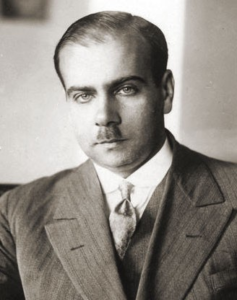

Ignacy Matuszewski was the type of politician who is almost extinct in our country. He was the kind of man who wished to learn something new everyday, assessed each situation in shades of gray and looked for ways to make Poland stronger. His style distinguishes him from other journalists of the interwar and emigration period – says Prof. Sławomir Cenckiewicz, Director of the Bureau of Military History, and editor of the collection of Matuszewski’s writings published by the Institute of National Remembrance.

Michał Szukała: During communism, Ignacy Matuszewski was condemned to oblivion. This is understandable considering his biography and political views. Why, however, has he been remembered again only in recent years?

Professor Sławomir Cenckiewicz: I think that Matuszewski was consigned to oblivion because, among other things, he died only a year after the war ended and was not able to develop his political agenda as he had planned. So he did not become as well-known as many other emigrant activists, such as General Kazimierz Sosnkowski or the presidents and prime ministers of the Polish government in exile. Let us also remember that the Cold War lasted almost half a century. Taking into consideration the scale of hypocrisy and historical manipulation in communist times, it was difficult for people to remember his achievements,. Matuszewski was always mentioned in the Polish People’s Republic in a negative way, the only exception was Andrzej Micewski, an historian who tried to restore his reputation in the sixties. But this was a singular incident. Therefore, it was only in the mid-nineties that the first scholarly articles on Matuszewski began to appear. They were published in niche academic journals. When I discovered him in the mid-nineties, I set myself the goal of restoring him to Polish memory. So I began writing about him.

Which feature of Matuszewski’s personality or work influenced this interest in his biography the most?

It seems to me that I was impressed with his conduct as a Polish person, and I was happily surprised by the kind of patriotism Matuszewski represented. He skillfully combined both romantic and positivistic features. It is an ideal that has always guided me – to be romantic in the fight and maximize goals, but also to be a positivist in the selection of means and in assessing the situation. He was able to be a romantic with a Polish spirit and a positivist in the sphere of everyday professional work. His self-development was a result of his work for Poland. It is a type of politician that has almost become extinct here – someone who wants to learn something every day, assesses each situation in shades of gray and look for ways to make Poland a stronger country.

His friend, the poet Jan Lechoń, said that ‘his dream, never fulfilled, was literature’. How can you define Matuszewski’s journalism style?

Ignacy Matuszewski Sr., was an outstanding expert on literature, mainly on the work of Juliusz Słowacki. His son inherited his style and fascination with literature and poetry. It can be said that when he decided to choose politics, at the expense of literature, Matuszewski retained his literary style, ability to articulate thoughts, and a special type of poetic and literary sensitivity. He was able to combine a literary way of expressing his thoughts with an element of politics. In this sense, his style is different from the one presented by many prominent journalists of the interwar and emigration period. An important feature was also the clarity of his thinking. In the interwar period, his journalism was empirical, and he dealt with economics and statistics in his writing. He utilized statistics and an analysis of economic or military potential, and only later did he share his political reflections with readers. During the Second World War, when he expanded his journalist activity, his style became a little more romantic because he decided that he should inspire Poles to fight.

He combined his beliefs with a clear ideological concept. If we graded important elements of political beliefs for him, then certainly anti-Sovietism should be mentioned first, followed by anti-German feelings, because while he believed that the entire free world was fighting against the Third Reich, he also recognised that the Soviets had followers and advocates around the world. After 1941, when the Soviets became part of the Grand Coalition, Matuszewski became a public prosecutor of Soviet crimes, lies and manipulation, in an attempt to unmask their true aim – to conquer the world in the name of Bolshevism. The result of this attitude was criticism of the Allies, first of Great Britain and then the United States even as they guaranteed to defend Poland’s rights to independence and territorial integrity in the Treaties and the Atlantic Charter. Meanwhile, these countries were pushing us into the hands of the Soviets, treating Poland – and in particular Stanisław Mackiewicz – as a former mistress who should be disposed of in the same manner as unnecessary ballast. The fact that Poland was betrayed by other free countries strongly occupied Matuszewski’s mind.

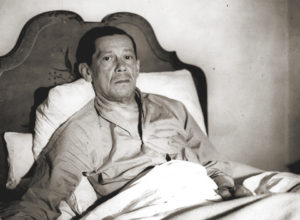

Kazimierz Wierzyński, a poet, gave a speech at Matuszewski’s funeral. He said that Matuszewski ‘was the first of the Poles who predicted that this war, from which Poland was expected to be among the winners, could end in its defeat’. On what basis did Ignacy Matuszewski develop his political calculations and predictions at a time when no one could imagine Tehran or Yalta?

In this context, it is worth mentioning the words of journalist Wacław Zbyszewski, written shortly after the death of Matuszewski, that every politician and journalist should be a pessimist. Just like Matuszewski! Political fortune telling can be rather useful for the national community and the state, because pessimism is a kind of preventive disaster protection. And this is one of the characteristic features of Matuszewski’s thinking, never to be happy with the surrounding reality. His attitude to politics was very empirical, logical and, economic … Statistics and data determined his political thinking. He did not want a situation in which Poland would enter the war first and have to fight against two powerful states at once. He said later that he thought before September 1939 that Poland would be defeated within three months, while it actually was defeated within a few weeks. He even decided that he wasn’t pessimistic enough.

He also emphasized that a state which is sinking into statism must generate corrupt internal relations, because it will arbitrarily determine those who should get rich by creating price fixing, cartels, groups of interest, etc. Hence, he opposed Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski’s reform programme, which meant that Matuszewski, as a liberal, bred many influential enemies – with President Mościcki at the forefront. Probably both sides of this dispute were right, because the world was plunging into statism at the time, but the scale of the internal corruption and the abuse of budget funds in Poland in the 1930s was terrifying.

At the end of August 1939, Matuszewski was very critical of the Sanacja, a Polish political movement that came to power in the wake of the May 1926 Coup d’État. When he was asked by Wacław Lipiński, on the eve of the war, whether he would like to help the government as it faced an upcoming war, he replied that he did not want to have anything to do with those people. As a soldier, he believed that entering the war against Germany and the Soviets at the same time must end in defeat. During the war, knowing that Poland had been abandoned in 1939, he even demanded new guarantees from the West. He believed that if Germany attacked the USSR, the Soviets would join the coalition. Therefore, he could not accept the terms of the agreement with the Soviets of July 1941, because it did not protect Poland against the Soviets in the future.

He could not understand how Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski, who had previously consciously assessed the Soviets, could sign an agreement with Soviet Ambassador Ivan Mayski. It was a turning point, after which Matuszewski actually disobeyed the Polish prime minister who had referred to the ‘word of honour’ given Poland by Churchill and Stalin. Matuszewski knew that such declarations were useless. He knew, and often wrote about the fact that the British and Americans, under the special ‘lend-lease’ act, only supported the Soviets with money and equipment because they wanted Moscow to bear the main burden of fighting and defeating the Third Reich. Poland in this calculation was therefore in a unfavorable position.

Matuszewski monitored the decisions and acts of Sikorski’s cabinet, realizing in 1942 that their policy was favorable to Moscow and that Poland’s politicians were blind to the fate of the Polish officers who went ‘missing’ after 17 September 1939. In February 1942, he published an article in which he dramatically asked Sikorski about the fate of the seven thousand Polish officers who had not reported to any of the recruitment points of the Polish Army in the East. All this intensified Sikorski’s dislike of Matuszewski. Seeking associates in his fight against Matuszewski, Sikorski even got involved with Moscow’s agents in the United States, making the Communist Party of the US his ally.

The roots of the conflict between Matuszewski and the government in exile are already found in the events of Autumn 1939. Even before he begins to criticise the decisions taken by Sikorski, he becomes an ‘unemployed politician and soldier’. Why was there such a rapid reluctance, despite the fact that Matuszewski was a critic of Sanacja, which was in conflict with Sikorski and his milieu?

The reasons for this advancement are not entirely clear. The dislike of Matuszewski was twofold. In September 1939, Matuszewski saved the gold of the Polish bank and submitted a report to Sikorski. According to Sikorski’s diary of activities, he was meeting Matuszewski quite often then. Few people know that Matuszewski was the author of the text of Sikorski’s open speech to the country, from the beginning of 1940, in which the prime minister emphasized that Poland was at war with Germany and the Soviet Union.

Matuszewski’s personal relations with Sikorski were therefore good. At the same time, regardless of these contacts, Sikorski was dabbling in other activities behind-the-scenes. His aim was to accuse Matuszewski of embezzling part of the gold during the evacuation in September 1939. Matuszewski was very annoyed by this as he believed that he had done his job perfectly. But even as late as 1941 in Lisbon, he was still ready to cooperate with the prime minister, although he demanded a clear declaration that he did not commit any crimes during the evacuation of the gold. Sikorski – for unclear reasons – did not want to admit this. After the Polish-Soviet pact, the matter was forgotten, and the essence of the dispute was Sikorski’s policy towards Moscow and London. Sikorski did not disguise his animosity – he accused Matuszewski of desertion, initiated a prosecutor’s investigation, and at a communist rally in Detroit in 1942, said that Matuszewski deserved a medal from Goebbels, suggesting that he was a German agent.

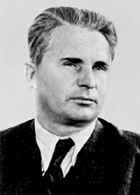

Meanwhile, in the US, it turns out that the Americans treated Matuszewski as a man dangerous to the interests of the entire anti-German coalition and brought almost totalitarian methods to bear against him.

It all begins with a month-long visit by Prime Minister Sikorski to the USA in December 1942. On 15 December, with Sikorski’s consent, Józef Hieronim Retinger, a political activist, left the delegation. He requested a meeting with the the Department of Justice and five high-ranking US officials took part. During the talks, Retinger stated that Matuszewski was conducting activities directed against an ally of America and Poland – the Soviet Union. He emphasized that this was therefore against the very foundations of the policies of the Allies, and he demanded that the Americans limit his activities.

The Americans already in the spring of 1942 had decided to register Matuszewski on the basis of the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) of 1938. It was a law giving the US government the right to control residents who were not US citizens and who in their activity represented the interests of another state. Matuszewski was therefore registered as a “foreign agent”. A whole range of actions were applied that limited his freedom of writing and his influence on Poles. His correspondence with other emigration centres was controlled. Each of his texts had to be accompanied with declarations that it had undergone censorship and was a statement made by a “foreign agent”. His apartment and the editorial offices he worked in were invaded by FBI agents. The head of the FBI himself, J. Edgar Hoover, was involved in the matter.

Americans also decided to use the so-called Polish section of the American communist movement in the US, headed by the Soviet spy Bolesław Gebert (nicknamed “Ataman”). The communist movement was thus unleashed to fight the anti-Soviet Poles led by Matuszewski. It is a paradox that Gebert, Oskar Lange, Stefan Arski and other communist activists never received the status of “foreign agent”, although they always represented Soviet interests. Matuszewski noticed this exotic alliance of Polish diplomacy with the communists and American authorities, even recognizing it as an honour that he had such influential opponents. Activities aimed at Matuszewski lasted until the end of 1945. At that time he received a letter from the Department of Justice in which it was written that his status of “foreign agent” was now obsolete due to the formation of the Provisional Government of National Unity (Tymczasowy Rząd Jedności Narodowej).

Ignacy Matuszewski lived to see all the political predictions he had formulated become reality. In the last year of his life, what kind of future did he predict for Poland and the chances of the free world against the Soviets?

In 1945, in a conversation with his colleagues, Matuszewski said that there is no free Poland, but one cannot lay down one’s arms. At the same time, he emphasized that he had found the “key to the key”. He thought about establishment of a very wide platform for the activities of Polish immigrants in the US. Matuszewski recognized that the government in exile had great value, but the “key to the key” were institutions located in the centre of the free world – Washington, D.C. He was behind the scenes creator of the National Committee of Americans of Polish Descent, and he was also one of the founding fathers of the Polish American Congress. In 1945, he became one of the leaders of the Polish community in the US despite the fact that he did not have American citizenship or the ability to perform official functions. Therefore, he took his actions behind the scenes, believing that over time, Polish immigrants would effectively lobby the American administration. He was of the opinion that the West, especially Americans, only take into consideration strong partners, not romantic ones caught up in considerations of moral obligations towards their own country. His death in 1946 ended these plans, although in some part the Polish American Congress tried to implement Matuszewski’s assumptions in the following decades. However, it never played such a great role as Matuszewski predicted.

What is the two-volume collection of Ignacy Matuszewski’s writing published by the Institute of National Remembrance like, what do we learn from it?

Ignacy Matuszewski’s Pisma wybrane has almost two thousand pages and contains about 90 percent of the works he published in 1912–1946. It is preceded by a very extensive biographical entry that I wrote. Of course, the most important texts in these two volumes are the political ones, because they include messages and knowledge, which despite the passage of years, we can still use.

Translation: Aicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin

Source: dzieje.pl