On 27 March 1981, “Solidarity” organized a protest in response to the beating of union members by the militia. Their strike, with at least 2 and a half million participants, is also remembered as their largest protest.

by Tomasz Kozłowski

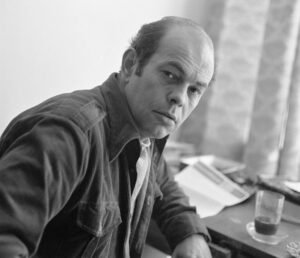

In February 1981, General Wojciech Jaruzelski became Poland’s prime minister. For over a decade, he had served as a member of the Political Bureau and as Minister of National Defense. He was also a close associate of Stanisław Kania, the first secretary of the Polish United Workers’ Party. Their political alliance endured throughout the 1970s and as Vitaly Pavlov, a KGB officer residing in Warsaw, recalled, the duo always “agreed on a plan of counteracting and [Kania] joined the action, with the support of General [Jaruzelski]”.

On 25 February 1981, Jaruzelski gave a speech calling for “90 peaceful days” – three months without protests or strikes. This was a clever bit of propaganda, as it presented Solidarity and the strikes as the main source of tension in Polish society. The government argued that this peace was necessary in order to focus on fighting Poland’s worsening economic crisis.. This appeal for peace had some chance of success, after all, these two leading figures of the new government were still able to inspire confidence among the public. Jaruzelski was a prime minister in uniform – and the army, although it was part of the communist system, traditionally enjoyed a certain status in Poland. In addition, Mieczysław Rakowski, as the deputy prime minister delegated to contacts with “Solidarity”, had been perceived as a liberal for years.

An attempt at coexistence

The main problem for the government was the two strikes that had been going on for several weeks: one by agricultural workers and the other student-led. Two days after the exposé, Deputy Prime Minister Mieczysław Rakowski met with the chairman of Solidarity, Lech Wałęsa. He assured him that the government would seek a compromise and that the agreement was in the interest of both parties.

Kania and Jaruzelski wanted to ease the tension in the country. This would curb internal party opposition demanding a confrontation with “Solidarity”, and perhaps even pacify Moscow, which was observing Poland’s “creeping revolution” with growing dissatisfaction. However, the government set itself one more secret goal – the army and the ministry of internal affairs were significantly accelerating preparations for martial law.

In truth, the protests were not proving useful to anyone involved. The chairman of “Solidarity” was not in favor of the “wild strikes” which were taking place without any agreement from the union leadership, and they were also exacerbating the situation in the country. Wałęsa even wondered if they were not intentionally organized in order to torpedo any possibility of an agreement with the government: “We have come to the conclusion that someone is trying to create conflicts which will distract us from our goal,” he explained to the head of the Press Office of the Polish Episcopate. “The purpose of all of this is to distract Solidarity from effective action.”

An agreement was finally reached following a result of a series of behind-the-scenes consultations attended by Wałęsa’s advisers (Bronisław Geremek and Jacek Kuroń) and government representatives (Mieczysław Rakowski and Stanisław Ciosek). The government approved the registration of the Independent Students’ Association, which ended student protests. Agreements were also signed with striking farmers, however, their trade union was not legalized by the government.

Wałęsa, pleased with the defusing of a potentially dangerous situation, explained during informal talks that the new government can “count on us because we [also] want peace.” The leadership of Solidarity and government and ministerial delegations were even getting ready to conduct joint consultations on reforms addressing various problems from the economy to the judiciary.

Murmurs from the East

On 4 March 1981, a few days after the strikes had ended, a Polish delegation headed by the First Secretary of the Polish United Workers’ Party, Stanisław Kania, and Prime Minister Wojciech Jaruzelski, went to Moscow. They met with Leonid Brezhnev and several other members of the Soviet Politburo. The Polish delegation did not hear any words of appreciation for ending the strikes. From Moscow’s perspective, it looked like another victory for Solidarity. Leaders of the USSR, East Germany and Czechoslovakia feared that the Polish revolution would spread to the entire Eastern Bloc. For them, the best solution was to force the Polish authorities to introduce martial law.

Under pressure, Kania and Jaruzelski decided to change their tactics. First, they decided to target the most famous members of the democratic opposition – Jacek Kuroń and Adam Michnik, who were active in the Workers’ Defense Committee. Immediately after returning from Moscow, Stanisław Kania suggested launching the offensive. The Minister of Internal Affairs Mirosław Milewski readily agreed to this: “I inform you that Kuroń was summoned to the prosecutor today – since he refused to come, he was escorted.”

For Moscow, the issue of legalizing agricultural trade unions was also particularly important. Also in this case, as Kania expressed to Brezhnev: “It should not be possible in any way for the Rural Solidarity to create a union.” The Minister of the Interior applauded him again. There were many people among the leadership of the Polish United Workers’ Party, the army and the Security Service who expected a shift in politics and a radical crackdown on Solidarity. One of them was General Mirosław Milewski.

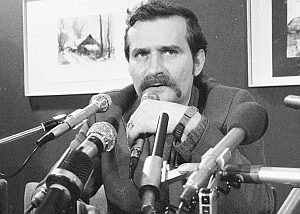

On 10 March 1981, Jaruzelski met with Wałęsa. He mentioned international pressure, economic problems and the need to temper the activists of the democratic opposition. Wałęsa agreed that the prime minister was right. He still believed that Solidarity must strive for an agreement with the government. “Mr. General, as a reasonable person I am going with you,” Wałęsa said, “I’m going with you because I know that I will have no one else to go with.”

A day later, Wałęsa was in Gdańsk. He mentioned his talks with the prime minister and expressed his disappointment with the fact that further protests had broken out in the country. He emphasized that the recent agreements with students and farmers should be seen as an achievement, even though they had come under criticism: “We are moving further and further from what we assumed, we are going more and more in a dangerous, very dangerous direction. I do not wish to scare you, because I am not afraid, but I am afraid of responsibility for the state, for other people.” Not everyone shared Wałęsa’s fears.

Collision course

On 12 March 1981, a strike began in Bydgoszcz, which a few days later turned into the occupation of the local headquarters of the authorities of the United People’s Party – an organization of peasants linked to the communist party. Several dozen farmers, led by, among others Roman Bartoszcze demanded the legalization of agricultural trade unions. They were supported by the local “Solidarity” led by Jan Rulewski.

The authorities of the communist party were not ready to make another concession to the strikers. Kazimierz Barcikowski informed other members of the Political Bureau that if the talks with farmers did not bring results, “the secretary of the United People’s Party will appeal to the authorities for help in stopping the occupation of the building.” Stanisław Kania did not want to show any weakness either, stating “Bydgoszcz is a new attempt to bring the authorities to their knees.” General Milewski reacted to his words: “If yesterday the authorities were asked to remove the occupants of the building, it could have been done without any problems. With each passing day the support grows for them [i.e. strikers] and it will be more difficult.”

It was evident that the balance was tilting towards the supporters of an uncompromising crackdown on the strike. This was due to the fact that work on the preparation of the martial law was slowly coming to an end. The Russians were also well informed. On 16 March 1981, maneuvers by the Warsaw Pact troops “Soyuz-81” began in Poland. On this occasion, Marshal Viktor Kulikov passed a message to Kania and Jaruzelski from Brezhnev. Once again they heard accusations of being too lenient towards “Solidarity”, and the leader of the USSR also mentioned the need to introduce martial law.

On 19 March 1981, a meeting of the leadership of the Ministry of the Interior was held. General Bogusław Stachura was informed that about 1,500 militia men were deployed in Bydgoszcz. General Adam Krzysztoporski, the head of the secret police and one of Stanisław Kania’s aides, stated: “Mediation projects do not promise a change in the situation in Bydgoszcz, so the intervention of our forces must be taken into account. Otherwise, one has to accept the fact that Rural Solidarity will be registered “. Meanwhile, Jan Rulewski, the head of the Bydgoszcz “Solidarity”, decided that day to raise the issue of farmers at the session of the Provincial National Council, i.e. the local government.

The delegation of trade unionists and farmers led by Rulewski was not allowed to speak, so they began to occupy the hall. In the evening, militia men stormed the building and forcibly removed those remaining in the room. Rulewski, Bartoszcze and Łabentowicz, who were injured during the removal, were taken to the hospital. The background of the decision to intervene is not fully explained – there is no trace of discussion on this topic in any documents.

This fact inspired conspiracy theories about this event over the years. Some activists of “Solidarity”, and years later also journalists and historians, claimed that it was a deliberate provocation by some employees of the Ministry of the Interior. It has been suggested that perhaps the entire operation took place in agreement with the Kremlin. This seems unbelievable. The preserved documents indicate instead a certain automatism of action and a lack of imagination.

On 24 March 1981, during a meeting of the Political Bureau, Stanisław Kania stated that “the operation in Bydgoszcz did not take place without our knowledge,” indicating that the decision was approved by the Politburo, or at least no objections were raised. Years later, Kania and Rakowski agreed in a private conversation that Jaruzelski had made the decision. In their opinion, the militia was to escort or carry out the protesters, and there was no question of any violence. Whatever the case, attempts were made to avoid confrontation until the last moment.

Minister Stanisław Ciosek called Lech Wałęsa that day. Karol Modzelewski, the union spokesman at the time, heard the conversation: “Ciosek, usually very stable and balanced, was clearly nervous this time.” He said that it was absolutely necessary to influence Rulewski to make him leave the occupied building. “You have to call them and try to persuade them to leave the building,” Ciosek pleaded, “Believe me, it is very important and very urgent.” Wałęsa did call Rulewski and persuaded him to end the protest, but he was unable to convince him to leave. At the end of the conversation, Wałęsa said, “You’re the chairman there. It’s your responsibility. I would have walked out of there.”

Confrontation

Everyone held their breath – the violent beating of three activists, including the president of the region, was like declaring war on “Solidarity”. Information about what happened was passed on from mouth to mouth, and later reported in the press and leaflets. For example, it was repeated that Rulewski’s teeth had been knocked out and others were mistreated.

The reality was a little different. Years later, Rulewski admitted that he was hit, but his teeth were not knocked out – only his prosthesis fell out. Michał Bartoszcze suffered a heart attack, which was the result of stress. The screams and accusations of beatings were a psychological play. Nonetheless, it was effective – these events caused a gigantic political crisis.

There was a change in rhetoric among the party leadership. People who had tried to communicate with “Solidarity” previously – Kania, Jaruzelski and Rakowski – were now claiming that the union was a threat. Jaruzelski explained during a meeting of the Politburo: “For several months we have been more and more fully aware that part of the ‘S’ is steering towards taking power. We had no illusions for a long time, but we counted that our economic, political, party and propaganda activities would effectively limit the “S”. That’s why we made compromises.” At the same time, he emphasized the high costs of introducing martial law: “Before making final decisions, we must be fully aware that a violent solution cannot be maintained within a certain framework. I can see we’re getting closer to it. That is why I emphasize once again that we must try by all means not to go to the extreme.” Moderate bureaucrats were humiliated by the failure of their conciliatory policy. The secretary and the prime minister feared criticism from radical members of the party leadership, the army and militia, and from Moscow.

The national authorities of Solidarity also could not remain deaf to the outrage of rank and file members of the union. The tool of defense was a warning strike carried out on 27 March 1981 between 8.00-12.00. Over 2,600,000 Poles took part in it. The largest plants in the country joined the strike, all communication stopped, and not only universities, but also schools protested. In some regions, strikes were rife. It was the peak moment of the mobilization of “Solidarity”. The strike gave Lech Wałęsa and his advisers an advantage in testing the government’s position. Especially since a general strike was scheduled for March 31.

Both sides sat down again for talks on 30 March 1981. Representatives of the authorities, frightened by the scale of social mobilization, were more willing to make concessions, for example in the matter of explaining the circumstances of the beating and bringing the guilty to justice. On the other hand, they threatened with the consequences of a further escalation of tension. Tadeusz Mazowiecki, one of Wałęsa’s closest advisors, recalled his conversation with Mieczysław Rakowski years later. The deputy prime minister told him that there might come a moment “when we will not be both interned [with Rakowski], but both of us will be smoked” By implication: by Moscow or party hardliners.

Ultimately, both sides reached a compromise known as the Warsaw Agreement [or: Warsaw accord]. The government undertook to “fully present the events in Bydgoszcz on television by representatives of Solidarity” and to conduct a thorough investigation observed by representatives delegated by the union. Changes in the binding law were also promised in order to meet farmers’ demands. In return, the leadership of “Solidarity” canceled the general strike planned for 31 March.

A free fall

Many Solidarity activists did not consider the agreement a success. Karol Modzelewski noted that the warning strike on 27 March 1981 was the moment when “Solidarity was at its peak, and the ruling camp was losing the support of its own base and was politically abandoned. It was the climax of the revolution.” In his opinion, for trade unionists “preparing for the greatest battle of their lives, the demobilization order [i.e. cancellation of the general strike] must have been a shock, especially since the decision was made behind their backs.

Although the situation eventually calmed, these events seem to have ended any possibility of coexistence between the trade union and the authorities. The efforts of some party leadership to reach an agreement, even at a high price, proved ineffective and the conclusion of another agreement only raised further concerns in the Kremlin. Leonid Brezhnev attacked Kania: “How many times have we tried to convince you that drastic measures must be taken and that you cannot compromise with Solidarity endlessly? Do you repeatedly speak of the path of peace without understanding or wanting to understand that the “path of peace” you are walking is paid for with blood?”. Defense Minister Dmitry Ustinov feared that the Polish communists might lose power: “I think bloodshed cannot be avoided. It will happen. And if someone is afraid of this, then of course they will have to constantly give up their position. And all the gains of socialism can be lost this way. “

In the following months, the leaders of the Warsaw Pact countries began to put even more pressure on the imposition of martial law in Poland and actively supported the internal party opposition to Stanisław Kania. The government finally veered from the path of compromise. Meanwhile, “Solidarity” was crippled from the confrontation. The cancellation of the general strike caused the social movement to slowly demobilize. In August 1980, 700,000 people went on strike. In the first strike of “Solidarity” in October 1980 – even 1.3 million. The protest action after the beating in Bydgoszcz – in which 2.6 million people participated – was, however, the last great insurgency.

Author: Tomasz Kozłowski – PhD in political sciences, employee of the History Research Office of Institute of National Remembrance

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin