A single day in June 1976 showed how fragile the public’s confidence in Gierek’s team was after almost six years in power.

by Paweł Sasanka

The fourteen-year rule of Władysław Gomułka ended in the socio-political crises of March 1968 and December 1970. After the December tragedy, in which the army and police opened fire on workers, Edward Gierek took the helm of the government in the party and country, just eight years younger than his predecessor yet, in terms of mentality, a generation younger than Gomułka.

Following the intervention of Warsaw Pact troops in Czechoslovakia, which suppressed the Prague Spring experiment, deeper reforms were in sight. The new team was less ideological and more pragmatic than its predecessors and, like them in 1956, needed public trust. As part of the ‘new opening’, it made a number of goodwill gestures towards people of culture, the Church, and repressed opposition circles. It emphasised its liberalism, ‘technocratism’, and a new style of exercising power, admittedly mainly in the propaganda dimension. At the same time, it focused attention on improving living conditions in society, and attempting to modernise the economy. Gierek’s team decided to make an investment leap comparable in scale to Stalin’s Six-Year Plan. It was to be financed by foreign loans. This programme and the promise it contained were excellently expressed by the slogan accompanying the Sixth Congress of the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR) in December 1971: May Poland grow in strength and people live more prosperously.

Gierek-era dolce vita?

The first years of the decade were a period of relative prosperity, likely the most socially peaceful period in the history of the Polish People’s Republic, labelled by historians the belle époque of real socialism, or – more familiarly – ‘bigos[1] socialism’, in reference to the policy of bribing society practised in Hungary by János Kádár, and referred to over there as ‘goulash socialism’. The most important ingredient of this ‘bigos’ was the year-on-year improvement in the material living conditions of Poles made possible by, among other things, the inclusion of new groups of the population in the social security system and, in particular, rising salaries and food prices maintained at the same level. The latter would not have occurred to such an extent had Gierek’s team not ‘frozen’ food prices at the outset, and later been forced to withdraw from the Gomułka-era food price rise, the direct cause of the December 1970 strikes. There was no other way to quell the mass strike of female textile industry workers in Łódź that broke out in November 1971, calm the public mood, and ultimately leave the December crisis behind.

The foundation and the detonator

Communicating the withdrawal of the price hike in February 1971, the new Prime Minister, Piotr Jaroszewicz, spoke of removing the ‘direct cause of working class discontent’. This forced concession formed the cornerstone of the construction of Gierek’s ‘second Poland’, as well as a detonator embedded in it: an element of the social contract that allowed the regime to rule peacefully as long as it satisfied the economic aspirations of society. The price of food – especially of meat – which had for years been a burning issue in the Polish version of socialism, eventually became a political problem of utmost importance. On the part of the authorities, irrespective of official optimism and assurances that unchanged food prices are a ‘permanent achievement of the post-December policy’, it was soon realised that Gierek’s team was hostage to the situation. The approaching (and repeatedly postponed) date of ‘unfreezing prices’ triggered successive waves of speculation and rumours across the country, with people besieging shops. This brought the problem to the attention of those in power, and in fact proved the conditionality of the trust that society had placed in Gierek’s team.

After several years of relatively good supply, from 1973 onwards, shops began to periodically run out of meat again, and the deepening market imbalance heralded the build-up of economic tensions and the crisis that developed in the second half of the 1970s. Not knowing any other way of restoring market equilibrium than a one-off ‘price operation’ modelled on the drastic price hike of 1953 (directly from the arsenal of Stalin’s economic policy), the authorities did much to delay it this time, for as long as possible. This was successful until mid-1976. In economic terms, the increase had already been justified since 1973; in 1976, the symptoms of economic sluggishness, and the exhaustion of the potential of the ‘dynamic development’ policy were already clear.

The ‘Price Operation’

The crisis related to the attempt at introducing a rise in food prices in June 1976 is distinguished by the fact that this time Gierek’s people, mindful of the circumstances of the fall of their predecessors, made efforts not to repeat their mistakes. They chose a convenient time for the ‘price operation’, just as summer holidays were about to start, and shifted the burden of personal responsibility from Gierek and the party to the government (and Jaroszewicz personally); the operation was also legitimised by the Sejm. They announced that the increase had been preceded by consultations at the largest industrial plants, and that it would be compensated for. The mobilised security apparatus tried to monitor the situation in industrial works, to limit the risk of strikes, their scope and, above all, to avoid fatalities. Of key importance was the decision imposed by the authorities (not without resistance from the Ministry of the Interior) that, in the event of intervention on the streets, compact militia units should not be equipped with firearms and live ammunition. Unlike any other previous government, Gierek’s team controlled the course and scale of the June crisis to some extent.

It is quite a paradox that, despite its considerable baggage of experience from December, they prepared the price increase in a form that provoked another mass revolt of society. The population expected this, and – as suggested by the results of sociological studies (symptomatically conducted after rather before the event) – would be willing to accept it on the condition that the scale of the increase was smaller, and that the price rise was introduced progressively. Meanwhile, the draft legislation announced by Jaroszewicz in the Sejm on 24 June took society by surprise for a number of reasons.

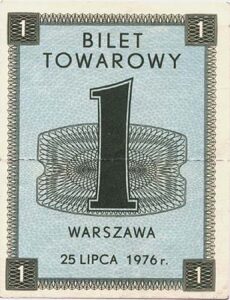

Firstly, owing to the draconian scale of the increase, and the number of items growing in cost. Let us recall that the prices of meat and fish were to increase by 69%, dairy products by 64%, rice by 150%, and sugar by 90%. Secondly, due to the unjust nature of the compensation announced by Jaroszewicz, people earning less than PLN 1,300 were to receive PLN 240, while those earning more than PLN 6,000 were to receive up to PLN 600, i.e. more than twice as much, which was interpreted as favouring the best-off ‘people in power’. Thirdly, poorly concealed arrogance was also a factor. Jaroszewicz presented the increase as a ‘draft’ submitted to the Sejm for approval, even though there was no doubt that the decision had been made, the price lists had been printed, and the promised ‘social consultation’ was a mere smokescreen. All this determined the outbreak of the revolt.

Had the price hike been implemented, food prices would have risen by an average of around 40 per cent virtually overnight, including, as mentioned, those of processed meat and fish by an average of 69 per cent, and of better types of meat and cold cuts by as much as 110 per cent. For example, a kilo of boiled ham would have risen from 90 to 186 zlotys (107 per cent), and Edam cheese from 48 to 80 zlotys (67 per cent). This meant a sharp deterioration in the living standards of the worst-off sectors of society, especially workers. The authorities were unable to satisfy the awakened material aspirations of society, which is a historically proven recipe for provoking revolts and revolutions. It looked like the authorities were making an attack on the standard of living reached so far – and thus breaking the agreement made with society in 1971. Moreover, several years after Gierek’s people had ascended to power, the post-December ‘renewal’ of the power exercising style was now nothing more than merely an empty slogan. Enough fuel had accumulated for another crisis – the pay rise was only a fuse.

While the outbreak of social protests on 25 June 1976 was not a special surprise, what was surprising was their geographical dimension. The authorities were counting on strikes in large industrial centres, including the Baltic Coast. However, these calculations were confirmed only to a small extent: approx. 80,000 people participated in the strikes at 97 to 112 plants in 24 voivodeships (provinces), while many others expressed their indignation during official ‘consultations’ and talks at their workplaces. The highest number of strikes was recorded in Mazovia. Street demonstrations and clashes with the militia took place in smaller centres: in Radom, where, for example, the building of the PZPR Central Committee was demolished and set on fire, and street clashes were also violent in Ursus and Płock. As a rule, it is possible to indicate, after the fact, why the protests had taken place in these and not other places, where people had more reasons to revolt. It must be admitted, however that, apart from inflammatory factors, chance had played a large and sometimes decisive role. Was that what had happened in Ursus and Płock?

Radom

Describing the protest as briefly as possible, let us note that it proceeded according to the scenario resembling the course of the events in Poznań in 1956, and Gdańsk in 1970. It began with a strike at the largest factory in Radom, the Łucznik armaments plant named after General ‘Walter’ – Karol Świerczewski, and was joined by the workforce of 25 factories – approx. 17,000 people in total. The strike evolved into a spontaneous demonstration aimed at the local authorities, and, subsequently – due to the lack of their reaction – escalated into incidents symbolised by setting fire to the building of the party’s provincial committee, destruction of symbols associated with communism and references to national symbols. It is estimated that, at the climax, more than 20,000 people took part in the clashes in the streets. Perhaps the repetition of the scenario known from other ‘Polish months’ was particularly probable precisely in a smaller industrial centre, such as Radom, where working and living conditions were clearly different from those in larger cities, and where workers knew, on the one hand, that mass strikes and protests had already forced the authorities to retreat once in 1970/1971, and, on the other, they had not personally experienced the trauma of the deaths lived by workers on the Baltic Coast.

The issue of the responsibility of the authorities for the escalation of the conflict should not be underestimated. The demonstrators persuaded the First Secretary of the Central Committee to send the demand to cancel the pay rise to Warsaw and patiently awaited an answer. Only after two hours, when they realised that the answer would not come, and that there were no more party representatives in the building (they had been evacuated by Security Service [SB] officers), did they start destroying equipment and, before 3 pm, set the building on fire. Secondly, it should be noted that the decision of sending Motorised Reserves of the Citizens’ Militia (ZOMO) troops from Warsaw, Łódź, Kielce and Lublin to Radom, as well as students of the Higher School for Officers of the Citizens’ Militia (MO) in Szczytno – approx. 1,550 officers altogether – was made before noon. It was not until the entry of compact MO units into the city that the phase of violent street clashes began. It was then that two demonstrators – Jan Łabęcki and Tadeusz Ząbecki – died in a tragic accident, killed by a speeding trailer filled with concrete slabs, which they had been pushing towards approaching ZOMO officers. Apart from the building of the Central Committee of the PZPR, those of the MO and the Voivodeship Office were also attacked. Shops were devastated and looted. It was not until late in the evening that the situation in the city was brought under control by militia units.

Ursus and Płock

Almost the entire workforce of the Ursus Mechanical Works was on strike from early morning. Following unsuccessful talks with the management, which boiled down to appeals to return to work, the workers went to the nearby railway tracks connecting Warsaw with Łódź, Poznań, and Katowice, in order to block traffic, and inform other people in Poland about the strike. In order to permanently block the tracks, they attempted to cut the rails with an acetylene torch in the afternoon and, when this failed, unscrewed them and pushed a locomotive into the resulting gap. The police intervened at around 9:30 pm, after Jaroszewicz’s evening TV speech, in which the Prime Minister cancelled the contentious price increase. The crowd then dwindled to a few hundred people. After a short clash, a manhunt for the demonstrators began.

The course of events in Płock was determined by the situation at the Mazovian Refinery and Petrochemical Plant (today’s petrochemical concern Orlen S.A.), where the strike started in the morning in several departments, and among the employees of enterprises working on the premises of the plant. After the end of the first shift, around 2 pm, some participants marched in a spontaneous rally at the main gate towards the building of the party’s provincial committee. As they approached the city centre, the march grew and, at around 5 pm, there were two to three thousand people in front of the party’s headquarters. The First Secretary of the Voivodeship Committee, Franciszek Tekliński, addressed the crowd. Some demonstrators also headed for other factories, but their workers did not join the protest. Following the announcement of cancelling the pay rise, the Voivodeship Committee building was pelted with stones, several windows were broken, and the fire brigade’s patrol car was attacked. Around 9 pm, demonstrators were attacked by ZOMO units brought from Łódź.

The wave of strikes on 25 June 1976 was comparable to the strikes that had taken place in December 1970 and January–February 1971, and were not limited to one region of the country, threatening to spread rapidly. Fearing the repetition of the December 1970 scenario, the authorities decided to suspend the price increase on the evening of 25 June: the decision was announced in an evening TV address by Prime Minister Piotr Jaroszewicz, who signed it in front of the public. For the strikers, this was a great success. In just one day – an unprecedented scenario – society had forced the authorities to back down. In the following days, however, many of the workers on strike that day were to pay a high price for it.

Retaliation

The revenge of the authorities was experienced especially by the demonstrators in Radom and Ursus. The detainees were taken to the MO headquarters and detention centres, and brutally beaten while being led through rows of militiamen, derisively referred to as ‘fitness trails’. The victims of these brutal beatings were also random people, such as Jan Brożyna, likely fatally beaten by an MO patrol. Another fatal victim of the June repressions was Father Roman Kotlarz from the Pelagów parish near Radom, who on 25 June had accidentally found himself among the demonstrators, and later prayed publicly for the workers during a holy mass. This brought him to the attention of the authorities, and he was summoned for questioning to the prosecutor’s office, harassed, and beaten by SB officers. He died in August 1976.

A total of 353 motions for the punishment of detainees were submitted to misdemeanour courts, including 214 in Radom, 131 in Warsaw, and eight in Płock. A total of 314 custodial sentences were handed down, including 250 for three months each and 50 for two months each. In Radom, 51 people were brought to trial under the accelerated procedure. A total of 42 people were sentenced to prison terms, 28 of which for five months to a year, while 14 were sentenced to two to three months’ imprisonment. In Radom, 188 people were tried under the regular procedure. In July and August 1976, several show trials were held, in which the defendants were tried on the principle of collective responsibility, and the composition of the jury was such that the June events were presented as the work of criminals and hooligans. In the show trials, eight people were sentenced to draconian terms of eight to ten years in prison, eleven were sentenced to terms of five to six years each, and the others to terms of between two and four years’ imprisonment. In the Ursus trial, seven people were sentenced to prison terms ranging from three to five years. In Płock, 34 people were tried, 18 of which were sentenced to prison terms from two to five years, 15 – to suspended sentences, and one was acquitted. In total, 272 people were tried for participation in the protest of 25 June 1976. The sentences and judgments ordered by the political authorities after the suppression of the June protest made a mockery of the rule of law, even in the light of the legislation in force at the time.

The retreat

The failure of the ‘price operation’ undermined the authority of Gierek’s team, especially the position of Prime Minister Jaroszewicz, who had been an advocate of the price increase before society. On 26 June 1976, during a teleconference with the First Secretaries of the party’s Voivodship Committees, Gierek ordered the calling of rallies of thousands of people, and the launch of a propaganda campaign. It was intended to conceal the defeat, but also to stifle social resistance and prepare the ground for another attempt at introducing a price rise, which ultimately did not happen, due to the strong intervention of the Kremlin (during a conference of leaders of European communist parties held in Berlin on 29–30 June 1976), worried about the destabilisation of the situation in Poland, and very cautious about the ideas of Gierek’s government. In the circumstances, the authorities were left with the choice of withdrawing from a one-off price increase, rescuing the market balance by half-measures, and focusing on the increasingly deregulated and crisis-ridden economy.

A propaganda campaign of hatred swept through Poland for several days, in the press, radio and television, and in the form of rallies of several thousand people in the main squares and stadiums of cities and towns, often in a surreal atmosphere. Its culmination was a hate rally held at the Radomiak sports club stadium in Radom – a city that was to be shamed. A thread that constitutes part of another story already is the operation helping the repressed for their participation in the June 1976 protest, which spontaneously began in July. People from different – even very distant – ideological backgrounds provided assistance, which resulted in the creation of the Workers’ Defence Committee in September 1976, the development of an organised opposition, and the nucleus of a civil society.

Author: Paweł Sasanka – PhD in History, employee of the History Research Office of Institute of National Remembrance

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki

[1] A typically Polish dish made of sauerkraut and meat, served hot.