Sometimes literature sets up things for a revolution, although it usually takes some time until it actually breaks out. A generation needs time to read Rousseau’s Meditations, The Sorrows of Young Werther, Marx’s Capital, or The Catcher in the Rye. One can count on the fingers of one hand the literary works that directly triggered a political uprising. The most popular example is La muette de Portici – a slightly forgotten opera by Daniel Auber, whose libretto (written by Germain Delavigne) put Brussels’ burghers into a state of elation which initiated a revolution and in 1830 brought about Belgium’s independence 15 years after the Congress of Vienna.

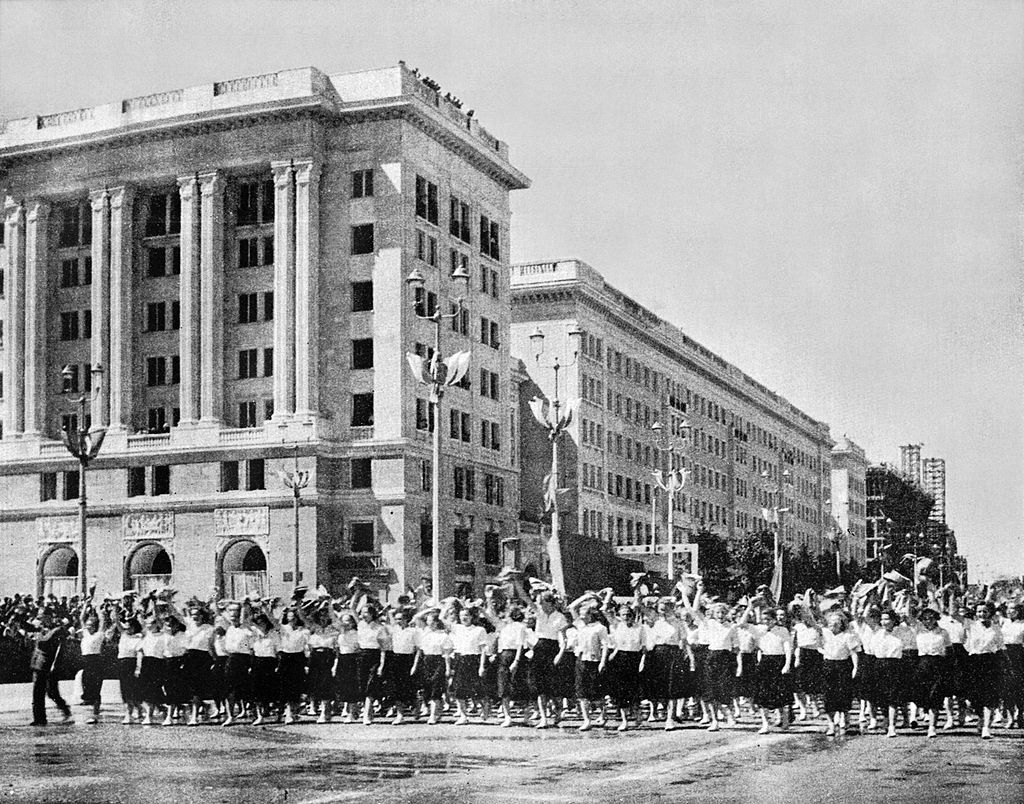

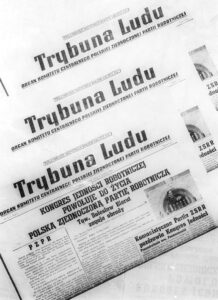

When it comes to more recent events, only Adam Ważyk’s “Poem for Adults” probably caused a similar outbreak. It was published on August 21, 1955 in the “Nowa Kultura” weekly and was condemned by the leadership of the Communist party. Nevertheless, it was sought after by readers. On the “black market”, a copy of “Nowa Kultura” with the poem, originally sold for a nominal price of 1 zloty 20 groszy, sold for 250 zlotys, and sometimes for 300 instead. Pages were even torn out of copies in library collections. It was massively copied in “Chinese duplicator” mode through dictation to friends. And although at the end of the summer of 1955 no barricades were set up on the streets of Warsaw to defend Paweł Hoffman, who had been dismissed by the Communist party from the post of editor-in-chief of “Nowa Kultura”, a year later, in October 1956, when Poland quit Stalinism and celebrated the election of Władysław Gomułka as the new secretary of the Communist party,, the vast majority of the crowd of one hundred thousand singing ‘Happy Birthday’ knew the poem by heart – from the weekly, from copies or at least from rumours.

The poem itself? Adam Ważyk, a then 50-year-old poet, who was first fascinated with futurism and surrealism, and later also wrote short stories, novels, rhymed marching songs (during the war), as well as essays and literary criticism with which he promoted the doctrine of socialist realism in the early 1950s. Still, he was an expert in irony. In fact, when it comes to the poem, it consists of fifteen short fragments, mostly written in blank verse – detached scenes, sometimes constituting a lyrical picture, sometimes – an original, tart commentary on the reality of the People’s Republic of Poland in 1955. It contrasted sharply with the reality: the country was at the peak of its industrialization and modernization momentum – a Five-Year Plan – copied from the Soviet reality, a detailed, though greatly overestimated in its particulars, project of the expansion of steel plants, power plants and children’s clinics throughout the country. Meanwhile, the narrator of the “Poem for Adults” reflected on the monumental districts erected in the centre of Warsaw:

Squares turn like cobras,

houses stand like peacocks,

give me any old stone,

and I’ll be back in my city.

Or he would refer to idealism the pathos of the visionaries with irony:

They came and cried:

“Under socialism

a hurt finger does not hurt.”

They hurt their fingers.

They felt the pain.

They began to doubt.

Whereas in the best-known passage, he described the brutality and primitivism of the “new working class”, a generation recruited for great construction of socialism, in the first place – the metallurgical conglomerate in Nowa Huta:

The great migration building industry,

unknown to Poland, but known to history, (…)

in coal gas and in slow, continuous suffering,

the working class is shaped out of it.

There is a lot of refuse. So far, there are Frits.

The Frits – as the poem implied – consisted of drunkenness, debauchery, robbery that were common and in part the inevitable result of the tragic living conditions.

It may be shocking that similar phrases, which seem banal, and, at best, crumbs of “black realism”, shocked the public opinion and the authorities. However, it was indeed a shock – against the background of the cultural policy imposed since 1949, and even more so when we take into consideration Adam Ważyk’s participation in it.

One of the aspects of Poland’s full subordination to the Soviet Union in 1949-1955 was the imposition by Moscow of patterns and artistic prohibitions. The doctrine of socialist realism, outlined in broad terms by Stalin’s henchman Andrei Zhdanov, condemned any avant-garde elements or experiments with form and innovation which could be described as “formalism”. It was to be replaced by a rough and literally understood realism – devoid of any element of verism or naturalism. Literature and art were to be fully “in the service of propaganda”, as it was called, to shape positive models and “praise the working people.’’ Add to this the requirement of “folklore” and “egalitarianism”, which is also part of the doctrine advocating simplicity of content, exclusion of all kinds of “games with the reader” or irony, it is not difficult to imagine the result.

It was easy to incorporate it into literature and art (disputes over “socialist realism” in music continued throughout the Stalinist six-year-old plan, resulting in a considerable number of mazurkas and mass songs). Novel pages, canvases and monuments featured steelworkers and milkers in a slightly heroic manner, with a small admixture of engineers, security service officers and landscapes, all more beautiful than in reality. All other topics (or at least attempts to include “production” themes other than naturalistic ones in the spirit of Zola and Courbet) were rejected by censors and editors. Pre-war as well as young rebellious artists had to adapt to the style or write and paint “for the drawer” (many chose the latter). The introduction of the doctrine took place within a few months: one of the most important stages was the congress of the Polish Writers’ Union in January 1949, with Adam Ważyk as one of its leaders. He was already a known author at that time: a pre-war avant-garde writer, after the outbreak of the Second World War and the invasion of Eastern Poland by the USSR, he was among the intelligentsia and activists supporting the “pro-Moscow” orientation, and after 1945 he was considered one of the grey eminences of Polish literature. “He became a herald of socialist realism. He tormented us all terribly „, recalled the writer and journalist Stefan Kisielewski years later.

He did torment others, yes – after refining the doctrine of socialist realism, and then standing guard of it, with the help of pathetic introductory and critical articles. In the meantime, however, after Stalin’s death in March 1953, the process of lifting some of the rigours began, also in literature and culture, called the “thaw” after the title of the novel by Ilya Erenburg. It proceeded very slowly, in proportion, one might say, to the arctic frost of Stalinism. The apogee of changes took place in 1956 – the year of the 20th Congress of the CPSU, during which the crimes of Stalin were publicly announced for the first time. The same year changes came to the satellite countries, culminating in a political turning point in Poland, and in Hungary – the tragedy of a suppressed uprising. A year earlier, when Ważyk’s “Poem for Adults” was published, it was still impossible to talk about the end of socialist realism. However, the first copies of previously forbidden American or French authors appeared, the grotesque story “The Great Lament of a Paper Head” by Jerzy Andrzejewski circulated in the copies, and the realistic, bitter short story “A Village Wedding” by the renown writer, Maria Dąbrowska, was published in the press. In the summer of 1955, the so-called The exhibition of Young Art took place, which for the first time showed works in a manner other than solemn realism – and then, in the middle of the summer holiday, “Poem for Adults” appeared in “Nowa Kultura”.

The propaganda counteroffensive was undertaken almost immediately: the author was ridiculed, accused of “a spiritual crisis worthy of an eighteen-year-old” (Jerzy Putrament), “unmasking hysteria” (Bohdan Czeszko) or “anti-party speech” (Stefan Żółkiewski). Within a few days, the party authorities dismissed the editor-in-chief of the weekly, an experienced communist, Paweł Hoffman. In his memoirs published a quarter of a century later, Ważyk remembered that he was seriously afraid of being arrested.

It is significant that the criticism of “Poem for Adults” was, as it were, going in two directions. Apparatchiks and critics who were high in the party’s hierarchy treated Ważyk’s work in a very principled way, accusing it of its deviation from Marxism, its “hypercriticism” and “defeatism”, i.e. weakening one’s own image, unacceptable in the logic of the struggle between two systems. At the same time, he was reproached between the lines, for his earlier involvement. “In such a tone can speak only a person who is clean of faults”, literary critic Ludwik Flaszen reminded Ważyk. Wanda Wasilewska herself worried about the matter – in the 1940s one of the architects of the new political order in Poland, Stalin’s associate, living in the USSR from the beginning of the 1950s. “I am sending you a poem by a well-known Polish poet awarded with state orders and prizes, a party member, announced on 21 August 1955 on the front page of the official weekly issued by the Polish Writers’ Union – in the original and in a literal translation,” she alerted Nikita Khrushchev, then the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU. In September, the party authorities met at a conference with the participation of party writers, which was to condemn Ważyk. It’s just that some authors stood up for him.

At the same time, younger critics and journalists acted in a peculiar way, pretending to take Ważyk’s bitter irony at face value, they seemed to take seriously his definition of the new working class as “Frits” – and argued with him (or rebuked him) in the name of human dignity, which Ważyk allegedly betrayed. It was an interesting rhetorical move, a kind of accusation of “classism” avant la lettre. In September, a radio report was released under the eloquent title “Frits Speaking”, presenting a discussion on Ważyk’s poems organized at the plant in Nowa Huta. In the same month, “Nowa Kultura” (now under new editorship) published a poem-replica: “Poem for the Young” by a certain Joanna Sierpińska, which was, line by line, a polemic with Ważyk’s literally treated “accusations”:

There are people in the factories

They work, they swear

They love

They argue, they dream

They think they are

just people

they don’t think

that they are

Frits.

(…)

There are miners

down there

who know that

the enemy can awaken a fire

They are not

history fertilizer

these are

just

ordinary people.

This kind of coaxing was attempted several more times. “Sztandar Młodych”, the magazine of a mass youth organization, sent its talented reporter, Ryszard Kapuściński, to Nowa Huta with the task of “verifying” Ważyk’s revelations. Kapuściński went there – and after a week he returned with the article “Such Is Also the Truth About Nowa Huta”, which showed that the situation at the “main socialism construction site” was much worse than in a few metaphorical paragraphs… Following the “Poem for Adults”, the CPSU central committee also sent to Nowa Huta, a commission that found “gross negligence” in the field of housing conditions…

This was the beginning of an avalanche. In various ways – through reportage, a documentary, andresolutions of the rank and file of the Communist party – people began to record realities, ills, and human tragedies that had no right to exist before. “I got hit right between my eyes,” recalled Jacek Kuroń, then an activist of a mass youth organization, and ten years later the leader of the “revisionists” criticizing the party.

Adam Ważyk left the Polish United Workers’ Party two years later, in 1957 – after the party withdrew its consent to establish the intellectual monthly “Europa”. In the following years, he signed the protests of independent intellectuals against censorship and repression and published successive volumes of poems in small editions. He did not see “Poem for Adults” in print after 1955 – in 1964 the poem was censored. The censorship was only abolished with the collapse of the system. But this is still better than the poet Sierpińska, who never published a verse after “Poem for the Youth”. Over the years, it was investigated whether the actual authors of the “counter-poem” were the editors of “Nowa Kultura”, terrified by the vision of the Party’s anger, or whether (such voices also appeared) an employee of the Workers’ Union Party apparatus who decided to write, under the pressure of the moment and under a pseudonym. The puzzle was never solved, and so we are left with a pun poem by Paweł Hertz that was difficult to translate, who stated that, in fact, “Poem for the Youth” was written by two sisters: Sierpińska and Młotkowska, where “sierp” stands for “sickle” and “młot” for “hammer”.

Fragments of “Poem for Adults” in translation by Stanisław Baranczak and Clare Cavanagh.

Author: Wojciech Stanisławski

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin