‘And Poland will exist! What am I saying? Poland already exists!’ the final words of the speech delivered on 28 June 1812 by Treasury Minister Tadeusz Matuszewicz evoked the enthusiasm of MPs gathered at an extraordinary session of the Sejm of the Duchy of Warsaw. As the 8th Regiment of Polish uhlans marching in the vanguard of Napoleon’s Grand Army entered Vilnius, abandoned by the Russian army, the Warsaw Sejm adopted a resolution establishing the General Confederation of the Kingdom of Poland.

by Jarosław Czubaty

This was to be the first step toward uniting the Duchy of Warsaw, created by Napoleon in 1807, with the Russian-controlled territories of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Confederation was to rouse Poles to action, and prove to the French Emperor their readiness to make sacrifices, and their complete unity in pursuit of a common goal. This was clearly evidenced by the approximately 100,000 Poles in the ranks of Napoleon’s army.

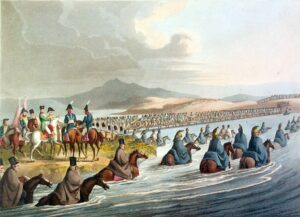

Most of them were in the Fifth Corps of the Great Army led by Prince Józef Poniatowski. A significant number of Polish light cavalry regiments were assigned to other Great Army corps. The soldiers forming them were able to carry out reconnaissance operations efficiently. Many were familiar with the war theatre, which was to include the lands of the former Commonwealth under Russian rule. Some officers, such as the commander of the aforementioned 8th Uhlan Regiment, Prince Dominik Radziwiłł, owned landed estates in these areas. Language issues were also important for the reconnaissance – Polish soldiers had no problems in obtaining information from the Polish nobility and townsmen in Lithuania. Many of them also knew Russian, or at least understood it better than most soldiers of the multinational Great Army.

Apart from the army of the Duchy of Warsaw, the Poles were represented by a regiment of light horsemen of the Imperial Guard, and four infantry regiments of the Legion of the Vistula. Taking into account also the soldiers of the units organised after the invasion of Lithuania, the number of Poles involved in the battle on Napoleon’s side amounted to approx. 120,000. Much is known about their participation in the War of 1812, especially in the Battle of Berezina, in which they made up the majority of Napoleon’s soldiers. However, they were not the only Poles who took part in this war.

A Jacobin plague?

In the face of the declared unity under Napoleon’s aegis, a troublesome political issue was the presence in the ranks of the Russian army of a considerable number of Poles serving in it not under compulsion, but of their own free will. This was not a new phenomenon. Already after the First (1772) and Second Partition (1793), the Russians – in addition to forcibly recruiting entire Polish units into their army – employed the large-scale recruitment of Polish volunteers. In an effort to recruit soldiers and officers from the Commonwealth troops, they were provided with recognition of military ranks and financial rewards.

At the outbreak of the Kosciuszko Insurrection in 1794, approx. 12,000 Polish soldiers were still in the Russian ranks – it is known that, after the defeat of the uprising, ca. 9,000 of them were disarmed and dispersed home. A little earlier, three brigades of the National Cavalry (over 2,000 soldiers) left the Russian ranks and joined the insurrectionary army. Following the defeat of the Kosciuszko Insurrection and the fall of the Commonwealth, a number of Polish volunteers still remained in the ranks of the Russian army, but did not form compact national units. Initially, requests for service from new candidates were treated with distrust, for fear of spreading the Jacobin plague in the ranks of the Russian army. Exceptions were made for those from families known for their pro-Russian sentiments.

The situation changed at the beginning of Paul I’s reign. In 1797, the recruitment of volunteers (officers and soldiers) for a Tatar-Lithuanian mounted regiment began. It included many soldiers from former Polish cavalry regiments. That same year, using the principle of recruitment, a Polish mounted regiment consisting only of Poles was formed. The structure of both mentioned units and their uniforms were modelled on the army of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The tendency to create regiments retaining a national character continued, to some extent, during the reign of Alexander I. In 1803, from the Tatar-Lithuanian mounted regiment, two separate units were created; the Tatar and Lithuanian regiments, which, in 1807, together with a Polish mounted regiment, were renamed uhlan regiments. At the same time, two more cavalry regiments were formed by recruiting mainly Poles.

Apart from military reasons, the creation of regiments that could attract Polish volunteers was also influenced by political motives. Several months preceding the outbreak of the War of 1812, the anonymous author of a memorandum addressed to Alexander I stressed the dangers of Napoleonic agitation in the Russian-controlled section of the partitioned country. In order to maintain the government’s influence over the minds of the local Polish nobility, he proposed launching the formation of further ‘national’ troops, stressing that, at a favourable point in time, they could be used to create a Polish army linked to the Russian ruler.

In the service of the Tsar

There were also other ways for Poles to enter the service: individual requests submitted to the Tsar’s military chancellery, or – in the case of younger Poles – enrolment in cadet corps in Vilnius or Grodno, in which the sons of the indigent Polish nobility were educated. After completing their education, they were obliged to serve one year in the Russian army. Interest in serving in it waned somewhat after the establishment of the Duchy of Warsaw. National hopes associated with the emergence of a rudimentary Polish state on the map of Europe, and, at the same time, fear of warfare among compatriots, dampened the enthusiasm of many candidates for service in the Russian army.

Those who found themselves in its ranks earlier likely did not share similar reservations. This is evidenced by the fact that, although the increase in the size of the army in the Duchy of Warsaw opened up career opportunities for experienced officers, the majority of those who joined the Polish Army in 1807–1811 came from the Prussian and Austrian armies. The number of officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs) from the Russian army was low. This was likely due to the greater career opportunities open to Poles in that army.

The Russian administrative and military system had long been more open to foreigners serving in the army than was the case in Prussia or Austria. They were willingly entrusted with officer ranks, and opportunities for promotion were considerable, partly owing to the lack of the necessary number of educated cadres to command a large army. Petersburg was also aware of the benefits of rewarding devoted followers, and drawing representatives of local elites, in this case the Polish nobility, into the line-of-authority network.

Some of them were very highly promoted thanks to military luck or patronage – in 1812, eight Poles were among the 550 generals in the Russian army. It is estimated that, between 1795 and 1815, some thirty Polish officers serving in the Russian army earned their General ranks. Compared to the careers of Poles in the Austrian and Prussian armies, only a few of whom reached the rank of General, the difference is striking. It can be assumed that this was also due to greater problems created by the language barrier, which Poles serving in their ranks had to overcome.

The Tsar’s promising wage

There is no doubt that financial motives played a significant role in the case of the majority of those entering the Russian military service. The former soldiers of the Polish army disbanded in 1794, or younger descendants of minor gentry families, regardless of age, rank and experience, generally had a poor education and the lack of property in common. In terms of their level of education, Poles did not essentially differ from their Russian colleagues serving in the combat troops.

Money, although extremely important, was not the only reason for the decision to undertake military service. It may have seemed an interesting and noble idea also for young men from good families – the future General Władysław Branicki stated in one of his letters that he chose the military service ‘out of vocation and preference’. This, frequently encountered, rather innocent type of motivation was connected to a youthful desire for adventure, and desire for military fame, typical of an era in which patterns of honour, as well as careers, were shaped by the battlefield. Military service attracted young people with the mirage of fame and the promise of a life full of adventure. In the case of many of them, this certainly easily pushed aside any reflection on the moral aspect of the choice they were making.

The conviction, common at the time, that military service was an important part of the upbringing of young people, may also have prompted them to join the ranks of the Russian army. As one diarist stated: ‘Youth should serve where they can, so that they are not idle and so they learn something.’ In the case of young people from poor families, military service was also a price to pay for educational opportunities. These were provided by education in cadet corps.

Family decisions on the military service of young people were sometimes, as in other periods, an act of pedagogical desperation, and the army was the last resort of desperate parents. One diary describes the case of a young man from a wealthy family, who, having been sent by his parents to Vilnius University, became famous there not for his diligence and abilities, but for his extraordinary propensity for gambling and partying: ‘Not expecting to be able to tame this turbulent character when he was young, his parents consigned him to the army, thinking that military discipline could keep him in check.’

The strength of individual motives that influenced the decision to serve in the armies of the partitioning states cannot be unambiguously determined. It is worth noting, however, that service under the command of the partitioners did not necessarily entail denationalisation or conscious denial of Polishness. While remaining a loyal Russian officer, Władysław Branicki considered himself a Pole. Sources do not mention too many demonstrations of dislike toward those who decided to serve in the Russian army. On the contrary, they were occasionally fondly remembered by their compatriots. Some of them were often valuable allies in the sometimes difficult contacts with the Russian authorities.

This uniform is not a disgrace

The average citizen of the Russian-controlled part of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth likely did not see anything improper in military service under the partitioner’s command. The applications submitted by candidates were often supported by respected personalities – Captain Gorzkowski’s application was accompanied by a letter of reference from the former Polish general, Jakub Baranowski, who had already been dismissed from Russian service at the time. An interesting aspect of this case relates to the information presented by Baranowski about Gorzkowski’s earlier service that the captain had ‘distinguished himself’ in the war with the Russians in 1792 and during the Insurgence!

The number of Polish volunteers in the Russian army is difficult to determine precisely. Some clues are provided by Dmitri Tselorungo’s research into the careers of officers of the 1st and 2nd Armies of the West in 1812. Based on an analysis of the surviving rosters, he concluded that Poles accounted for 2.7% of the 3,964 officers of both armies, i.e. 107 people. My research in Russian archives indicates that there were in fact more, because the Russian historian classified as Poles only officers who wrote: ‘Polish nobility’ in their service description in the column concerning their origin. In regimental rosters, however, numerous Polish first and last names can be found next to the information ‘a nobleman from Vilnius/Minsk, etc. Governorate’

On the basis of the review of rosters of officers of several regiments, which were organised on the Russian-controlled territories of the former Commonwealth, it can be stated that, in 1812, 64% of officers of the Polish uhlan regiment had Polish surnames; in the Tatar lancer regiment this percentage amounted to 78%; in the Volhynia lancer regiment – 38%; and in the Grodno hussar regiment – 13%. In infantry regiments their percentage was slightly lower, but still noticeable (from 13 to 30%). Service documents also contain other information that allows for identifying specific officers as Poles (the ability to read Polish, knowledge of Latin, or certificates of Polish nobility). I suppose that Poles constituted the majority among officers of the Russian army coming from Lithuania, today’s Belarus, Podolia, and Volhynia. In 1812, this group accounted for about 20% of all officers of the 1st and 2nd Armies of the West. It can therefore be estimated that approx. 396 Polish officers actually served in them (10% of all officers).

When determining the number of Polish volunteers in the Russian army in 1812, NCOs and, in cavalry regiments created by conscription, soldiers must also be taken into account. It is difficult to establish their exact number, but it must have been higher than that of Polish officers. However, an attempt can be made to indicate the upper limit of the size of the group in question. In the draft of the organisation of the autonomous Grand Duchy of Lithuania’s army, prepared in 1811 by the Poles Kazimierz Lubomirski and Jan Witt, it was proposed that the formation of the army should begin with the transfer to the Lithuanian service of the five cavalry regiments with the largest number of Poles. The plan was to use the remaining Polish officers and NCOs selected from other Russian units to form seven new lancer regiments and cadres for six infantry regiments. Lubomirski and Witt, who were likely well acquainted with the realities of the Russian army, therefore considered it possible to transfer several thousand Polish volunteers from it to the Lithuanian army.

Fear of a fratricidal war

The large number of Poles serving voluntarily in the Russian army did not arouse much emotion in the Duchy of Warsaw, as long as the alliance between Napoleon and Alexander I held. At the outbreak of the War of 1812, it was already one of the major political and military issues facing Polish supporters of Napoleon. Certainly, the movement of a few hundred or a few thousand Polish officers and soldiers to Napoleon’s side would not have decided the fate of the war. However, it could have seriously disorganised the actions of the Russian army. It would certainly also have accelerated the creation of troops formed by Poles in Lithuania. The mass abandonment of the Russian ranks by Polish soldiers would have been a political and propaganda asset as well, important for Napoleon and Poles themselves.

Certainly equally important were emotional considerations. At the very moment when a battle that would decide Poland’s future was about to begin, a return to the national banners of compatriots serving the enemy would have been entirely in line with public expectations. A proclamation addressing Poles in the Russian army was also issued by the General Confederation Council of the Kingdom of Poland. Its enactment, however, was preceded by a dispute between the members of the Council, some of whom argued that the call to abandon voluntarily accepted service, and break the military oath, was immoral and harmful: ‘Let us leave everyone free to decide according to their own imagination about the love of their homeland and honour,’ they argued. In the end, however, the proclamation was accepted. It stated that Poles pushed into the Russian army by ‘need or compulsion’ had not committed treason. However, the situation had changed: ‘The Homeland has come into being – all the duties that you undertook towards it with your first breath of life have been revived in their full force. (…) Tear off these degrading signs. Here is the true field of honour and duty.’

At the beginning of the War of 1812, some Russian generals had serious concerns about the attitude of Poles. The commander of the 2nd Army of the West, Prince Bagration, in a letter to Barclay de Tolly, emphasised his fears of the ‘disloyalty’ of the Lithuanian lancers’ regiment, which ‘will certainly not serve against its countrymen with the zeal and unanimity that befits Russian chivalry’.

Desertion to Polish banners

The course of events confirmed some of these fears. In July, despite the accompanying escort of two Russian regiments, numerous desertions were reported in the Lithuanian lancer regiment. A dozen or so soldiers from the Polish uhlan regiment escaped to Napoleon’s army, while 50 taken prisoner asked to be accepted into the Polish ranks. These events, together with a growing obsession with treason among some Russian generals, increased suspicion of the Poles. This was the reason why the Tsar’s Polish aides: Branicki, Konstanty Lubomirski and Michał Włodek, were temporarily dismissed from the active army on charges of spying for the French.

In most cases, however, Russian cavalry regiments composed of Poles fought well. A Polish uhlan regiment was even famous for a trick by which it rescued a considerable detachment of partisans encircled by the French – taking advantage of the similarity of its uniforms to those of the lancers of the Duchy of Warsaw, it played out a scene of attacking a Russian detachment in front of the French troops, took it ‘captive’, and led it to safety.

It is difficult to estimate the scale of desertion of Polish volunteers during the War of 1812. It certainly did not become a mass phenomenon and concerned, as it seems, chiefly privates and NCOs. There is no mention in the sources of those with higher military ranks deserting. One exception was the case of Captain Bykowski, adjutant to General Langeron, who – thwarting his promising career – went over to the Polish side, bringing news of Russian forces in Volhynia. In early September, Major Piotrowski, adjutant to General Rimsky-Korsakov, also crossed over to the French. Interrogated at Napoleon’s headquarters, he declared that he had abandoned the Russian service because he felt Polish, and – after reading the proclamation of the Confederation Council – decided that he could not fight against his compatriots.

However, the vast majority of Polish volunteers in the Russian army remained in the ranks of their regiments. For some, this may have been due to a lack of favourable circumstances for escape, for others – to military honour and a sense of duty. It seems that the attitude of Poles in Russian uniforms may also have been significantly influenced by a cool calculation of risk – observation of the development of events may have given rise to the conviction that abandoning the Russian service was a wise thing to do. For most of the volunteers, military service was their only source of income, too.

Their attitude in 1812 also stemmed from a kind of ethical void that followed the loss of independence. The lack of a universally accepted set of rules defining the conduct of a Pole in public life, in the absence of his own state, meant that, in many cases, they were replaced by other regulations – such as the honour of noblemen and officers. This created room for individual motivations: the desire for a career, adventure, or military glory. The modern national consciousness, defining more precisely the rules of a patriot’s behaviour in relation to a foreign power, was not formed until the later decades of the 19th century.

Polish spoken on the front

The poor response to appeals addressed to compatriots to abandon service to the enemy, provoked sharp criticism from many Poles. Nevertheless, there were friendly relations between Poles fighting in both hostile armies. During the assault on Smolensk, one of the German officers of the Great Army noticed that, during a brief break in operations, a Polish officer from the Russian army appeared before of his regiment, asking for directions to the nearest Polish unit. Directed to the posts of the Chevau-légers, he had a friendly chat with them, during which he expressed his disdain for Barclay de Tolly’s style of conducting the war marked by procrastination, and then, undisturbed by anyone, returned to his camp.

Let us complete this image with a scene from one of diaries: in 1814, after Alexander I had released Polish prisoners of war, Napoleon’s returning officers visited the diarist’s estate in the Russian-controlled part of the former Commonwealth. ‘The joy here was indescribable, they stayed for a fortnight, I shared this happiness with my neighbours and friends. Senator Iliński and General Giżycki were with us, they enjoyed themselves for two days, and the former invited us all to his estate.’ Polish Napoleonic officers and Poles in the Russian service greeting one another with a sense of exuberance – this scene illustrates well the specific situation of Poles living under the partitions at the beginning of the 19th century.

Author: Jarosław Czubaty

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki