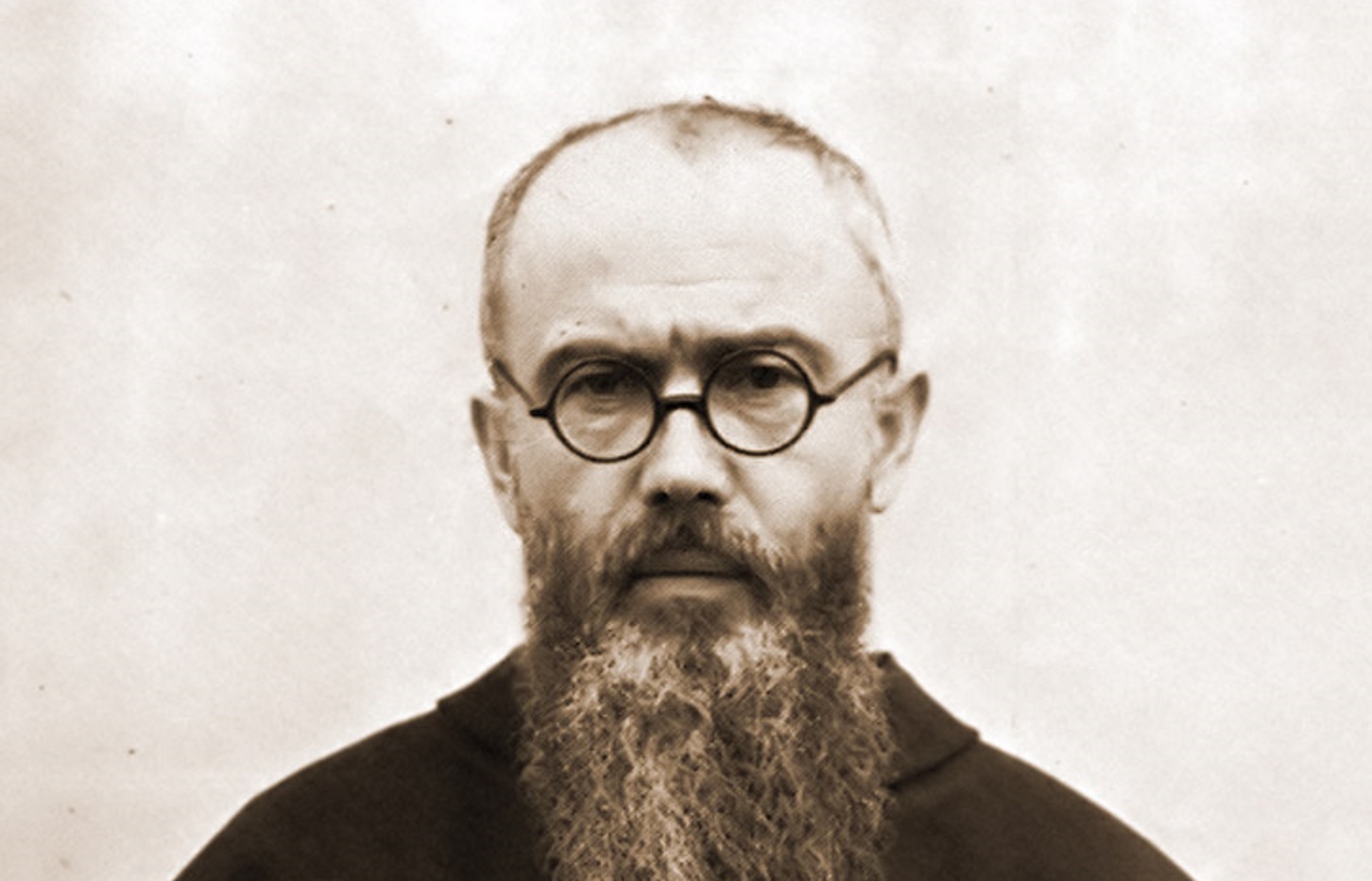

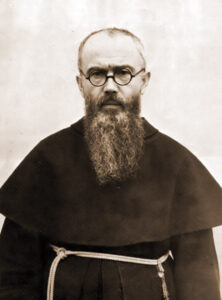

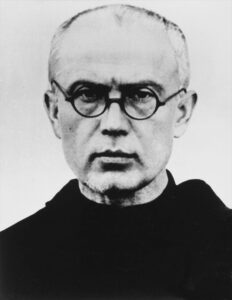

Maximilian Maria Kolbe is a symbol of faith and sacrifice for many Poles. His decision to sacrifice his life for a fellow prisoner is a heroic example of humanity during inhuman times.

by Piotr Abryszeński

As an adult, Maximilian Kolbe recalled that when he was a boy he had experienced a vision of the Virgin Mary who offered him two crowns – a white one, meaning purity and a red one – a sign of martyrdom. He accepted both.

He was born on 8 January 1894 in Zduńska Wola and was christened Rajmund. At age 16, he took the name Maksymilian along with the monk’s habit of the Friars Minor. A few years later, while taking monastic vows, he took the name of Maria.

His parents took care of his education and he showed his gratitude by being a diligent student. He received doctorates in theology and philosophy, but his interests extended far beyond these disciplines. While still a student at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome, he submitted a project named “Etheroplane” to the patent office. It was a spacecraft designed to use recoil force in order to fly. Interestingly, the modus operandi and difficulties of space travel described by Kolbe [in the documentation] are basically in line with modern scientific knowledge.

While studying in Rome in 1917, he witnessed anti-religious demonstrations, this is why together with a group of friends he decided to establish the Knighthood of the Immaculate (Militia Immaculatae) – an organization aimed at promoting the Catholic faith, especially among non-believers. In 1919, he returned to Poland filled with new ideas and founded the first circles of the Knights. There was a great interest in the activities of the organization, which was why in January 1922 the first issue of the “Rycerz Niepokalanej” magazine was published. Soon the magazine’s circulation reached a million copies, and alongside it, the Order also began to publish several other popular titles.

This, however, was not enough for Maksymilian Kolbe. In 1930, he went to Nagasaki, Japan, where he founded the “second Niepokalanów” (Niepokalanów was a town where Kolbe had founded a monastery), as well as a novitiate and seminary. A few years later, 65,000 copies of “Rycerz Niepokalanej” were printed in Japan.

When he returned to Poland in the second half of the 1930s on the orders of his superiors, the monastery in Niepokalanów had nearly 800 people and was one of the largest in the history of the Church in Poland. Maksymilian Kolbe was very curious about new tools of mass communication and wanted to use them in his evangelizing. Hence, he was interested in the first experimental shows on television. In 1938, Niepokalanów had its own radio station broadcasting all over the country. He also planned to build a film studio and an airport.

These ambitious plans were interrupted by the outbreak of the Second World War. On 19 September 1939, the Germans began the liquidation of Niepokalanów. Kolbe and his friars were arrested and sent first to the camp in Amtlitz, and then to Ostrzeszów. On 8 December (on the celebration of the Immaculate Conception) he was unexpectedly released from prison. He immediately returned to Niepokalanów, where he began to prepare places for people displaced from the Warta Region created by the Germans, organizing craft workshops and a sanitary department for them.

On 17 February 1941, the Germans arrested Kolbe for the second time. He was imprisoned in the Pawiak prison in Warsaw, and on 25 May 1941 he was deported to Auschwitz. There, as a member of the secret organization of prisoners, he served as a confessor to his fellow prisoners and celebrated the Holy Mass.

At the end of July 1941, one of the prisoners from Maximilian Kolbe’s block escaped. The deputy commandant of the camp, Karl Fritzsch, ordered a roll-call and, in retaliation, chose ten prisoners whom he sentenced to death. One of them was Franciszek Gajowniczek, who, when chosen by the SS man, stated aloud: “How sorry I feel for my wife and children who will become orphans.” His words were heard by Father Maximilian, who left the ranks and stood before the German officer. “What does this Polish pig want?” Fritzsch growled. While they were searching for an interpreter, Kolbe tried to kiss Fritzsch on the hand and asked in German whether he could be taken instead of Gajowniczek. “I want to encourage others to live,” he said. Witnesses to this event reported that both the prisoners and the Germans were shocked. Everybody knew that the most severe punishment would be meted out for such audacity. However, Fritzsch agreed to Kolbe’s sacrifice.

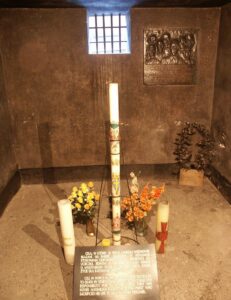

The ten convicts were locked in a basement without food or drink and one can only imagine their death in torment. Two weeks later, out of those locked in the cell, only Maximilian Kolbe remained alive. On the orders of the SS, he was then killed with a phenol injection. It was 14 August 1941, the eve of the feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The monk’s body was burnt in the camp’s crematorium. It is not known what happened to the ashes – they may have been dumped into a pond or scattered on farmland. A small chalice made of sheet metal and a missal that had been probably smuggled into the camp have been preserved. Today they are treated as his relics, and are carefully preserved in the church in Oświęcim.

In 1971, Pope Paul VI beatified him, and on 10 October 1982, Pope John Paul II included him among the holy martyrs of the Catholic Church. Franciszek Gajowniczek survived the war and died in 1995 at the age of 94.

Author: Piotr Abryszeński – PhD, employee of the History Research Office of Institute of National Remembrance

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin