Leopold Tyrmand was one of the most interesting figures of post-war Poland’s artistic milieu. Despite the oppression of the communist regime, he had his own way of opposing the system.

by Piotr Bejrowski

Tyrmand’s biographers aptly point out that he opposed communism not only ideologically, but also aesthetically. He wanted to maintain the continuity of Polish culture and tradition, noting that communism disrupted the development of a centuries-old civilization.

Tyrmand was born on 16 May 1920 in Warsaw to an assimilated Jewish family. In the late 1930s, he began studying architecture in Paris. The outbreak of the Second World War found him back in Warsaw. From there he travelled to Vilnius within the Soviet occupation zone. There, for a short time, he even wrote for the communist newspaper, which he later tried to conceal. Finally, he began collaborating with the underground movement, as a result of which, in April 1941, he was arrested by the NKVD and sentenced to eight years in prison. Two months later, however, the German-Soviet War broke out, as a result of which he managed to escape from prison. He managed to get false French documents, and he was not exposed, but his plan to get to France failed. Until 1944, he stayed in the Third Reich, where he worked, among other jobs, as a physical worker, a translator and a waiter. At the end of the war, however, he was sent to a concentration camp in Norway. For a year after the war, he continued working in Scandinavia, and after returning to Poland, he began working for the press and in the Polish Radio.

He concealed his Jewish origin, even from his wife and friends. After the terrible experiences Polish Jews had experienced during the German occupation, he tried to cut himself off from his past, which some of his friends ascribed to his war trauma.

Tyrmand hated communism. He manifested his dislike in his own way – by emphasizing his distinctiveness. He hated the gray nature of the communist system, its hypocrisy, uniformity and the need to adapt to prevailing rules. He would wear colorful clothes, try to speak differently and would raise unusual topics in conversation with other writers. Some regarded him as an arrogant snob, and others as an outspoken writer who was not afraid to say what he was thinking. He was an individualist who stood out against submissive milieu of other writers.

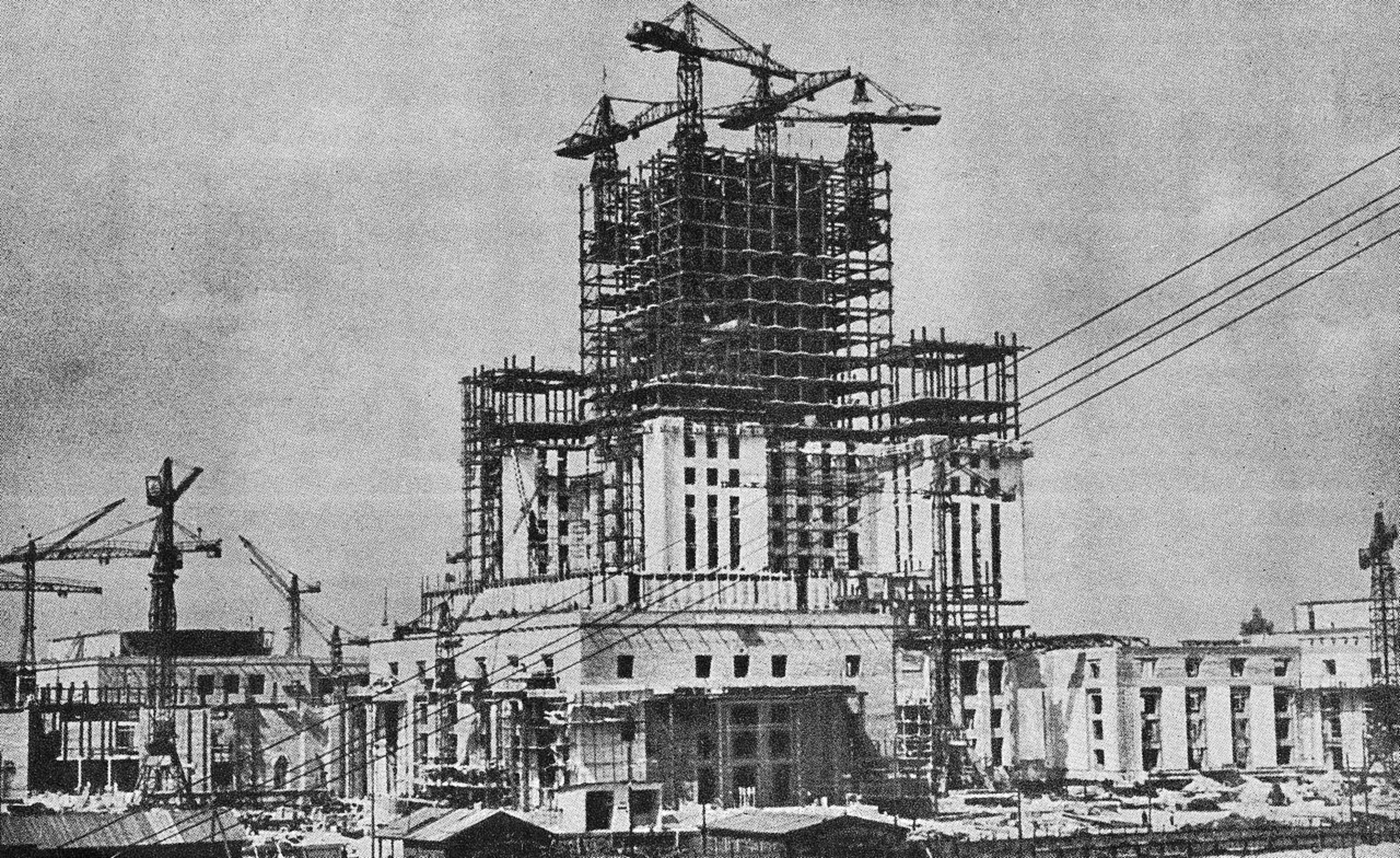

His trouble with censorship began in 1950, when, in a press report from a boxing tournament, he dared to criticize Soviet judges for having been biased. Subsequently, he was removed from the editorial office of the Przekrój magazine. Stefan Kisielewski, a writer and composer, helped Trymand by introducing him to the editorial board of the relatively independent magazine – “Tygodnik Powszechny”. However, the communist authorities also decided to close it down in 1953 for refusing to publish Stalin’s obituary. Thus Tyrmand was left jobless again. At that time he started writing a diary. In total, it covers only three months (from January to April 1954). Nevertheless, it includes a vast panorama of social interactions, the reconstruction of Warsaw after the war, as well as an insightful portrait of the cultural milieu. There was also a critical commentary on the reality of Stalinist Poland, a critique of its social and economic reality, and at the same time a manifestation of Tyrmand’s independence and a defense of individualism. It was not published until 1980 in London as Dziennik 1954 (Diary 1954).

Tyrmand stopped writing his diary when he unexpectedly received an offer to write a crime novel. The result of this work was his most famous novel titled Zły (published in English as The Man With White Eyes) published in December 1955. The novel takes place in Warsaw in the 1950s. Tyrmand elaborates on the city’s a criminal underworld, and its title, which means “Evil Man”, is a man who declares war on criminals. The book was enthusiastically received by readers, not least because it offered a contrast to mass-produced socialist realist literature. Despite showing the dark side of the city during Stalinism, communist censorship agreed to its publication.

Tyrmand’s popularity led him to develop other interests. He became a pioneer of jazz music. Although he could not play an instrument, he is still considered a legend of Polish jazz. He arranged numerous festivals and concerts, and also supported the activities of young jazz players. In the mid-sixties, he decided to emigrate. Thanks to a scholarship from the State Department, he finally settled in the United States. He quickly became a recognizable figure thanks to articles published in The New Yorker and The New York Times. Tyrmand criticized contemporary pop culture as a tool to destroy traditional values. While, in his opinion, popular culture in Poland under the communist regime was an antidote to gloomy reality, he also claimed that in the free world it contributed instead to the deprivation of young people.

On 19 March 1985, he died of a heart attack in Fort Myers, Florida. By virtue of a resolution of the Sejm of the Republic of Poland, 2020 was announced the year of Leopold Tyrmand.

Author: Piotr Bejrowski

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin