“This world is arranged in such a dreadful way that not even the most tender sighs can replace statistics…” observed Bolesław Prus, one of Poland’s greatest writers. The author of the novel Lalka knew what he was writing about, as his income from literature was supplemented by working in a statistics office set up by the railway tycoon Jan Bloch. So, can statistics cast new light on how we perceive the way in which Poland’s leaders are elected?

by Michał Kopczyński

Free royal elections have not proved popular with Polish historiographers. Although the idea of condemning such elections seems based on a rational analysis of events accompanying new elections, a sizeable influence on the way they are perceived comes down to the advantage a historian has over a witness to contemporaneous events, thanks to the fact that the former knows how things will turn out later. Looking back, the particular future course of events involving the fall of the First Polish Republic did not favour the affirmation of political institutions in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. And historians in the 19th century who set up the so-called Kraków School, including Józef Szujski (1835–1883), a friend and mentor to the painter Jan Matejko, or Michał Bobrzyński (1849-1935), influential author of Polish History at a Glance [Dzieje Polski w zarysie], were unsparing in their criticisms of those same institutions in the old Republic.In their opinion, it was these institutions which enflamed widespread anarchy and, like cancerous growths, eroded the very fabric of the Republic from within until it fell victim to aggressive, centralised neighbouring empires. Historians who became a part of the positivist Warsaw School were a little more understanding, having set themselves up as a reaction to the pessimism of their Kraków colleagues. Adolf Pawiński (1840–1896), Tadeusz Korzon (1839–1918) and Władysław Smoleński (1851–1926) tried to balance the accusations levelled by the Kraków School, suggesting that the last three decades of the existence of the First Polish Republic were times of recovery from serious crises. Although opponents of the Stanislaw reforms [Reformy stanisławowskie] were intransigent and influential and for a long time they were met with lack of understanding or indifference, they did lead to the Constitution of the 3rd of May. Though said Constitution was in place for little more than a year, it quickly rose to the rank of a symbol in accordance with the thought of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, expressed in his letter to political activist Hugo Kołłątaj: “If you cannot stop them devouring you, at least make sure you cannot be digested”. The polemic between the Warsaw and the Kraków Schools was not so much based on the glorification of political institutions of the old Republic, therefore, but on emphasising the rebirth which took place just as the Polish state was collapsing, divided between neighbouring great powers not because it was weak but because it had started to overcome those very weaknesses.

It does not matter which of the two perspectives, Kraków or Warsaw, we will hold up as more true, what remains most troublesome are two state traditions belonging to the old Republic, two of its most characteristic institutions: the liberum veto and free royal elections. Few contemporary historians would agree with 17th-century poet Maciej Sarbiewski: “… they alone (Poles and Lithuanians) can benefit from two of the most beautiful treasures which any state can possess: freedom and oratory, which is identical to the freedom of speech. They are the only ones to be able to elect their king”. For proponents of the Kraków School, Sarbiewski’s opinion would be blatant confirmation of the complete inability of that era’s Poles and Lithuanians to adjust to realities of the age of absolutism and centralisation. Those of the Warsaw School were more likely to listen to opinions expressed by the authors of the 3rd of May Constitution. In its Chapter VII, devoted to the topic of executive powers, it states: “The disasters which befell the king-less, they who repeatedly overthrew their governments […] and the barring of any further influence foreign powers might have over us […] indicated to our prudence that the Polish throne should be passed down through succession”. Because, until recently, no one defended free elections – which is why the opinions of reformers of the Republic have settled in this way into the beliefs of historians, much as they have done into public opinion as influenced by school and university course books. On the other hand, historians who wrote about this tradition preferred, instead of referencing Sarbiewski, to heed the critical voices of Sebastian Petrycy and Piotr Skarga, along with reports from foreigners curious about the idea of elected royalty. And as we know, starting with the Enlightenment, Poles were keen to cure or confirm their national insecurities through seeing themselves reflected in the mirrors of opinionated “others”, without ever pausing to consider whether those mirrors might themselves be crooked…

A one and only institution?

It is not my intention to defend the idea of free royal elections, yet it is worth emphasising that an electoral throne was not unheard of, some sort of curio in modern Europe. The House of Hapsburg, tsars chosen by election, while cardinals have always elected popes, as with Venetian Doges and the kings of Denmark (until 1660). In the Polish Republic, kings were elected – within a given family – since the times of Jadwiga of Poland. As far back as the Privilege of Koszyce in 1374, Louis the Great of Hungary gave tax concessions to the nobility in exchange for his daughters being given inheritance rights to the Polish throne. Before then, women were forbidden from wearing the Polish crown, and so Casimir III the Great had to honour the arrangements made with Louis. Based on the Privilege of Koszyce, the first to sit on the Polish throne was Jadwiga, joined then by her husband and equal ruler of state, Władysław Jagiełło. Subsequently, heirs to throne right up to Sigismund Augustus were chosen through negotiations with their subjects, who were compensated with all sorts of concessions by their rulers.

When in 1530 Sigismund [Zygmunt] I crowned the little Sigismund Augustus king, reputedly having been talked into it by Queen Bona, the country was in uproar. This is hardly surprising, seeing as this was a time of challenges for the newly established executionist movement, with its oligarchy which sat in the senate, supported by the king. Under such circumstances, it is hardly surprising that the coronation was seen as an assault on freedoms and an attempt to further increase the grip of the oligarchy over the state. The strength of feeling against this idea was evidenced by the fact that King Sigismund then had to issue documents twice, in 1530 and 1538, solemnly promising that a choice of successor “during the king’s lifetime” [vivente rege] would never happen again.

During the reign of Sigismund Augustus, when in due course it appeared ever more likely that he would die without children, supporters of the executionist movement put forward projects to formulate rules regulating the future interregnum. In 1554, it was suggested that a new king be chosen solely by the combined chambers of parliament, with the members’ chamber increased in size and the senate substantially cut. With political intentions behind the proposal all too transparent, the project was not moved forward for legislative consideration. As a consequence, when in summer 1572 Sigismund Augustus did indeed pass away without heirs, a series of meetings between senators became necessary in order, over the course of serious disputes, to agree on a place and procedure for selection of the new ruler.

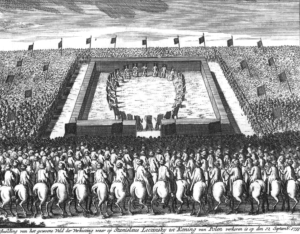

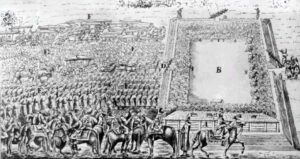

In the second half of 1572 then in 1573 at the January convocation parliament in Warsaw, the basic decisions were made which rendered the Polish version of choosing a ruler unique and unrepeatable. The name for this unique, unrepeatable rule was viritim, and it allowed every nobleman to take part in the election. This did not have a direct influence overall, as a majority vote was not needed in the Sejm – the lower house – or during the election. Yet the very possibility of a crowd of nobles taking part in an election was meant to limit ambitions of the senatorial elite (made up in any case of former executionist movement activists). The second unique quality of the Polish free royal elections was the fact that anyone, Pole or foreigner, was free to put their name forward, as long as they were a noble.

Now we come to the third aspect, which is hard to refer to as “unique” but which had immense importance for future evaluations of the election as an institution. This was the place where the nobles would converge: Warsaw. Choosing the former capital of the Duchy of Masovia appears logical from a geographical perspective – Warsaw is more or less in the centre of the country, hence Lithuanians could not complain about being left out, though they still did complain, having been forced to find different things to complain about. Kraków would have favoured the crown decidedly, but politicians of the time were not solely interested in geography and justice. Warsaw guaranteed a good turn out of Masovian nobles, and as mentioned above, the choice of location would play a great role not only at election times, but in the way these were later seen by historians.

The heart of darkness

Nobles made up at least 20 per cent of the population of the province of Masovia. In the main, they were poor nobles and so were, according to later reports, easily swayed. Cardinal Commendone, the papal nuncio who was overseeing the election of Henri de Valois in 1573, was pleased that Catholic Masovians would mount a majority against Protestants. Yet the Protestants used ridiculing propaganda against the Masovians, based on stereotypes. They did this so skilfully using printed matter that, though this was an age before the Internet and its trolls, they managed to create an image of Masovians having a Gombrowiczian “mug”, an image the latter have not ever managed to fully shake off.

Residents of Masovia were meant to be bold and keen to quarrel, yet also cowardly; talkative, stupid, superstitious, intellectually limited. Their comparative poverty was linked to a narrow range of political perspectives. When a dog sits down on one estate, or so the joke went, it must lay its tail across another. Folk songs also poked fun: I am a Masovian, a rich Masovian / each day I don a shiny new gown / […] I have a tunic, yellow and proud / in which my forefathers tended their cows / […] I have a sabre, sharpened and slick / in hours of need it’s suffered some nicks / I’ve swung it all around / chasing peasants out of town. Adding a few other classic phrases, we do end up with a ridiculous image of any resident of Masovia. With their appearances, their character was ridiculed also, as in this verse by a 17th-century Sandomierz writer, Wespazjan Kochowski: Cursed by a dark star, a snake bit a Masovian man / the snake is drunk with poison, the man as swell as a lamb.

It’s not difficult to find similar rhymes and more or less nasty sayings which use a crooked mirror to show characteristics of residents of other parts of the Polish Republic. Yet it’s the ones about people of the Masovian plains which have become popular everywhere – aided by historians set against the idea of free royal elections, who have shifted these anecdotes from historical ethnography to the main field of political history.

No wonder then that opinions by the likes of Marcin Bielski, a Protestant sympathiser, have made a real impact on historiography. In his Polish Chronicles, Bielski describes the choosing of Henri de Valois by Masovians: they have smothered the Andegaven prince with votes, though they couldn’t quite pronounce him true, and called him the Gaven Prince, and Ernest to them was not that but rather Rdest. This quote is a “ironclad” element of any historical work covering not only the first royal election but free elections in general. Were people such as the Masovians capable of making rational political decisions? The answer is obvious, much like the charge which has been confirmed: to condemn free royal elections forever. But obvious answers are not always correct, and to verify them, what we need is awful, boring statistics.

All of them means how many?

Let us now turn to those statistics. Historians writing about the election of Henri de Valois talk about 40,000 to 50,000 voters taking part, which includes some 10,000 from the Masovian region. To arrive at these figures, they rely on reports from the French ambassador Choisy and other witnesses. Yet was it possible to house – in tents, for two and a half months – and feed this number of people in the radius of a mile from the electoral field in Kamionek, just outside Warsaw? According to Swedish quartermaster accounts, a 5,800-man army needed a daily ration of 5.8 tonnes of bread, 2 tons of meat, 17,000 litres of beer and 130,000 square metres of pasture for horses. Though electors are not soldiers and their upkeep was made easier by the nearby city, situated by the fast-flowing Vistula river, it would have to have been a massive logistical undertaking. The subsequent two elections were said to have attracted a mere 10,000 to 12,000 electors. Again, however, we are reliant upon descriptive accounts without concrete evidence, which would be more believable.

It is only from the 1632 election of Władysław IV Vasa that we have more reliable figures at our disposal. These include the lists of electors – suffragia – published in print once the elections were over, and in the Volumina Legum, filed in the 18th century (though not in complete form) in the archives of parliamentary constitutions. These were also the subject of studies by historians including Włodzimierz Kaczorowski and Jan Dzięgielewski, as well as the author of this text.

In keeping with a custom established in 1632, the king was chosen on the last day of a six-week electoral parliament. Lists of electors produced during this process were then sent to the royal chambers, and on to public print. Each suffragia ended in an oral formula, pronouncing that the choice had also been made in the name of the citizens, whose vast number, right after the happy choosing of our good Sir’s nomination, unable to sign their names down owing to a hurry to get going, rode off, and other homes of the remaining brothers. The number of people who therefore appear on the lists is minimal, although we shouldn’t expect it to be in any way sizeable. Clearly, we are only talking about electors here, not passers-by or servants or the aristocratic armies stationed in Warsaw during the elections. The number of electors is shown in this chart.

During subsequent elections, the number of those voting never got anywhere near those peak figures of 40,000 to 50,000, reputed to have taken part in the choosing of Henri de Valois. The fall in the number of electors is misleading, and should be attributed to the recounting of the events of 1573 by witnesses at the gathering. The number of crown subjects at the time (not counting Lithuania) numbered some 3 million, which included 272,000 nobles. Deducting 50 per cent, representing women, who had no voting rights, and a further 30 per cent for youngsters, we are left with some 95,000 adult men of noble background. It is quite unlikely that half the Republic’s nobility would have gathered around Kamionek. We could therefore say with some sarcasm that the reports that have become part of the historical record are as believable as graphs taken from foreign-produced flyers which dreamt up stats relating to the Warsaw electoral field.

According to testimony from the suffragias, the average number of electors did not exceed 10,000. There were only three instances, in times of particular tension, that this threshold was breached. In 1669, there was a struggle concerning the pro-French camp, which had until recently supported the idea of elections being held while the king was still alive, considered by most to be a violation of freedom. Then in 1697, the election fields around Wola were swarming with crowds attracted by agitators from France and Saxony. The last attempt at electing someone without influence from neighbouring countries transpired in 1733. These were the only times such crowds descended upon Warsaw.

Let us now take a look at Masovian involvement in all this. According to the statistics quoted above, the population of Polish Crown territories towards the end of the 16th century (including the Podlasie region in the east) was made up of 60 per cent nobles. If this was the case, then for 20 per cent of them to turn out for elections should come as no surprise. Real disturbances came in 1648 and 1697. During subsequent elections, it was nobles from other parts of the Republic who mobilised their forces, which is easy to see upon comparing columns in the chart above.

All meaning how many and who took part in the elections?

The large number of nobles, the depletion of historical sources as a result of numerous wars and especially the burning of the Crown Treasury Archive during the Warsaw Uprising won’t allow us to identify those taking part in elections, as listed in the suffragies. Although the lists were published and were used by armorial authors and genealogists, few set about analysing them.

In the little that remains today of the Crown Treasury Archive, we can find main tax registers from 1662 to 1676 covering some of the Crown provinces. Those who were taking those records differentiated between wealthy nobles with their own subjects and minor nobility, because tax levels were accordingly different. We also have a surviving register from the nearest electoral field in the Masovian province, the residents of which were the largest group represented at Masovian elections. The number of taxpayers compared with those taking part in the election allows us to draw two main conclusions. First of all, Masovians were not all that active during the elections. Apart from the 1697 election and other unique events such as the mass mobilisation of the nobility during the election of Michael I [Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki], the choosing of new royalty managed to secure the involvement of a mere 10 per cent of the taxpaying public. An exception to this were lands directly bordering the electoral field: Warsaw, Czersk, Wyszogród and Zakroczym. Secondly, lands most heavily populated by minor nobility lay far from Warsaw and were, as a rule, poorly represented.

In order to learn who did visit the fields of Wola, we can use the example of the election of Michael I. In 1669, on the electoral field, 1,875 electors from the Masovian province appeared. It was possible to identify 1,294 of them, meaning 69 per cent of those present. 34 per cent of these were wealthy nobles with their own subjects, who only represented 14 per cent of the taxpaying population in Masovia. We can thus conclude that the social make up among the electors was substantially different from the social structure among the provincial nobility. Those attending elections were mostly those who took part in Sejm affairs, hence political dilemmas were not new to them. There were also groups organised by wealthy benefactors from time to time, though up to Augustus II the Strong [August II Sas] in 1697, this was an unusual phenomenon.

Ortega y Gasset at Wola

It is worth posing the question of whether the electors in the fields of Wola really were in any way worse than today’s voters. Any readers of this piece are free to start casting stones – as long as they know their way around the complexities of tax regulations, European institutions and currency politics. Are we not voting today for the candidate who looks best against a green screen, and is better at gesticulating in ways which suggest he or she is more certain about being right?

Jose Ortega y Gasset, the Spanish philosopher who died in 1955, grumbled about how the modern world was dominated by the “mass-man”. Any specialist, raised in a single discipline, when faced with politics, arts or social mores, along with other sciences, will adopt the stance of the stupidest boor – but will do it with conviction and assertiveness. Civilisation, making such a person into a specialist, has caused them to feel fully at peace with themselves and has shut them up within their own value systems, which then leads them to desire dominating fields which have nothing to do with their narrow area of expertise.

If this is how today’s voters behave, do we have the right to condemn those voting 400 years ago? If so, are we not then guilty of the sin of arrogance?

Author: Prof. Michał Kopczyński

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin