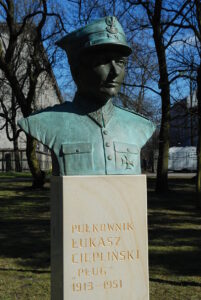

The anniversary of his death has been recognised as a day to commemorate the ‘cursed soldiers’ who fought against Soviet occupation after the end of the Second World War. However, Łukasz Ciepliński still appears to be a little-known, if not to say forgotten, figure.

by Grzegorz Wołk

‘I am glad I will be murdered as a Catholic for the Holy Faith, as a Pole for my homeland, and as a man for truth and justice,’ Ciepliński wrote from his death cell. When he was being executed on 1 March 1951, he was at the head of an underground organisation, which was to replace the Home Army and, based on the structures of the Polish Underground State, counteract the strengthening of Soviet power in the country. At the time, he was the most important figure of the anti-communist underground in Poland, which functioned in spite of brutal repressions.

Youth and the army

Many future officers of the Polish Army in the interwar period originated from patriotic families, in which a military career was welcomed. This was no different for the Ciepliński family. Łukasz was born in 1913, in Greater Poland, under Prussian rule at the time. His older brothers had taken part in the Greater Poland Uprising, owing to which the region had become part of Poland. His father owned a bakery and ran a shop with colonial goods. The young Łukasz Ciepliński could therefore enjoy a stable childhood, even though his family was very large (he had seven siblings). As early as primary school, he was described in similar terms: balanced, polite, smiling, a top student.

At the age of sixteen, he entered the elite Cadet Corps No. 3 in Rawicz. This was a secondary school where future Polish Army officers were educated. After passing his maturity exam in 1934, Ciepliński continued his education at the three-year Infantry Officer Cadet School. It was there that he attained the rank of officer and – as proof of his outstanding skills – and high standing among the students, he was chosen to represent his class during a meeting with President Ignacy Mościcki. After graduating, second lieutenant Ciepliński was assigned to the garrison in Bydgoszcz where, in 1938, he was promoted to commander of the anti-tank company of the 62nd Infantry Regiment.

Against Hitler’s army

Ciepliński’s unit was intended to fight in the first line, should war break out with Germany. From the first days of September 1939, the Regiment took part in battles with the Wehrmacht, and also experienced the shelling carried out by German saboteurs. However, the unit managed to withdraw smoothly, and avoid being broken up. The Regiment reinforced the northern flank of the Polish Army in the Battle of the Bzura, which proved the greatest battle of the September Campaign.

Ciepliński performed an extraordinary deed at that time: he managed to destroy several German tanks, and a successful fire from the anti-tank cannon of which he became a gunner, temporarily stopped the enemy’s attack. He was then promoted to Lieutenant, and awarded the Cross of the Order of Virtuti Militari, the most important Polish combat distinction. The effectiveness of the firing was no coincidence. In 1938, when a shooting competition was organised in Ciepliński’s home garrison, his platoon won with 87% accuracy.

However, in September of 1939, German superiority was too great to mount an effective defence against it. Ciepliński’s unit lost many soldiers in combat, but its survivors successfully made their way to Warsaw. They strengthened the defence of the capital, and, after its capitulation, the young lieutenant luckily avoided captivity. Together with his commanding officer, he decided to make his way to Rzeszów. This was justified, as the Germans were looking for Polish officers serving in Bydgoszcz, wanting to take revenge for their fight against sabotage operations carried out by the local German minority.

In wartime conspiracy

In German- and Soviet-occupied Poland, various conspiratorial organisations began to emerge rapidly. They were created mainly on the basis of Polish Army officers who had escaped captivity. They attempted to cover as much of the country as possible. Ciepliński – delegated to this task by his former commander – was in charge of creating the White Eagle Organisation network in Rzeszów.

The White Eagle Organisation was created in September 1939 by Colonel Kazimierz Pluta-Czachowski, a true veteran of the struggle for independence, who had already been involved in it before the outbreak of the First World War. Members of the White Eagle undertook diversionary operations, but their main field of activity was the organisation of intelligence networks, and conducting propaganda actions against the occupier. In June of 1940, the organisation became part of the Union of Armed Struggle, the main conspiratorial structure subordinated to the Polish Government-in-exile. Ciepliński did not stay in Rzeszów for long: towards the end of 1939, he was in a group that crossed the Hungarian border. There, he reported to the Polish consulate. The Hungarian authorities, then in a political and military alliance with Germany, often turned a blind eye to underground Polish activity on their territory, and Budapest became an important place for underground couriers.

Lowdown; CC BY-SA 3.0)

In Hungary, Ciepliński and a group of other officers were quickly trained in the principles of conspiratorial activity, and, in January of 1940, returned to occupied Poland. However, just after crossing the border, he was betrayed, and fell into the hands of the Ukrainian militia collaborating with the Germans. He was taken to the local Gestapo station, from where he managed to escape after three months, and reached Kraków. Provided with new documents and a fictitious identity by local conspirators, he returned to Rzeszów, where he took command of the intelligence network: not long before, his predecessor had been arrested and murdered by the Germans.

He managed to lead the Rzeszów network until the end of the German occupation, avoiding major incidents. The network under his command survived the occupation in good condition. In 1944, Pług (meaning Plough), as was his adopted wartime codename, had about 15,000 soldiers under his command. He could also boast of tangible intelligence successes. His subordinates managed, among other things, to get hold of parts of the V-2 rockets being tested at the nearby training ground, and, earlier, they collected evidence of an attack on the USSR being prepared by the Germans.

Throughout this period, he also prepared his subordinate units for the general uprising. For this purpose, military cadres were trained, and weapons procured and manufactured. In 1944, when Polish civilians were being murdered by partisans of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, he ordered the ‘Tit for Tat’ operation, which was intended to stop further murders of innocent civilians.

As the front and the Red Army approached, Ciepliński formed the 24th Infantry Division, which supported the Soviets during battles. Ciepliński’s subordinates took part in the battle for Rzeszów, and, after it was captured, they organised a militia and civil administration there. This state of affairs did not last long, however, as Stalin recognised Poland as his own sphere of influence, where he was installing an administration that was loyal to him, and comprised of communists. Members of the Home Army, such as Łukasz Ciepliński, faced repression or death at the hands of the NKVD.

For freedom and independence!

Seeing what the Soviets were doing, Ciepliński reorganised those subordinated to him. They continued to liquidate informers, this time Soviet ones. They also carried out operations limiting the size of forced conscriptions to the communist army. The most spectacular campaign, however, was an attempt to rescue Home Army soldiers from the largest prison in the region, who were awaiting transportation to Siberia. Unfortunately, the attack carried out in October 1944 ended in failure. The advantage of the Soviets and the Polish communists collaborating with them was so great, that Home Army structures were constantly being broken up by arrests. Armed resistance ceased to make any sense.

In January of 1945, The Home Army was disbanded, but its command formed the NIE organisation (meaning ‘NO’), which was to oppose the new occupation of Polish territory. Based on a trusted group of conspirators, a new network began to be organised. Ciepliński, promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, became Chief of Staff of the Krakow District in the spring of 1945.

Seeing the growing disproportion of forces, and the futility of armed struggle, the newly created conspiratorial structures were to operate without violence. In practice, however, this was very difficult. Arrests, deportations deep into the USSR, and the brutality of the new occupier, very quickly led to the forests being filled with new partisan units. This was the tragic fate of people fighting for several years against the German occupation. Instead of appreciating them after the war, the communists accused them of… collaboration with the Nazis.

President

In December 1945, Ciepliński was promoted to local president of the Freedom and Independence organisation (Polish acronym ‘WiN’), which replaced the dissolved NIE. He was then responsible for the whole of northern Poland. At that time, the WiN leadership believed that the only way to improve the situation in Poland was for the anti-communist parties to win the elections. They deluded themselves that Stalin’s promise to the Allies would not be broken, and they could count on fair suffrage. Time has shown that they were wrong. The communists rigged the elections, and representatives of legal opposition parties began to be persecuted and even murdered. WiN activists were also arrested. Fortunately, Ciepliński managed to hide successfully.

From December 1946, based on his wartime contacts, he began to build up a new WiN network. After subsequent arrests, he became the next president of what was already the fourth board of this organisation. He lived in Upper Silesia, where, as Marian Kaczmarek, he ran a shop selling fashion accessories. He managed to set up new smuggling routes, which allowed underground members of the organisation and couriers to reach the West. However, seeing the weakening will of resistance in society, and the lack of reaction of Western countries to the Sovietisation of Poland, he decided to suspend his activity in October of 1947. A month later, he was arrested.

A tragic end

The communist penetration of the independence underground was extremely effective. Apart from Ciepliński, at the end of 1947, almost the entire fourth board of the WiN, and the local presidents, were arrested. They were subjected to brutal torture. Ciepliński was mistreated and, on more than one occasion, carried unconscious from interrogation. ‘During the investigation, I lay battered in a pool of my own blood. My mental state under these conditions was such that I could not be aware of what the investigating officer was writing,’ he complained during the trial.

In spite of this, he conducted himself with dignity, aware of the fate that awaited him. His secret prison messages addressed to his wife and son Andrzej have been salvaged. They expose Ciepliński’s extraordinary willpower and deep patriotism, although he was not able to enjoy family life for long. He did not marry until August 1945, and, soon afterwards, left for Zabrze, where he ran his shop under a fictitious name. Two years later, his only son was born. The secret messages, written over a period of almost five months, were a very intimate farewell to his loved ones, and also the questioning of the sense of his struggle. ‘Will our sacrifices not be in vain, will unfulfilled dreams rise from their graves, will Andrzejek continue to follow his father’s ideas? I believe that they will not be futile: the dreams will rise, the son will replace his father, the homeland will regain its independence.’ Only one of his secret messages reached Ciepliński’s wife before his death. The others, although likely not all, reached his widow several years later.

The trial of the fourth WiN board itself was conducted according to Soviet standards, with no explanations by the defendants being taken into account. Accusations of collaboration with the Nazis must have been particularly painful for participants in the anti-Hitler conspiracy. The verdict came quickly. On 14 October 1950, Ciepliński was sentenced to death three times. Six of his closest associates died along with him. The positions of the murdered independence activists were taken by agents of the Ministry of Public Security. They created what is known as the fifth WiN Command, owing to which the communists could play an effective game with Western intelligence for several years.

Shot dead, Ciepliński was buried in an unknown location. He had told his cellmates that, before the execution, he would place a holy medal with the image of the Virgin Mary in his mouth. Exhumation work currently being carried out in Poland has made it possible to establish the identity of many nameless victims of Stalinism. Unfortunately, the skeleton with the silver holy medal has not yet been found.

Author: Grzegorz Wołk