Many film roles, dozens of opera roles, Jan Kiepura, the “second Caruso”, conquered the world with his golden voice and charisma. How did this Polish boxer become an internationally famous singer?

by Magdalena Mikrut-Majeranek

From sports to concert halls

The road from sports to art was a bumpy one. Jan Kiepura was a man of many talents. However, he was not able to define the shape of his professional career right away, which is why he took up various roles. As a child, he joined the scouts, which he exchanged later for a boxing club. He sang in the school choir and played in the football team of Victoria Sosnowiec. However, he is now remembered as an opera singer.

The “king of tenors” Jan Kiepura was born on 16 May 1902 in Sosnowiec to a wealthy family of bakers and real estate owners. His younger brother by two years, Władysław, was also famous for his beautiful voice. He grew up to sung at the Krakow Opera, the Grand Theater in Warsaw, and on stages in Berlin, Budapest and Dresden. In 1938, he accepted an offer from La Scala in Milan, where he performed until the outbreak of the Second World War. However, his post-war fate would be different from that of his more famous brother.

During his school years, Jan Kiepura was distinguished by his cheerful character. It was said that his good humor was infectious. However, he did not excel at school – he studied well but not regularly. Even as a teenager, he did not show any interest in music. He was even known for avoiding singing lessons! The situation changed dramatically after a family visit to relatives in Krakow, where they spent Christmas. There Jan met a singing teacher who quickly noticed the enormous potential hidden in the young man’s voice. His parents disregarded the educator’s remarks about their son’s “golden throat” because they had a different future for him: Jan was to become a lawyer. But the teacher did not give up and had a conversation with Jan.

The boy took this conversation to heart. After returning home, he gave up sports and took up singing. However, he had to postpone his dreams – after years of partitions, Poland had returned to the map of Europe and needed to fight for its borders. As Jerzy Waldorff wrote, during the Silesian Uprisings (1919-1921), Franciszek Kiepura’s bakery was transformed into an ammunition and weapons warehouse, and Jan was involved in assembling machine guns. In 1919, as a volunteer, he enlisted in the 1st Bytom Rifle Regiment and took part in the 1st Silesian Uprising. He emerged unscathed. As Wacław Sobol, one of his colleagues recalled, Kiepura even gave concerts in the army: he would simply stand on a barrel and delight his comrades with his voice. This does not mean, however, that he survived the uprising far from the front – on the contrary, he often showed courage in the field, e.g. saving the lives of colleagues.

When the fighting stopped, Kiepura returned to school, where he passed his final secondary school exams, and then, following the wishes of his parents, he began studying law – first in Krakow, and then at the University of Warsaw. He thought about quitting his studies and devoting himself to music, but his father threatened stop supporting him. The ambitious boy decided to combine both and, while continuing his studies, he took singing lessons from eminent Warsaw professors. Franciszek Kiepura was not satisfied with his son’s decision and ultimately cut him off. However, the young artist did not get discouraged and made his living by giving concerts in provincial towns. This turned out to be another valuable lesson for him.

However, the fees he received were small and were not sufficient to pay for accommodation, travel and meals. Eventually he reached the brink of collapse and considered returning home. The rebellious young man, however, had volunteered beforehand at the Grand Theater in Warsaw. The examiners noticed his talent and admitted him to the opera. He was entrusted with the role of the leader of the highlanders in Act III of Halka. Initially, he sang in the choir – probably because the full-time tenors, jealous of their younger colleague, feared for their positions, and therefore hindered his promotion.

Yet, he did not have to wait too long for his debut as a soloist. On 11 February 1925, he appeared in the well-known operas “Faust”, “Rigoletto”, “Cavalleria rusticana” and”Halka”. A few months later, he took part in a singing competition organized at the Warsaw Hippodrome. It was then that the 23-year-old singer was awarded the title of “King of Polish Tenors.” After this success, everything went very quickly.

The Parisian impresario Kahn, who was present at the competition, made Kiepura a lucrative offer – a tour of France. The young tenor was given a train ticket and money. When he informed the opera management about it, the opera, wanting to keep the singer at home, offered him a new contract. He did not agree and left for France. But he did not reach his destination, and instead stayed in Vienna where he lived for a year.

Master of self-presentation

In the Austrian capital, Kiepura joined Guttmann’s concert bureau. He was confident and convinced of his talent. Slowly, and methodically, he was working on becoming a rising star. One day he showed up at the Viennese telephone exchange. The choice was not accidental – it was there that every evening foreign correspondents from many countries gathered and called their editorial offices to report on events. Kiepura told the dismayed journalists that he would like to be interviewed about his career plans. Then he sang the aria “Vesti la giubba” from Ruggero Leoncavallo’s opera. The hall with telephones turned into a concert hall. After a few days, newspapers in many countries wrote about “The New Caruso from Poland”. After this, Kiepura himself, as well as Michał Orlicz, who promoted him, sent journalists news about the singer. Kiepura turned out to be not only an outstanding soloist, but also a master of self-presentation and self-promotion.

He was enthusiastically received wherever he went. “Things happened like an avalanche. Every day – thanks to perfectly organized press propaganda, Kiepura became more popular. Every day they brought new sensational details about the “Polish Caruso”, wrote Roman Haber in his biography of the singer. Soon, the director of the Viennese Staatsoper, Prof. Franz Szalk offered Kiepura a role in “Tosca”, where he was to be a partner of the Czech singer Maria Jeritzie (1887–1982). She supposedly liked him so much that she also performed with him in Paris in May 1928. Eventually, however, her enthusiasm waned. She took offense when the audience applauded Kiepura more than her.

The opera company was dissatisfied with employing Kiepura. There was also a dispute, known as the war of two tenors, between Kiepura and Leo Slezak (1873–1946), a recognized tenor and considered the greatest singer of the State Opera in Vienna. Both aspired to the main role in the opera “Turandot”. In the end, the director decided to organize 2 premieres – in one the main role was entrusted to Slezak, and in the other – Kiepura. Although Slezak, dissatisfied with the developments, initially sabotaged this solution, both premieres took place.

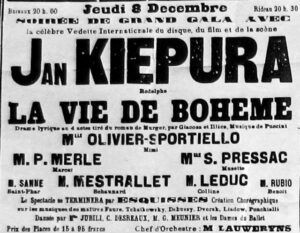

“Kiepura sings mostly in Polish. He captivates, and enchants listeners. The program is over – and no one leaves the room. The hall howls, rumbles, like a hurricane. (…) A new Polish star! (…) Jan Kiepura conquered Vienna. Now he is going to London, Paris, America”, wrote Roman Hernicz on 23 October 1926 in “Katolik Codzienny”. In the same year, the artist went on a tour of Western Europe. A month later “Dziennik Berliński” reported that “For years no singer has collected such tributes in Berlin, for years, no tenor has electrified the audience of the city of Spree with such artistry, as the 24-year-old Polish tenor Jan Kiepura did in the last days”. From Berlin he went to Vienna, then to Swiss Bern, Prague and finally to La Scala in Milan. He sang at London’s Covent Garden, Paris’s Opera Comic, Venetian Fenice, and Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires. The whole world wanted to listen to Kiepura.

Viennese society also talked about the Polish singer. “The Viennese press is full of articles about him, ‘N. W. Journal’ and ‘Tageblatt’ publish extensive interviews, in which they even report how Kiepura is sitting, how he smiles, what his tie is, etc.”. And yet chimerical Austrian journalists were reluctant to report on his foreign successes and found a new star – Alfred Piccaver (1884–1958), the greatest rival of the artist from Sosnowiec. Kiepura was receding into the shadows. He decided that Vienna was just a stop on the way to a global career. He decided to go on a tour of European capitals. He also successfully toured South America. He acted in films, making him known to wide audiences around the world for his dazzling smile and singing.

On the big screen and in showrooms

His first appearance on the silver screen took place during the breakthrough to [talking movies]. Kiepura made his debut in the Polish film “O czem się nie myśli” from 1926. Later there was a musical comedy “Die Singende Stadt” from 1930, in which he was accompanied by Brigitte Helm – a German actress-vamp , a star of “Metropolis”. Then there was “Tell Me Tonight”, “Ein Lied für Dich” and “Mein Herz Ruft Nach Dir”. Some of them were recorded in three language versions: German, English and French. In the last of the mentioned films, Kiepura appeared together with Mártha Eggerth (1912–2013). In 1936, they stood on a wedding carpet. This Hungarian operetta singer had developed her career thanks to her fellow countryman Imre Kálmán, the famous composer and author of the operettas “The Princess of Cardia” and “Countess Marici”, both popular in Europe.

Jan Kiepura didn’t only visit European salons, concert halls and operas. In July 1936, he received an invitation from President Ignacy Mościcki, who received the singer at a castle in Wisła. In 1937, he sang opera arias at the World Exhibition in Paris, and in 1939, he performed for miners and workers of the Karwiński Basin. The performance took place in the square in front of the Barbara shaft, and over 10,000 people listened. He sang wherever he was invited. He also became an ambassador of Polish culture thanks to radio broadcasts, recorded albums and films, which made him an international idol.

A singer with a big heart

The tenor from Sosnowiec, like all stars, had his whims. He hated the smell of cigarettes, and he hated someone smoking in his company. He always had an arsenal of gargling agents with him. Years later, his biographer noted that the master had incurable, and chronic rhinitis. Kiepura was afraid of catching a cold that would affect his condition, and his work. As reported in “Express Zagłębie”: “If Kiepura sees that you are wiping your nose (…) – he will not want to approach you. If you cough, he will ask you to be removed.”

Jan Kiepura did not forget about his former friends. He helped, among others, Mieczysław Szafruga in getting to New York, where his childhood friend became a valued ship builder at the Rockefeller shipyard. He was also happy to do charity work. He sang in 1934 in Krynica for the victims of the flood. Two years later, the income from his concert supported the construction of the National Museum in Krakow, and in 1937, as part of the “Winter Help” campaign, he gave concerts at the Warsaw Philharmonic for the poor and unemployed.

In 1938, he and his wife moved to the south of France, but due to the rise in anti-Semitism (his mother was of Jewish origin), they were forced to leave Europe and permanently move to the United States. There Eggerth signed a contract with the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer label, and alongside her husband she successfully performed on Broadway stages, including in The Merry Widow by Franz Lehár.

When the Second World War broke out, Kiepura returned to France, where the Polish army was being formed. He wanted to support his compatriots with his voice. He did not stop touring, and the income was donated to support the fighting for Poland. He also used the opportunity to remind the public in the West of the tragic fate of Poles under the occupation.

After the war, he stayed abroad. The Communist authorities did not even allow him to attend the funeral of his father, who died in February 1951. The tenor did not return to his homeland until 1958. His arrival was accompanied by enormous enthusiasm of the audience, for which he gave many concerts.

The giant’s last farewell

The Polish singer was an artistic phenomenon. “You can just risk saying Kiepura has some magic power that changes people. This calm and difficult usually (…) Krakow suddenly turns into some southern “singing city”, reported “Nowiny Codzienne” in 1937, after a performance at the Stary Theater. He was known to be direct and humorous. He had great control over the crowds. “Kiepura has one of the biggest secrets, which is the ability to connect with the audience. He understands his listeners excellently – he feels that they are close to him, and he does not consider the stage as a pedestal separated from the audience,” assessed the editor of “Nowiny Codzienne.” Kiepura was a hard-worker but the intensity which he brought to his concerts was often criticized. It was emphasized that despite his enormous success, he remained “a simple boy from Sosnowiec with a warm heart”. Roman Hernicz, writing a novel about Kiepura in the 1930s, entitled it “The Brain and the Larynx”. And it is a good synecdoche for this outstanding artist.

The golden-voiced singer died suddenly. In June 1966, Kiepura had signed a contract with the Metropolitan Opera in New York, and shortly after that began rehearsals for Bizet’s “Carmen”. However, he did not fulfill the contract. On 15 August 1966, the tenor’s life ended with a heart attack. He died at his home in Harrison, [New York], USA. A coffin was placed in the hall of the Teatr Wielki, so that lovers of his music could say goodbye to the artist. According to his last will, the body was to be transported to his homeland. The plane with his mortal remains on board landed in Poland on 3 September. The funeral took place the next day. Holy Mass was celebrated in the church of St. Cross in Warsaw, and later the artist was laid to rest in Powązki Cemetery. Enormous crowds of fans came to say farewell. In the funeral procession alone, there were more than 200,000 people.

Author: Dr. Magdalena Mikrut-Majeranek

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki