On 17 September 1939, the Soviet Union, without declaring war and breaking the provisions of the non-aggression pact, entered the eastern territories of the Republic of Poland. As a result, Poland became the only country that had to face two invaders during the Second World War. What were the consequences of Soviet aggression? Could it have been prevented? We talked with Prof. Marek Wierzbicki from the Catholic University of Lublin.

Polish History Museum, Natalia Pochroń: Was it the fourth partition of Poland on 17 September 1939?

Marek Wierzbicki: You could say that. The Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact signed on 23 September 1939 by representatives of the Third Reich and the Soviet Union contained a secret protocol on the division of Eastern Europe into spheres of influence – German and Soviet. The line of this division ran almost through the center of the Polish state, along the rivers: Narew, Vistula and San. In this way, the Third Reich and the Soviet Union divided the territory of Poland among themselves, and the aggression of the Red Army of 17 September 1939 sealed the provisions of this pact and implemented them. So yes, we can definitely talk about another partition of Poland.

PHM: The secret protocol attached to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact defined the shape of the postulated boundaries of the sphere of influence. Did it mention invasion?

Marek Wierzbicki: No, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the protocol attached to it were in diplomatic language. The signatories of the agreement declared that “in the event of territorial and political transformations” in the territories belonging to the Baltic states and the Polish state, the zones of interest of Germany and the USSR will run along specific borders. Just this. There was no question of aggression and armed seizure of these lands, although it was obvious that this would happen. The agreement between the Soviet Union and the Third Reich was accompanied by a foreshadowing of a war in Europe, and the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact significantly accelerated it. Encouraged by the support of the USSR, Hitler decided to attack Poland on 1 September 1939. Stalin followed soon after.

PHM: Why did the USSR only attack on 17 September?

Marek Wierzbicki: According to the oral arrangements made between the two totalitarian states, the Soviet Union was to enter the war much earlier. Stalin, however, was very cautious and watched the turn of events quite closely. He wanted to check whether Germany would be able to defeat the Poles and whether Poland’s western allies – France and Great Britain – would take its side and intervene militarily. Today we know that, although [the countries] declared war on Germany, they did not take any specific military action. This encouraged Stalin. When he realized that France and Great Britain would not react militarily in Poland’s defense, and that Germany was advancing, he decided to join the war and enter the eastern territories of Poland.

PHM: When was the idea of aggression against Poland born in the USSR? Was it the result of the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact or maybe the idea had already appeared earlier?

Marek Wierzbicki: It had definitely appeared earlier. It was quite a long and complicated process, which had its origins in the Polish-Bolshevik war of 1919–1921. The Soviet elite was guided by the principles formulated by Lenin – the extension of the proletarian revolution to other countries in Europe and the world. When Poland managed to stop the Bolshevik revolution near Warsaw in 1920, the communists had to postpone the implementation of their imperialist plans. However, Lenin never gave up on it.

From the very beginning of his assumption of power, Joseph Stalin sought to extend the revolution, including by bringing about a war between the capitalist states and the overthrow of the order established by the Versailles Treaty after the First World War. It was also useful to the Germans, who felt disadvantaged by what they perceived as the unfair treatment they received at the hands of the victors. Due to these common aspirations, the USSR and the Third German Reich established a secret military cooperation as early as the 1920s.

PHM: It didn’t last long though? After all, the interests of these two countries with imperialist plans were incompatible in the long run.

Marek Wierzbicki: Yes, the situation changed in the 1930s when Hitler took power in Germany. Ideological reasons, including the Führer’s hostile attitude towards the communists and the entire USSR, caused the cooperation between the states to be suspended for several years. They took it up again in the first half of 1939. Then Hitler and Stalin recognized that despite their ideological differences, the alliance could serve their interests.

The German-Soviet cooperation was a huge surprise both in Europe and on other continents. Not only that – it was quite a shock also for the communists themselves. Until now, they had considered Nazi Germany as their main enemy, and then suddenly Stalin ordered them to cooperate with them. In the long run, the interests of both countries were indeed contradictory and irreconcilable. Stalin, however, approached this rationally. As I mentioned, the plan to extend the Communist Revolution was still in the back of his mind. Cooperation with Germany provided an ideal opportunity for this. He hoped that they would be able to overthrow the [post-war] Versailles order which would lead to the weakening of capitalist states – then he would join the war and achieve his goal.

Initially, everything was going according to plan. It soon turned out, however, that Germany was an obstacle to its implementation, and was starting to increasingly threaten Stalin’s imperialist plans. So he probably started to prepare for war. Hitler turned out to be faster, however.

PHM: Was it possible to predict the USSR’s aggression against Poland? Were there any signals pointing to the imperialist aims of the Soviets?

Marek Wierzbicki: The Soviet Union did everything to reassure international opinion and convince Western European elites that there were no imperial plans and that the Third Reich was the main threat to security in Europe. In order to make this narrative credible, he initiated various international agreements, and security treaties, and signed on for membership in international organizations. It was all supposed to hide his true intentions, and it must be admitted that, to a large extent, he succeeded. Even in Poland, which, due to its difficult experiences under the Russian partition and/or the war of 1920, had a certain prejudice against the Russians, the political elite were somewhat lulled by the Soviet propaganda.

PHM: Could they have done more to prevent this threat? Change their eastern policy?

Marek Wierzbicki: It’s hard to say. Today it is easy for us to talk about what could and could not be done, because we know how it all turned out and what the political elite of the time could not have known. The Polish authorities were focused on the aggressive policy of the Third Reich, which made increasingly bold claims to other territories. Soon the Third Reich also demanded the Free City of Gdańsk and the creation of an extraterritorial motorway in Poland. The Third Reich was the greatest threat to Poland at that time. Nobody expected that the Soviet Union was also preparing aggression plans against Poland.

PHM: Piłsudski had expected it – he repeatedly warned against the threat from the USSR. He believed that, despite the likelihood of an armed attack by the Third Reich, Poland should be more afraid of the Soviet Union because its aggression would not cause any reaction from Western countries.

Marek Wierzbicki: Yes. But when Piłsudski was alive, the policy of the Third Reich was a bit different. The period of the most aggressive German policy actually took place after his death in 1935. It was then that the Germans began to openly expand their military power and violate the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles. These actions drew the attention of most European countries, Poland was not the only country who noticed the growing threat posed by Germany. The Soviet Union remained in the background. Poland should have been tipped off by the fact that the two countries were brought closer together. It might have been surprising, but it was not secret at all.

Already on the second day after the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, British diplomacy and intelligence, followed by American, French and Italian, and even the governments of Estonia, Latvia and Japan, learned about the protocol itself and about the secret protocol containing plans for the division of Eastern Europe. However, nothing was done about it.

PHM: So Piłsudski was right.

Marek Wierzbicki: In a way, yes. The attitude of France and Great Britain towards the Soviet Union in the initial period of the war was quite ambiguous, as they did not react in any way to the aggression against Poland on 17 September.

PHM: The aggression against Finland in November 1939 met with a much more resolute reaction from the West. Where did this change come from?

Marek Wierzbicki: It is not entirely clear why the Western countries reacted just then, but the fact is that they responded with much greater determination. Only then did they recognize the USSR as the aggressor and kick them out of the League of Nations. At one point, they even considered sending an expeditionary force to Finland composed of British, French and Polish forces. Ultimately, however, the plans did not materialize, and after the capitulation of France in the battles with the Third Reich, the topic of any offensive actions against the Soviet Union completely disappeared. The conservative attitude of the Western allies to the USSR’s aggression against Poland is not surprising, however, the Polish government itself acted ambiguously.

PHM: Why?

Marek Wierzbicki: The Polish authorities were surprised by the Soviet attack. They did not expect it at all. At the same time, they realized that no matter how the situation in the eastern territories developed and what the Soviet Union’s intentions were, they were unable to fight on two fronts. It must be remembered that this is the sole instance in the history of the Second World War that one country was attacked by two armies, or, to be precise, by three armies. Slovakia also attacked from the south. Poland found itself in a trap.

In addition, the Polish authorities did not know what to think about the entry of the Red Army. The more so because Soviet propaganda proclaimed that the Soviets were coming to the rescue and defending the civilian population. Some even shouted that they were entering Poland to “beat the German.” This was all very confusing. As a result, the government decided not to declare war, or even to openly declare the existence of a state of war between Poland and the USSR.

PHM: In 1932, Poland and the USSR signed a nonaggression pact, which was finally extended until 1945. In light of this fact, how did the Russians justify their aggression against Poland?

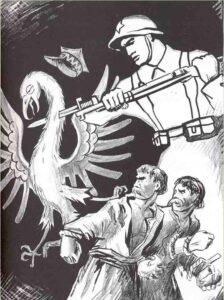

Marek Wierzbicki: At 3:00 in the morning, the Polish ambassador to Moscow, Wacław Grzybowski, received a note from Vyacheslav Molotov, the USSR’s minister for foreign affairs, stating that the Polish state had ceased to exist, so the Soviet troops were forced to enter Polish territory to defend the culturally close Belarusian and Ukrainian minorities. It was, of course, a lie – the Polish army was still resisting the Germans, and the Polish government was on the territory of its country. There was no question of any collapse of the Polish state. So Grzybowski didn’t accept the note, but it didn’t matter. The Soviet Union applied a fait accompli policy and a few hours later the Red Army entered Poland.

PHM: In an article published in 2020 in The National Interest, Putin stated that if the USSR had not taken half of Poland, “millions of people of different nationalities would be devoured by the Nazis and their local supporters – anti-Semites and radical nationalists.”

Marek Wierzbicki: Soviet propaganda argued that the Red Army was entering eastern Polish lands to protect the local Belarusian and Ukrainian population from both the Germans and Poles who threatened them. As you can see, the Russians use this narrative to this day – and not only in relation to the events of September 1939. They operate exactly the same now. It is enough to look at how Russia has justified the attack on Ukraine. Putin has argued that he must come to the aid of the civilian population and protect them from their own fascist government that is threatening their existence. Sounds familiar, right? The further pattern of action is also strikingly similar – mass terror, robberies, plunder…

PHM: Soviet propaganda also spoke about the enthusiastic welcome of the Soviet troops by the people living in the territories of today’s western Belarus and Ukraine. How was it really? How did the population react to the entrance of the Red Army?

Marek Wierzbicki: Reactions were varied. A large part of national minorities reacted favorably or at least neutrally to the Soviet aggression. This was largely due to the improper national policy of the Polish state before the war, which resulted in discrimination against national minorities. It also came from the economic conditions prevailing in these lands [at that time]. Let us remember that the eastern parts of the Second Polish Republic were mostly very impoverished, and inhabited by poor people who were discriminated against and exploited by the Polish elite. When the Soviet army entered these lands, they spoke of defending the poor and overthrowing the Polish lords, creating a state of workers and peasants, granting them political subjectivity, and introducing the principles of equality and social justice. Such slogans fell on fertile ground.

PHM: Probably not all of them – just look at the heroic defense of Grodno.

Marek Wierzbicki: Yes, the majority of the Polish population took a negative attitude towards the new government, expressing active or passive opposition. The best example is Grodno. For three days, the civilian population, together with the army, heroically defended the city against the attacks of the Soviet forces. Unfortunately, it was not possible to stop them. The consequences of the fighting were dire. After capturing the city, the Soviet political police shot three hundred defenders of the city – both soldiers and civilians. The same was done with everyone who resisted the Soviets. Any manifestation of resistance to the Red Army was considered counter-revolutionary activity and punishable by death. This did not apply only to Poles.

Although initially the Soviet authorities made some concessions to the Belarusian and Ukrainian people, it did not last long. The period of a certain empowerment of their culture ended with the ruthless Sovietization of these areas. These changes were accompanied by brutal repressions, arrests, deportations and mass murders. As a result, the majority of the population, who had initially supported the Soviet aggression, quickly changed their attitude.

PHM: Despite this, this aggression is perceived positively in Belarus today, and 17 September is celebrated there as the Day of National Unity.

Marek Wierzbicki: This is largely due to the policies of the current government in Belarus, which draws from the traditions and patterns of the Soviet state. For Belarusians, the aggression of the Soviet Union against Poland was an act of unification of the lands lost by them as a result of the Treaty of Riga in 1921. Therefore, they perceive this aggression positively and treat it as a national holiday. The situation is different in the case of the Ukrainians – most of them view the USSR’s attack on Poland rather negatively, which results from their own experiences. After a short period of Ukrainization in the south-eastern territories of the Republic of Poland, the Ukrainian population was subjected to brutal Soviet repressions. Activists of the Ukrainian national movement especially suffered . Ukrainians remember this and approach this aggression rather negatively, although they believe that it did increase the importance of Ukrainian culture.

PHM: What were the consequences of the USSR’s aggression on Poland?

Marek Wierzbicki: As a result of aggression against Poland and the other countries of Central and Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union significantly expanded its territory. Some of the lands they occupied were never returned to these countries. In addition, Stalin took control over some countries. Political elites who resisted the new government were murdered, and in their place a new authority, one subordinate to the USSR, was imposed. This is how Stalin indirectly implemented his plans for expansion into Central and Eastern Europe, making it independent from the union for nearly fifty years. It all started with the aggression against Poland.

PHM: Do we feel these consequences in some way also today?

Marek Wierzbicki: Definitely yes. We can see the most impactful of them by looking at the map – 52% of the territories lost by Poland have never been returned. To a large extent, these were lands that have been important for Polish culture and identity for centuries. As the Soviet Union found itself on the side of the victors of the Second World War, there was no question of their recovery. Admittedly, there were voices calling for a fight for lost lands – after the war, these ideas were particularly vivid among Polish emigrants. However, these were hopes that had no chance of being fulfilled. After the collapse of the USSR and Poland’s independence, the concepts expressed by editor Jerzy Giedroyc and the circles of the Paris-based “Kultura” were adopted. These stated that it was necessary to ensure reconciliation with the peoples of Eastern Europe and recognize their state-building ambitions, rather than fight to regain lost lands. And so it happened. We accepted the loss of these lands, although it was undoubtedly, and still is, a huge blow. As a result of this aggression, an important and long-term stage of Polish history irretrievably passed.

Interviewer: Natalia Pochroń

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin