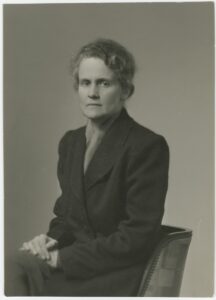

Countess Karolina Lanckorońska is best known for her memoirs titled Those Who Trespass Against Us: One Woman’s War Against the Nazis (‘War Memoirs’ in Polish). In the memory of Polish historians, whom she often generously supported, she went down in history as a scholar and patron of science. She was the first woman in Poland to receive a habilitation in art history.

by Marcin Wilk

The first female docent

Countess Karolina Lanckorońska of Brzezie (coat of arms Zadora) was born in Buchberg am Kamp in Lower Austria on 11 August 1898. Her father, Count Charles Lanckoroński, owned vast estates in eastern Galicia (Rozdół), the Kingdom of Poland, and Styria. He was also an influential figure at the imperial court. He sat on the Chamber of Lords and was Grand Mayor at the court of Franz Joseph I. Taking an active part in public life, he focused mainly on cultural matters. For years, he was involved in the restoration of the Wawel Castle.

He was an outstanding collector and art expert, who also belonged to the wealthiest people in Galicia. He inherited a rich collection of works of art from his ancestors – including works from the former collection of King Stanislaus II Augustus – and he amassed many works himself, including 14th–16th-century Italian paintings. In the 1990s, he placed his collection in a purpose-built Neo-Baroque palace (destroyed during the Second World War) at 18 Jacquingasse Street in Vienna, known at the turn of the century as the ‘Lanckoroński Palace’.

In his youth he travelled a lot, mainly around the continent, also along the Mediterranean Sea. His spectacular expeditions included a trip around the world. A trace of this escapade was his memoir Naokoło ziemi 1888-1889. Wrażenia i poglądy [Around the World 1888–1889. Impressions and Opinions], published in 1893.

He was particularly fascinated by Italy and Italian art. He instilled this love in his daughter, as well as passing on to her a love of knowledge and learning. He himself surrounded himself with books and left behind a rich library. As Karolina Lanckorońska expressed it, he had an ‘electronic’ memory.

According to Lanckorońska’s own accounts, she had much worse relations with her mother, Margarethe, Duchess von Lichnowski, Karol’s third wife. The Prussian-Silesian aristocrat communicated with her daughter in German. Meanwhile Karolina, although educated in Vienna, felt closest to Poland. The countess’s siblings, Antoni and Adelajda, were brought up in a similar spirit. During summer breaks from school, Karolina enjoyed going to the family estate in Rozdół, where she could admire paintings by Jan Matejko or Jacek Malczewski.

From an early age, the countess intensely developed her aesthetic and academic interests. During her studies – from 1920 onwards – in Art History at the University of Vienna, under the guidance, inter alia, of her master Professor Max Dvořák – she travelled all over Europe, mainly in order to acquaint herself with the art and culture of the antiquity, the Renaissance, and Baroque.

After completing her doctoral dissertation in 1926 on Michelangelo’s interpretations of The Last Judgement, she went for a longer period of time to her beloved Rome, where she researched the art of the Italian Renaissance and Baroque. She worked as a librarian at the Scientific Station of the Polish Academy of Learning, putting in order the library and photographic collections donated by her father. Following the death of Karol Lanckoroński in 1933, she settled in Lwów, occupied with managing the family legacy together with her siblings. She continued her research and teaching activities, and was involved in the organisation of academic life at the local John Casimir University. For some time, she chaired an organisation aiding female students.

A significant event – not only in her personal scientific biography – was obtaining her habilitation in Art History in 1935. She was the first woman in Polish academia with the title of docent in this field. Her dissertation was devoted to the decoration of the Il Gesù Church against the background of the development of Baroque in Rome.

A witness

Although the world war found her in Rome, Lanckorońska almost immediately decided to return to Lwów. She devoted Those Who Trespass Against Us (published in Polish in 2001), written immediately after the end of the war, and published over half a century later, at the end of her life, to the dramatic events of that time. The book, beginning with the memorable scene of a shopping trip, almost immediately became a bestseller. It also brought Lanckorońska, among others, a nomination to the most important Polish literary award, the ‘Nike’.

Lanckorońska was still teaching at the university in late 1939 and early 1940. However, she soon joined the underground movement. In January 1940, she took the military oath as a member of the Union for Armed Struggle. Numerous arrests hastened her escape from Lwów to Krakow, which she managed to reach thanks to false documents. She translated agitational materials for German soldiers into German, among other things. As a nurse, she helped in the work of the Polish Red Cross. The Central Welfare Council then entrusted her with the care of prisoners in the General Government.

In the first half of 1942, when she was coordinating the organisation of aid in Stanisławów (presently Ivano-Frankivsk), her activities aroused the suspicions of Hauptsturmführer SS Hans Krüger. Lanckorońska was arrested and placed in prison. During the interrogation, Krüger – upset by the countess’s unyielding attitude, and certain that she would be sentenced to death – revealed that he had murdered university professors in Lwów. She thus became a witness to the crime. In the meantime, the intervention of the Italian royal family with Himmler himself overturned the death sentence.

During one of her subsequent interrogations, this time in Lwów prison, she shared her knowledge of Krüger’s crimes with SS Commissioner Walter Kutschmann. Her report, which reached Himmler, was the reason for her continued imprisonment. With the number 16076, she was incarcerated at Ravensbrück camp in January 1943.

In spite of meticulous accounts and descriptions, we still do not know all of the details of her daily life and relationships with others. According to the historian and student of Lanckorońska, Teresa Chynczewska-Hennel, many of the memory images of that time were too drastic and horrifying to be included in a memoir. In describing that period, the author of Those Who Trespass Against Us admits, however, that, at one stage, she could enjoy incomparably better conditions than the remaining prisoners. For example, at Ravensbrück, she was entitled to medical care, better food, German newspapers and books, as well as walks. From the descriptions in Those Who Trespass Against Us, it appears that she had the opportunity to pursue intellectual work as well. She was also involved in the education of her fellow prisoners. In Ravensbrück, she secretly presented lectures on art history to educate women undergoing pseudo-medical experiments.

Professor Carla

Elżbieta Orman, a historian and researcher of Lanckorońska’s life and work, emphasises her characteristic strive to educate everyone ‘who ever came within her reach’. What was called ‘energetic pedagogy’ was – alongside research into history of art and science, to which Lanckorońska devoted herself – the driving force and flywheel of her post-war activity. Released from the camp, owing to the intervention of Professor Carl Burckhardt, President of the International Red Cross, she was soon offered a professorship in Fribourg, Switzerland. However, she did not accept the position, the main reason for this being – as she explained at the end of her life to her friend, art historian Lech Kalinowski – the specific environment. ‘Sir,’ she said, ‘I wanted to teach young Polish art historians. I wanted to teach Poles, and who would I teach in Fribourg? Italians, Germans, and the French.’

Still in 1945, she joined General Anders’s 2nd Corps. As an officer, with her usual vigour, she took up educational work among the Polish soldiers, who did not wish to return to the communist country. Lanckorońska took special care of volunteers from the Women’s Auxiliary Service. One of the participants recalled her as follows: ‘I don’t think you can say of her that she was lovely and warm. You did not go to her for gossip. (…) But if any of us had a matter requiring practical help, we would go to Carla assured that she would tackle the problem with great energy.’

In 1945, Lanckorońska founded the Polish Historical Institute in Rome together with Father Walerian Meysztowicz. As part of the scientific activities of this unit, from 1954, the annual Antemurale (28 volumes) was published, and from 1960 – Elementa ad Fontium Editiones (76 volumes), which – in line with Lanckorońska’s intention – contained source materials on Polish history from foreign archives, generally either barely or completely inaccessible to the majority of researchers in Poland. Almost simultaneously alongside the dissolution of the Polish Academy of Learning, the Roman Historical Institute – according to Mieczysław Zlat – in its own way took over the tasks performed during the Second Republic by the Roman Station of the Polish Academy of Learning.

Assistance for Polish researchers was also provided through the Lanckoronski Foundation, based in Switzerland. The Foundation was established in 1967 out of the transformed Karol Lanckoroński Fund. Among the foundation’s most important activities is the support of Polish historians and scientific research. Publications and queries are also subsidised.

A special type of support by the Lanckoroński family was its assistance during martial law. Karolina Lanckorońska sent, via befriended researchers and scientists, medicines and articles that were difficult to obtain or not available in Poland at all. This assistance was particularly important in Poland before 1989, when the country was struggling with a number of shortages.

Royal gifts

From the descriptions of Lanckorońska’s students and co-workers emerges an image of a woman devoted to science, consistent, strong, efficient and helpful, but also strict and demanding. However, not much is known about her personal life. Despite considerable solitude, she maintained an extensive correspondence with colleagues and friends from all over the world. She did not cease this activity in spite of the failure of her sight and hearing with age. Active until her final days, she did not give up her work and published regularly in Tygodnik Powszechny. It is said that she became an internet user at the age of 100.

Lanckorońska’s donation of priceless works of art will go down as one of the most significant events in the history of Polish culture after 1989. She donated, inter alia, paintings by Rembrandt to the Royal Castle in Warsaw. In turn, the Wawel Royal Castle was endowed with Italian works from the 14th to the 17th centuries.

She died in Rome on 25 August 2002, a few days after her 104th birthday. In her obituary, the Lanckoroński Foundation asked that donations be made to the John Paul II Foundation in lieu of flowers. The money was to be used for the education of young people from Central and Eastern Europe, especially from the former Soviet Union.

She is buried at the Campo Verano cemetery in Rome.

In what was most likely the final interview she gave, when asked by Jacek Moskwa what she would like to give to the Poles when donating works of art, Lanckorońska replied: ‘I would like to give them everything that is supreme in its genre. Masterpieces are the greatest school of a nation. If, for example, Malczewski creates art, it raises the nation’s general level significantly. I’m talking about Jacek Malczewski because I knew him well, and I found his drawings in a broken chest of drawers, destined to be burnt.’

In working on the article, I used, inter alia: Karolina Lanckorońska, Wspomnienia wojenne (Kraków 2011); Teresa Chynczewska-Hennel, ‘Karolina Lanckorońska (1898–2002). W stu dwudziestą rocznicę urodzin’ (Studia Kobiece. Scientific Journal of the Institute of Women’s Studies, Y: 2018, fascicle 2); Elżbieta Orman, ‘”Energiczna pedagogika” Karoliny Lanckorońskiej. Organizacja studiów dla żołnierzy 2. Korpusu we Włoszech w latach 1945-1947’ [Organisation of Studies for Soldiers of the 2nd Corps in Italy in 1945–1947] (Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. Prace Historyczne, Y: 2006, fascicle 133); as well as Karolina Lanckorońska’s Legacy from the Research Archives of the Polish Academy of Sciences, and the Polish Academy of Learning in Krakow.

Author: Marcin Wilk – writer and journalist. Author of two biographical books and the historical reportage Pokój z widokiem. Lato 1939 [A room with a view. The summer of 1939]. He is currently working on his PhD in the field of interwar social history, and on a biographical book about Karolina Lanckorońska.

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki