In 1928, at the Olympic Games in Amsterdam, Halina Konopacka won the first gold medal in the history of Polish sport. In the 1920s, no woman in the world could throw the discus further than she did. A versatile sportswoman, she won the “Przegląd Sportowy” poll twice for the best sportsman in Poland (1927 and 1928).

by Piotr Bejrowski

According to the ancient rules, women were forbidden from participating in sports competitions. However, with the resurgence of the modern Olympics in 1896, there was a gradual departure from this restriction. Women began to compete in sports such as tennis, golf, archery, figure skating, and swimming. It was not until the Olympic Games in Amsterdam, which holds special significance for the Polish national team that female athletes were allowed to participate. Before this, women had their own competition for running, jumping, and throwing, known as the Women’s World Games, which were held every four years between 1922 and 1934. In 1926, Polish women made their debut in Gothenburg, where Konopacka achieved victory in the discus throw and won a bronze medal in the shot put with both hands. At the same event, she also placed eighth in the high jump and javelin throw with both hands. Four years later, in Prague, she repeated her success in her specialty event, the discus throw.

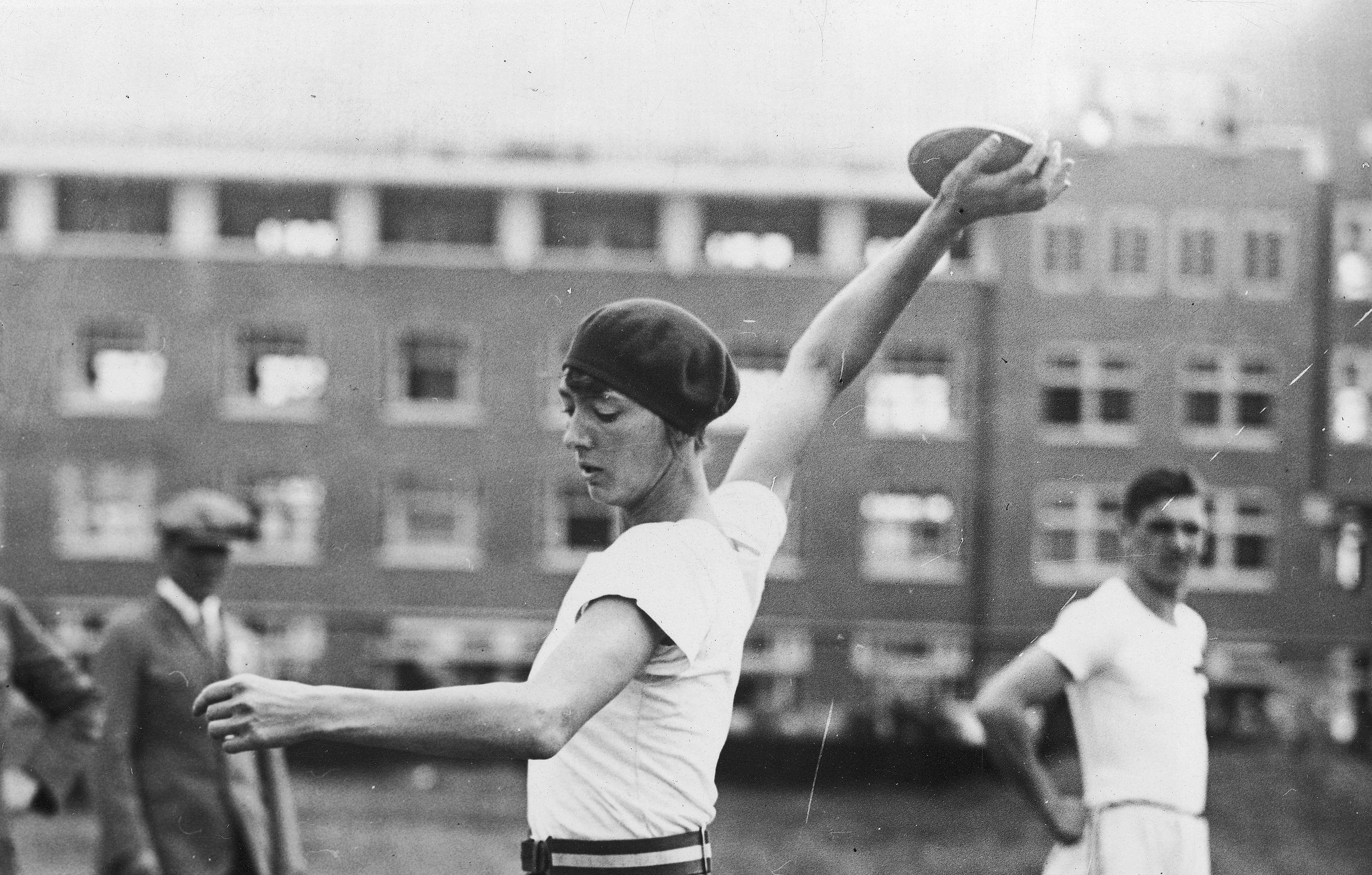

Born on February 26, 1900, in Rawa Mazowiecka, which was then under Russian rule, Halina Konopacka grew up in a family fascinated by sport. Twenty-eight years later, as a representative of the University Sports Association of Poland in Warsaw, she had already succeeded in the women’s Olympics in Sweden. She was the frontrunner for Olympic gold in the Netherlands. According to “Przegląd Sportowy”: “One cannot expect any successes at the Olympics, apart from Konopacka, of course.” So it was. Despite the rain and a nervous start, she not only won the gold medal with a throw of 39.62 meters but also improved her world record and beat second-place finisher Lilian Copeland from the USA by more than 2.5 meters. Konopacka herself recalled: “I don’t know if any of my competitors started throwing with such a strong desire to win.” Then, in the presence of 20,000 spectators, the Polish anthem was played in the stadium in Amsterdam, marking the first time it had been played on such an occasion since 1927.

The Olympic champion was a woman of exceptional beauty and radiance, standing over 180 centimeters and moving with great grace. She owed her success primarily to excellent technique, not “manly strength.” Western journalists dubbed her “Campionissima” and bestowed upon her the title of Miss Olympics. One journalist eloquently described her: “Her perfect physical condition, beauty, grace, and demeanor in the stadium – makes her one of the most aesthetically pleasing figures in contemporary sport.” As “Kurjer Warszawski” reported, after the victory, “her name is on everyone’s lips, probably even those who are not interested in sport either now or in the future.” Upon her return to Poland, she was welcomed by Marshal Józef Piłsudski, who reportedly said to her: “Ah, you won a gold medal for us in Amsterdam! That is good! It serves Poland!”

The first lady of Polish sport was not only a remarkable athlete but also a true Renaissance personality. She played the piano and guitar and enjoyed cinema, theater, and dancing. Despite not having a formal education, she knew several languages, wrote poetry, and was an accomplished painter.

In 1928, she participated in the Polish track and field championships, competing in an impressive ten events. In addition to her expertise in discus throwing, she excelled in tennis, skiing, swimming, and basketball and even participated in car rallies. Her introduction to the discus took place by accident. She held it in her hand for the first time and threw it in 1924. Progress and success came quickly. Within two years, she had become a world record holder, remaining unbeaten by any competitors during her career. She retired from her relatively short athletic career in 1931. She left the discus in good hands. Her successor Jadwiga Wajsówna (1912–1990) was the first woman to throw over 40 meters and won two Olympic medals: bronze in Los Angeles (1932) and silver in Berlin (1936).

In the year of triumphant Olympic victory, Konopacka found companionship in Colonel Ignacy Matuszewski (1891–1946), the Polish envoy in Budapest, Marshal Józef Piłsudski’s favorite, later the Minister of the Treasury, and one counted among the so-called the “faction of colonels,” a group of Piłsudski’ strusted confidants following the May coup. The wedding took place in December 1928 in Rome. As a politician’s wife, she was less and less likely to focus on sports. Thus, the Amsterdam and Los Angeles winner did not compete to defend her gold medal. Matuszewski understood the importance of sport and was a member of the International Olympic Committee. According to Matuszewski, sports struggles are “the most tangible, the most visible, the most easily measurable test of one’s national worth.”

Following the conclusion of her sports career, Konopacka became the editor-in-chief of the sports magazine “Start” and actively promoted women’s sports. She also played an active role in the Polish Olympic Committee alongside her husband. Her popularity and influence during that time made her a celebrity. Her prominence enabled her to inspire numerous women to play sports. During the 1930s, Women’s Sports Clubs began to emerge throughout the country, and the champion herself advised the representatives to do daily 10-minute exercises. These exercises would enable the ladies to “keep a young, slender figure, aesthetic and lively movements.”

After the outbreak of World War II, Matuszewski took on the responsibility of overseeing the export of gold accumulated from Bank Polski. As part of this operation, his wife was supposed to drive one of the loaded buses. The operation was successful, with the gold safely transported to Romania and then by train to Paris. After the fall of France, the Matuszewskis left for the United States, where they remained until the end of their lives. In the United States, the first Polish Olympic champion settled in New York and then in Florida. After the death of Colonel Matuszewski, she married Jerzy Szczerbiński, a former tennis player whom she had met in Warsaw. In her later years, she founded a ski school, painted, and designed clothes. After the conclusion of World War II, Konopacka returned to Poland three times: in 1958, 1970, and 1975.

While she was received with honors, she was not welcomed by the communist authorities due to her ties to Józef Piłsudski. She died on January 28, 1989, in the United States. A year later, her ashes were brought back to Poland. In 2018, she was posthumously awarded the Order of the White Eagle, the oldest and highest state decoration of the Republic of Poland. Although her athletic achievements may not seem impressive by modern standards, she had no equal in the world during her time in women’s athletics. By winning Poland’s first Olympic gold, the first lady of Polish sport etched her name into history and a well-earned place among the pantheon of the most outstanding Polish athletes.

Author: Piotr Bejrowski

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin