While writing biographies of great writers, we, often unconsciously, look for something unique, or characteristic about the individual path they pursued in their lives. This is probably due to a legacy of romanticism that we are not aware of. Thus we are facing some troubles looking at Jan Kochanowski in a different way.

by Wojciech Stanisławski

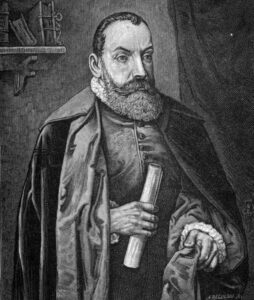

His biography is absolutely typical of the second half of the 16th century, a period usually considered the “golden age” of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. At that time, Kochanowski distinguished himself as a nearly emblematic nobleman, courtier, landowner. The fact that he was so unique manifested itself in his work and made him the greatest poet not only of 16th-century Poland, but also among other poets writing in Slavic languages of the time. His accomplishments as a soldier, member of a palestra and clerk allow us to study his life as a “typical representative of his generation and class”.

When was he born? In 1530, probably, although in the first quarter of his biography dates are accompanied by quite a few question marks. His parents were moderately prosperous nobles from areas located in the heart of Poland on the border between the Sandomierz and Mazowsze regions. His father, Piotr, in addition to owning land and property, held numerous offices, and was, among other things, a border official and regional judge. Such a background created a firm foundation for Kochanowski, and for most of his life he was concerned about the fate of his family estate. First, he took care of the inherited estate after the death of his father, and later saw to its fair division between himself and his brothers. At the end of his life he managed to expand it by buying the villages adjacent to his property. He was very persistent and when suing others at local courts he was not litigious, but determined enough to get his way – and thus we are able to see how a 16th-century nobleman was obligated to the expectations of neighborly connections, legal regulations and family compromises.

Piotr Kochanowski was rich enough to educate seven sons, including Jan, whose history can serve as a good example of the 16th century education system. He began his education at the manor in Sycyna under the watchful eye of a teacher whom we know only by his Latinized name Jan Silvius. Later Kochanowski continued in the school run by the Benedictines in nearby Sieciechów. As a teenager in 1544, he entered the Artium Faculty at the Krakow Academy. It is presumed that he left it after five years in order to study at one of the German universities in the spirit of the Reformation at that time, likely to Leipzig or Wittenberg. He certainly got to the Lutheran Königsberg (1551-1552), but from there he headed in the opposite direction, the most popular route iofn education among Polish nobility of the Renaissance – Italy! More specifically, Padua.

He would return to Padua twice, interrupting his studies for several months to settle business or inheritance matters in Poland. He certainly studied there in 1552-1555. We also know about his next several-month stays, the first in 1556 and the next two years later. The third visit ended with a Renaissance Grand Tour including a journey to Florence and Bologna and probably also to Rome and Paris.

There are not so many direct testimonies from these journeys. Only entries in the books, payment certificates, a handful of dedications and letters, and faint echoes of his election as a Polish “consultant” (formally a doctor, but at that time it was already an honorable dignity, testifying only to the trust of fellow countrymen) in Padua. The testimony to which we will return in a moment is a rich source of references and experiences in Kochanowski’s work. Songs and Laments were written by a Renaissance man whose knowledge of the tensions and discoveries of contemporary culture was not second-hand (as was the case of education in provincial institutions) nor superficial and based on a several-week mission or journey. On the contrary, he was immersed in the civilization of his times.

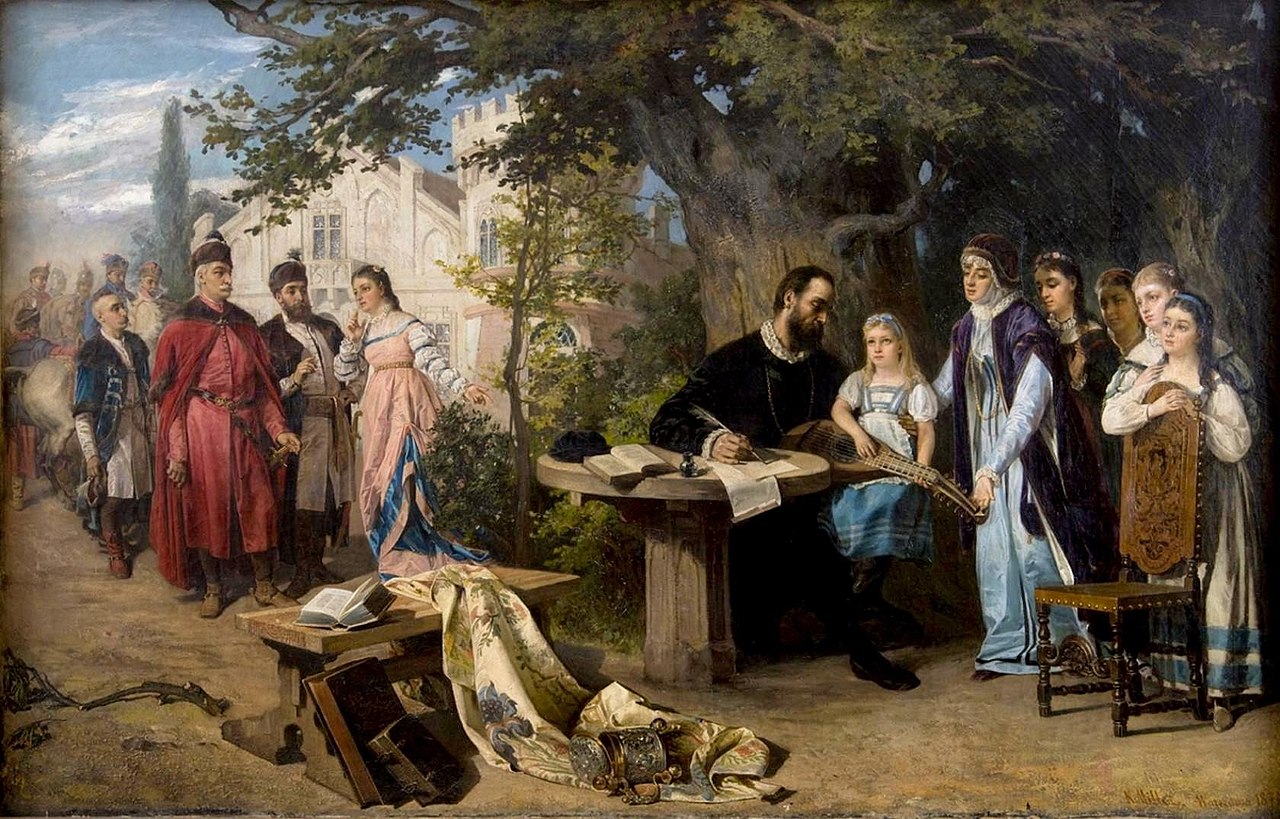

He was equally deeply immersed in court and political life for years. Here we have plenty of testimonies. As in the case of the Kochanowski’s education or property matters, on the basis of his life one could write about the career paths of an educated 16th century nobleman, and about the cursus honorum in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Influential courts – bishops, province governors, senators – needed courtiers, it is almost tautology. At the court of Krakow governor Jan Tarnowski, of the Firlej and Radziwiłł family, or perhaps the bishop Filip Padniewski – at some point one can easily meet a learned man, one with an expertise in Italian and Latin, Jan Kochanowski. There, even before they were published in print, his epigrams, songs and love poems were copied and circulated.

From these courts – he wandered to the court of Chancellor Piotr Myszkowski in mid-1563 and from there to the court of King Sigismund II Augustus. He took part in hunting, war campaigns, inaugurations and bridge openings, but above all – in meetings of the Sejm. Including those with the aim to elect the king – he participated in negotiations around the candidacy of the first elected ruler. Kochanowski was present during the ceremonial coronation of Henry of Valois in February 1574, and half a year later, after the king’s abandonment of the royal throne, Kochanowski took part in a kind of international poetic duel, as we would say today, half a millennium later – in a “slam”. In response to the malicious epigram “Adieu a la Pologne” (“Farewell to Poland” written in a rather peevish tone) by a member of the king’s retinue Philippe Desportes’s, Kochanowski wrote the equally spiteful “Gallo crocitanti”, meaning “Rooster crowing too loud”.

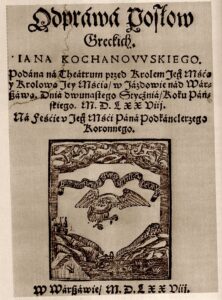

However, Kochanowski’s works that referred to being a citizen were not only spiteful and light in tone. One could compile a catalog of the most important issues of foreign and domestic policy of the mid-16th-century Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from the topics that appear in his Songs or his native ancient tragedy, such as Odprawa posłów greckich (The Dismissal of the Grecian Envoys), written in the spirit of Iliad. The threat from the Tatar (Song of the Desolation of Podolia) and from Moscow, French and Austrian candidacy for the Polish throne, the “feebleness” of a nobility who evaded both taxes and wars – these are problems taken from Cicero. In Songs devoted to the beauty of life, the order of the sublunary world, and the sorrows of evanescence, we can hear the echoes of Horace.

There were more and more Horatian themes in Kochanowski’s poetry as he settled down and devoted himself to his estate and country life. He was still being invited and listened to at the court of the second praiseworthy king, Stefan Batory. Kochanowski would retain the dignity of the royal secretary until the end of his life, but it would be purely nominal. In 1575, Kochanowski bought the village of Chechły near Czarnolas, most probably at the same time he married Dorota Podlodowska. This does not mean that he abandoned public life. It is said that he died hosting a meeting of Polish senators in Lublin in August 1584 while seeking clarification of the circumstances of the death of his brother-in-law in a mission to the Ottoman Porte. In the last decade of his life there were some issues that seem too modest to overload his biography, but are still very present: the return of 4,000 zlotys in loans, the purchase of horses and two fields of arable land, lease of a village and a mill. Like the ancients Athenians, mythologized for centuries, elevated to the dignity of warriors, philosophers and athletes, before subsequent generations of researchers showed them as precarious breeders of pigs, vines and onions – Jan Kochanowski appears to us, after tilting the olive wreath a little to the side, as a landowner concerned whether his hops would grow well that year, or if the geese would lay eggs and the harvest be good.

It is no dishonor to him. Having read plenty of bucolic poetry, for which he even created in Polish the synonym of “skotopaska” (that is “the song of the shepherds”), this was the kind of life he wished for himself: at court, accepting invitations, and traveling, but above all – the life of a land owner. His image, which he sketched himself in Songs and Trifles, is idealized a bit. A landlord sitting with a full pitcher, among friends and family, in the shadow of the linden constantly referred to in his poems remains emblematic for Polish literature as a picture not only of order and 16th-century Poland’s prosperity but it is also an image of a fulfilled man. A man free from dilemmas, alienation or analyzing how his life could be different. Perhaps that is why he seems to be a model renaissance poet to us?

Not only because of that. The long list of his readings and achievements is more important. After reading Martial, the Vulgate and Greek translations of the Bible, Theocritus, Petrarch, Ronsard – he easily reached for their diction and their concepts, expressing them in Polish without difficulty, without artificiality, and without archaisms or Latinisms. Having developed a flexible language which allowed him to write about all aspects of life, low and high, private and public – he described the golden age of the Republic of Poland incidentally, utilizing at the same time all the poetic tools and techniques that he learnt at the university and in libraries. “The privilege of the beginnings, when every sentence of a virgin language shines” – according to Jan Błoński, a great historian of literature who wrote about this phenomenone.

Kochanowski was not content to write “catalogs” like many poets-chroniclers, or poets who wrote about what they saw. He was perfecting the form, writing Horatian carmina in rhymes, creating dozens of new words that often had their root in Polish, such as “koziorożec” (“capricorn”), “noworodek” (“newborn”) or “skrzypce” (“violin”), and sometimes are associated only with his work, like the unforgettable „białoskrzydła” (“white-winged”) (i.e. the boat under full sail in the prologue of The Dismissal of the Grecian Envoys). Dividing his work in couplets, and looking for tasty details, we find in it descriptions of drunkenness and chess matches, haymaking and the rites of Saint John, going on missions and cavalry charges, courtship and mourning.

Usually, we are far from the poets who lived five and a half centuries ago. They are honored, monuments are erected to them and commemorative plaques are placed on walls, their names can be found in all textbooks, school and academic, sometimes they are sincerely adored and recognized also by people who are not familiar with literature on a daily basis, however, they are only exceptionally read by a wider group than a circle of experts and philology scholars. The Dismissal of the Grecian Envoys is rarely being staged, and if so – it is in school theaters. “EPITHALAMIUM For the Wedding of His Excellency Lord M. Krysztof Radziwił, Prince in Birże and from Dubinek, Hetman and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (…) and Her Majesty Duchess Katarzyna Ostrowska, Governor of Kiev etc…” is actually read and cited only by specialists. But the joke of the epigram “On Doctor Spaniard” can be heard to this day in cabaret. The praising of the world in the opening of the collection of Songs (“What do You want from us, Lord, for Your lavish gifts? / What for the benefactions, which have no limits? / The Church will not contain You, You are everywhere: /On the earth, in the depths, the sea, the open air.” Tr. Michael J. Mikoś) – one can still hear sung by the faithful at mass in every second parish church in Poland; all the better because it sounds so much more beautiful than many “sacral nursery rhymes”. And finally Laments: a series of poems mourning Kochanowski’s daughter, who died at the age of two and a half years, in poems stripped of all rhetoric and Italian language: a devastated father who is not comforted by the vision of Orszulka either in Paradise or in Elysium.

This is quite significant enough for a poet to remain in readers’ awareness after five and a half centuries.

Author: Wojciech Stanisławski

Transation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin