 27 points, mostly related to the miners’ welfare and living-standard issues. Striking were a few paragraphs on miners’ health (mainly pneumoconiosis and obligations of occupational physicians regarding that professional group). The miners demanded free Sundays and a guarantee of 16 free Saturdays provided for in legislation, setting the retirement age at 50 or 25 years of underground work, abandoning the four-brigade system as well as a gradual implementation of the five-day working week. A couple of points were directly related to the plants represented in the MKS. The governmental side made the implementation of some points dependent on the outcome of the talks held in Jastrzębie-Zdrój or other circumstances, which opened a way for postponing or abandoning them.

Jastrzębie-Zdrój

The strikes in Jastrzębie-Zdrój began in the night of 28 to 29 August. They embraced the two largest mines, Manifest Lipcowy and Borynia, strike committees established at both. Initially, the authorities tried to nip those initiatives in the bud by sending in a governmental commission headed by the Minister for Mining Władysław Lejczak. It turned out, however, that the Minister’s manipulations and lack of due authority led to protest escalation. Both mines called into being an MKS, led by Jarosław Sienkiewicz of the Borynia mine. Despite strike termination in Szczecin and Gdańsk, the strike continued and on 1 September the authorities sent to Jastrzębie-Zdrój a new commission led by the Minister for Heavy Industry Aleksander Kopeć. The accord was signed in the wee hours of 3 September, and it not only guaranteed the creation of new free trade unions but also, inter alia, removal of the four-brigade system in the coal industry, recognition of pneumoconiosis as an occupational disease or, last but not least, the arrangement that all Saturdays would be free as of 1 January 1981.

‘Although some of the demands accepted pertained to miner welfare, they later mattered for employees across the country, for instance pneumoconiosis frequently found in miners was recognised as an occupational disease and the inclusion of other illnesses into that category was at the same time made dependent on the opinion of trade unions, something that later benefitted other industries, too. Family benefits were to be uniform in entire Poland, which meant their increase to equal levels binding for the army and militia.’

Dąbrowa Górnicza

Protests in Katowice Voivodeship began on 28 August 1980 at the Rolling Department of the Katowice Large Steelworks (located in Dąbrowa Górnicza). Talks with the management related to, inter alia, information in the media as to supporting Gdańsk, as Zbigniew Kupisiewicz said: ‘so that they know on the Coast that we support their demands and we recognise them as ours and we think that the negotiation prolongment is a fault of the governmental side rather than the strikers.’ The steelmakers were promised that the message would be published yet as it never was, the protest began to intensify. Their demands were written down, and a strike committee (later the MKS) appointed, headed by Marek Fabry. In the night of 31 August to 1 September, the strike was suspended due to the accords signed in Szczecin and Gdańsk. On 4 September, the strike was formally terminated, with the MKS transformed into the Workers’ Commission headed by Andrzej Rozpłochowski, yet no agreement was concluded waiting for a governmental delegation ‘to discuss guarantees of the implementation of the arrangements negotiated by the MKS in Gdańsk and included in its accord with the governmental commission.’ Headed by the Minister for Steelmaking Franciszek Kaim, the commission came to the steelworks on 9 September 1980. After two-day talks, an accord was signed. Its importance ‘consisted mainly in the fact that it concerned the guarantees of the implementation of the Gdańsk accord as regards the creation of structures of independent unions. State administration bodies, the MO and the SB, as well as the management authorities of industrial plants and their political organisations were committing to not just accept the creation, organisation and functioning of independent unions but also not to counteract it. Detailed guarantees concerned such matters as: exemption from the work duty of persons with trade union functions, retaining remuneration for the time of performing such functions, making available, by industrial plants and state administration bodies, premises for use by trade union cells, access to the media, the possibility to co-decide on employee and social maters, the possibility to open bank accounts by trade union structures ‘in order to deposit their membership fee income’, as well as participation of the unions in works on the Act of law on trade unions, workers’ self-government and the amended Labour Code. Additionally, guaranteed was the safety of strike participants, members of Inter-factory Workers’ Commissions and workers committees, their families and persons supporting such structures.’

In summary, it is worth remembering that those five accords concluded between the state authorities and striking workers provided for merely a framework for the creation of a new trade union independent from the authorities. As for the rest, the members of the Inter-factory Founding Committees / Inter-factory Workers’ Commissions had to create it themselves. The authorities had no intention to assist them but sought to break and antagonise them. Throughout Poland, accords were signed between strike committees and directions of individual plants or their associations. The five accords broke the barrier of fear and incapacity, and offered a renewed hope for change.

The breakthrough came on 17 September 1980, a symbolic date for the Poles, where after dramatic talks the decision was made in Gdańsk concerning the creation of a single union, the Independent Self-governing Trade Union ‘Solidarity’, which soon went beyond the union context becoming a social movement.

Author: Sebastian Ligarski

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin