It is easier to wipe a country off the map than to destroy its soul. In the 19th century, that truth was discovered by Russia, Prussia and Austria as the loss of independence had a mobilising effect on the Poles. It became an impulse for spreading patriotic attitudes as well as an unprecedented flourishing of national culture. When the hopes placed on generals from the Napoleonic school and politicians seeking support in Western Europe failed, poets became increasingly popular.

by Wiesław Chełminiak

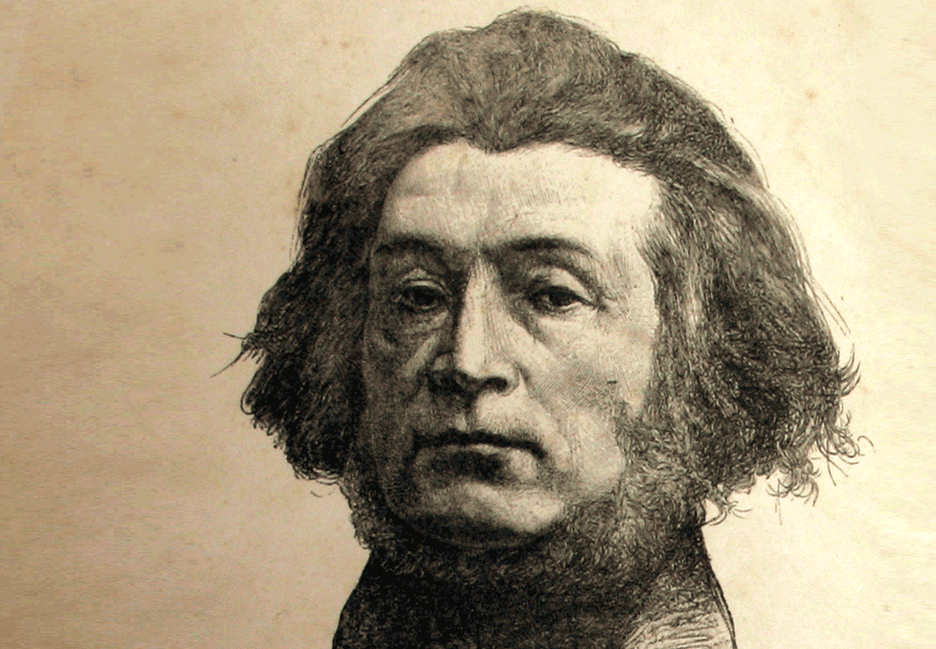

If 150 years ago the Poles were asked who was the most worthy of a monument, the answer would have been the same in each of the three parts of the partitioned country: Mickiewicz. An incorrigible romantic and eternal wanderer, the author of Pan Tadeusz embodied his battered country. His poems became an inspiration for generations of insurgents and conspirators. Russian censorship went wild in an attempt to block the dissemination of his patriotic poetic works. There was no question of erecting monuments to the poet who died in 1855. With time, the resistance of the partitioning powers decreased, but the civil committees initiating and supervising the construction of the monuments and the sculptors found themselves under enormous public pressure. They were expected to produce inspired works, granite or bronze equivalents of his Ode to Youth.

A bard hidden behind a fence

The first city to have a statue of Mickiewicz was Poznan. Unlike Warsaw or Cracow, the capital of Greater Poland could be proud of the fact that the poet visited it, and twice at that. The people of Poznań, who were subjects of the Prussian king, took advantage of the fact that liberals, who were a bit more friendly to Poles, came to power in Berlin.

The statue was forged by Władysław Oleszczyński, a veteran of the November Uprising living in Paris. Referring to the poet’s known aversion to faux-antique sculptures, he dressed Adam in frock, according to the canons of the fashion of the day. To make him look more dignified, he hung over his shoulder a coat resembling a Roman toga. In one hand, the stone Bard held a stylus, in the other a list of his most important works. It was not an outstanding work of art, but became a model for the next monuments of Mickiewicz.

It was financed from voluntary donations. It is said that the largest sum was donated by Konstancja Łubieńska, who years back had gladly accompanied the poet’s during his stay in Greater Poland.

The Prussian authorities made sure that the monument was not too visible, ordering its placement in the garden at St. Martin’s Church, separated from the street by a fence. It was unveiled on 7 May 1859, less than four years after the death of the author of Dziady [Forefathers’ Eve]. Soon, regardless of the official bans, the Poles moved the statue closer to the street. A crowd of patriots would often gather near it and shouted anti-German slogans. In 1904, the stone monument was replaced by a bronze cast and two children’s figures were added to it. The original was placed in the courtyard of the Society of the Friends of Science.

Four competitions and a funeral

The Cracovians did not want to be worse and established their own Committee for the Construction of the Mickiewicz Monument, whose task was also to bring the poet’s remains to the country and bury them in the royal crypt on Wawel Hill. Before these efforts were crowned with success, a record of quarrelsomeness and organisational sloppiness was broken in the former Polish capital. It took 25 years after the Committee was established to inaugurate the monument!

None of the projects submitted for two consecutive competitions gained widespread recognition. ‘Mickiewicz holds a quill pen in his hand in seven cases, in one he looks like a speaker, in one he looks like a Roman emperor, once – as if he were throwing banknotes, once – as if he were spreading copper coins around, several times as a reciter, once he looks down embarrassed, once he makes a face as if he were learning how to dance, once he is shown sprawling on a chair, once he asks “why did I come here, poor me?”, and once he is a complete madman,’ the famous writer Boleslaw Prus commented mockingly in a Warsaw newspaper.

The Committee therefore decided to resolve the problem in a different way: it turned to Jan Matejko. Considered an oracle in matters of patriotic art, the painter was supposed to draw up a sketch according to which three artists indicated by him would make models of the monument and the best one would win. Unfortunately, the inspired vision of the Master could not be translated into the language of the sculpture.

After the fiasco of the ‘Matejko’ competition, the ‘final’ contest was announced. The winner was Cyprian Godebski, whose father took part in the November Uprising, emigrated after its fall and knew Mickiewicz well.

The artist lived in Paris and had the reputation of a womaniser, but did not complain about the lack of orders. His sculptures decorate casinos in Monte Carlo, the arsenal in Vienna and the townhall in Brussels. He created countless busts, monuments and tombs of famous people. However, the Cracow Committee – for reasons known only to it – chose the design of Theodor Rygier, who lived in Rome and had no previous experience with monumental art. The malcontents started to say that ‘Mickiewicz awakening the genius of poetry’ by Antoni Kurzawa was much better. However, that artist was short-tempered. When he heard that his project won only the third prize in the competition of the Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts, he went mad with anger and smashed it to pieces. Kurzawa’s career also soon collapsed, he became an alcoholic and died in a poorhouse.

In 1890, the author of Pan Tadeusz [Master Thaddeus] was buried at Wawel Castle, while his Cracow monument still existed only on occasional postcards. There were even arguments about its location. Further amendments were forced on Rydygier, but it was only on 26 May 1898 that Wladyslaw Mickiewicz could unveil his father’s monument. The figure from the pedestal seemed to him similar to the infamous emperor Nero. In his diaries, he wrote that the whole statue should be given away for remelting. With time, Cracow’s residents got used to the monument, as did the Parisians to the Eiffel Tower cursed by the artistic elite. Standing in the Main Square, ‘Adaś’ – as it is affectionately called – has become one of the most popular Polish monuments, with tourists, lovers and truants hanging out around it.

A silent crowd, a screaming crowd

Meanwhile, in Warsaw, which was under pressure from Russification, things went very quickly. The new general governor, Duke Aleksander Imeretyński, not only eased censorship and allowed Polish prayers in schools, but also agreed to honour the poet who had been banned before. He designated a prestigious place for the statue: on the former royal route, near the Castle Square. The social committee, headed by Henryk Sienkiewicz (who would receive the Nobel Prize for Literature in seven years’ time), announced a national collection. There was no time to organise a competition, so the execution of the monument was entrusted to Godebski, spurned by Cracow before. The Committee chose the most modest of the three presented designs. The sculptor renounced his fee and covered part of the construction costs himself.

On the centenary of Mickiewicz’s birthday, on the morning of 24 December 1898, a crowd of freezing locals gathered in Krakowskie Przedmieście Street. Only the holders of invitations were allowed to enter the square, which was cordoned off by the Cossacks and the Russian police (12,000 were distributed). The poet’s daughter Maria came from France. However, Imeretinsky forbade speeches. At ten o’clock, the orchestra played Stanisław Moniuszko’s Prayer. The curtain was removed from the monument and all men spontaneously took off their hats. The sounds of the polonaise from Halka resounded, but the ceremony did not last even a quarter of an hour. ‘The human wave stood still in front of the monument, and so quietly that the sounds of distant bells, never to be heard from the roofs, were flowing down on it,’ remembered Zygmunt Wasilewski, Secretary of the Committee. The touched Warsaw residents could now see a four-metre-tall bronze figure, in frock and coat, with its right hand held to its chest. The inscription on the pedestal simply proclaimed: ‘To Adam Mickiewicz – his compatriots’.

On 30 January 1968, students gathered at the monument, protesting against the decision of the communist authorities banning the theatrical performance of Mickiewicz’s Dziady, allegedly undermining friendship with the USSR. That time around, the square was not quiet.

A Bolshevik hit by lightning

At the beginning of the 20th century, the monuments of the great romanticist were erected en masse in the Austrian-controlled section of the partition Poland known as Galicia. After gaining autonomy, the Poles felt the territory had been returned to them. In the provincial capital Lwów, the monument had to be particularly impressive. Consequently, it was decided that it would refer to the Warsaw column of King Sigismund III Vasa. The author of the design Antoni Popiel, a professor of the local technical university, placed a burning candle on top of the column, and at its foot the Bard, to whom the winged genius of poetry reaches out handing him a lyre symbolising inspiration.

Scheduled for three days, the celebrations began on Sunday, 30 October 1904, with a solemn mass in the cathedral. The laying of wreaths in St. Mary’s Square alone took two hours (socialists, as representatives of the poorest, laid a wreath of thorns). Representatives of the nobility, peasants, workers and youth spoke under a 21-metre-high granite column brought from Italy. Władysław Mickiewicz arrived, to whom the Galician Sejm granted a lifetime allowance in recognition of his father’s accomplishments. When Popiel asked him how he assessed the monument, he diplomatically replied that it was better than the Cracow one.

Jews, Armenians, Germans and Czechs also took part in marches, performances, concerts and banquets in honour of Mickiewicz, as Lwów and its surroundings were inhabited by a veritable mosaic of nations. The celebrations were boycotted only by Ukrainians. When, a dozen or so years later, fights broke out in the eastern part of Galicia, in the towns they conquered they overthrew the statues of the Bard, whom they hated as a symbol of ‘lordlike Poland’.

The author of Crimean Sonnets had never been to Lwów and was associated with Vilnius from childhood. It irritated the Russians. On the centenary of Mickiewicz’s birthday, they erected a monument to the executioner of the January Uprising Mikhail Muravyov and a few years later to the tsarina Catherine II, the main perpetrator behind Poland’s partitions. It was only after the country regained its independence that the Vilnius residents were able to take care of the commemoration of their countryman. The poet’s first monument, or rather its wooden model, was created by Zbigniew Pronaszko on his own initiative. However, nobody liked the cubist statue in the city, it was called a ‘ghost’ and a ‘Bolshevik’. The insulted sculptor left Vilnius and the model standing by the river was destroyed by a flood (according to another version, it was burnt by lightning).

The critics breathed a sigh of relief yet another shock awaited them as the competition for the ‘real’ monument of the Bard was won by Stanisław Szukalski. The artist, seeking inspiration in exotic art, planted a skinned Mickiewicz on top of a pre-Columbian pyramid and gave him an eagle, drinking blood flowing straight from the poet’s heart, to accompany him. In the next competition, the first prize went to a more conservative design by Henryk Kuna. A book in hand and looking into the sun, the monumental 17-metre-tall Mickiewicz (including the plinth) did not arouse controversy, but there was no happy end because of the owner of the selected plot of land in the centre of Vilnius who did not want to give it up or sell it. The monument was finally erected by the Lithuanians in 1984. The bas-reliefs with scenes from Dziady, which Kuna managed to perform before the war, were installed in its base.

The Lwów monument is the only one that has survived to our times in an unchanged form, although the city now belongs to Ukraine. The rest was destroyed by the Germans. The Cracow one was reconstructed, at the same time refining the poet’s facial features. In Poznań, the romantic Mickiewicz was replaced by a modernist one. The location is exceptionally prestigious – on the square which was previously named after Stalin. Even earlier, a monument to Bismarck stood in this place. The German Chancellor had an established opinion about the Poles. He claimed that ‘they are poets in politics, and politicians in poetry’.

Author: Wiesław Chełminiak

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin