Easter is a special holiday in Polish culture. Although most families still celebrate it solemnly today, in previous years it certainly aroused even greater emotion. Let’s take a look at how the Resurrection of Jesus Christ was celebrated in the modern era.

by Anna Wójciuk

Easter is the most important Christian holiday, commemorating the crucifixion of Jesus Christ and his Resurrection. Preparations begin with Lent, which lasts 40 days. It should be a time of penance and spiritual purification. The number “40” is derived from biblical symbolism: forty days is the duration of the Flood, Moses’ stay in Sinai and Elijah’s wandering in the desert (…), and, finally, the time that Christ spent in the wilderness.

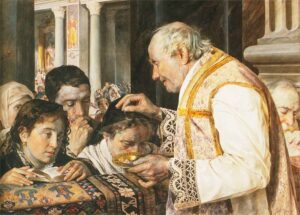

Lent begins on Ash Wednesday, which reminds the faithful that everything that is temporal will one day pass away. Thus, during the Holy Mass, the priest sprinkles the heads of the faithful with ashes and says: from dust you have risen and to dust you shall return. According to Christian tradition, the ash is prepared from burnt palm trees consecrated the previous year on Palm Sunday.

It might seem that Ash Wednesday has always been a day of reflection and melancholy. During this day some even put on penitential robes and immersed themselves in prayer. Nevertheless, Christian traditions clashed with pagan rituals when it was introduced to the Polish lands. That is why Ash Wednesday was often treated as the last day of various games, pranks and jokes. There were dancing competitions, people attempted to sprinkle each other with ashes, a straw puppet symbolizing Death was burned or melted, and chicken legs, turkey necks or egg shells were pinned to the backs [of passersby]. Ash Wednesday – as was typical of the anthropological tensions of this “time of transition” – was a bridge between the grand carnival and the spiritual preparations for Easter.

Once the games were over, all the dishes were carefully washed. Neither a trace of fat nor the taste of meat could remain on them. Today, few of the faithful observe a strict forty-day fast. Formerly it was the duty of every Christian. The most popular fasting dish was sour rye soup (Żur). It was prepared with rye or oat flour, black bread crusts and a few cloves of garlic. Żur was eaten almost every day until the end of Lent. Other fasting dishes included bread, fish, boiled potatoes, sauerkraut, eggs, and milk. Any social gatherings were forbidden, musical instruments were hidden, and rebukes issued for any loud laughter and shouting. Many believers gave up drinking alcohol. Fun and loud social meetings were replaced with common prayers.

Then came Palm Sunday – a liturgical reminder of Jesus’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem. In Poland, in order to fully commemorate this biblical event, people were struck with young willow branches. On Palm Sunday, monasteries and parish schools staged the Passion, prepared verse stories about the crucifixion of Christ and rhymed short poems about Lent and Easter. It is also worth remembering that, at that time, the Polish population attributed extraordinary power to the Easter palms. According to old Polish beliefs, crosses made of blessed palm trees ensured abundant crops and protected farmlands against various disasters.

Holy Week – the liturgical celebration of Jesus’s last earthly days – begins on Holy Wednesday. On this day, in past years in Poland, in memory of Christ’s Passion, the clergyman, after celebrating the service, would strike his breviary against the pews. It is worth remembering that on Holy Wednesday in years past, the dead were worshiped in a special way. According to tradition, fires were lit to warm their souls. The next day, a meal was prepared for them and left in bowls on the graves. Holy Wednesday was also the last day of pre-holiday cleaning. Cobwebs were swept away, dust was wiped, unnecessary items thrown out, and old brooms and clothes were burned. Along with the rubbish, it was also necessary to throw out all regrets and sorrows from one’s heart.

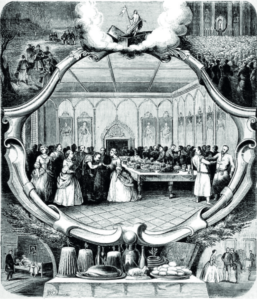

On the next holy day, Holy Thursday, rituals were performed to purify the soul and ward off evil. The soul was cleansed by swimming in a river or pond, and evil was chased away with noisy rattles. People ran around the streets making noise, thus disturbing demons. A washing ceremony for twelve old men would be conducted in the churches. Kings, magnates, and bishops would wash the feet of a carefully selected group of poor old men. Then, during the ceremonial supper, they handed them expensive gifts, e.g. coins, silver cutlery, and expensive costumes.

From Holy Thursday to Holy Saturday, the church bells were silent and were replaced with knockers. In addition, the Polish clergy would hold a service in the evenings, during which the faithful prayed by 15 lit candles. After each reading of one of the fourteen psalms, a single candle would be extinguished. The last candle was left to burn until the end, although sometimes it was extinguished as a symbol of the death of Jesus Christ. Today this service takes place in only a few churches, and is usually celebrated at dawn.

Good Friday follows Holy Thursday. On this day, there was a strict fast and a custom of visiting the “tombs of Christ” which would be prepared in churches. In addition, in line with Christian tradition, penitentiary processions were held. Penitents wore hooded robes with a veiled face and small openings for eyes and mouth. They went around all the stations, scourged themselves, and sang songs about the Passion of Christ. One of the penitents then introduced Jesus Christ. Dressed in a white knee-length robe, with a crown of thorns on his head, he carried a large, heavy cross. He would kneel at each station of the Way of the Cross. The remaining faithful, as a sign of the Lord’s Passion, scourged him, and cried, “Follow Jesus!”. The symbolism of Good Friday meant that old Polish society became fearful on this day. Evil was set free as Jesus Christ lay tormented in his tomb and the church bells were silent. Thus, the faithful had no protection.

The next day of Holy Week is Holy Saturday with the still-preserved tradition of the blessing of the food. Baskets are filled with dishes that reference the iconography of Easter or that are customarily consumed after the end of the fasting period. [In the basket,] next to the figure of a ram made of sugar or butter, there are painted Easter eggs,, hams, sausages, cakes, mazurkas, horseradish, and salt. Nowadays, Easter baskets are blessed in churches. In older times, the clergymen blessed food in manors, in rich houses with clubhouses, in rural squares, and at roadside shrines.

On Sunday night, the church bells used to sound, calling the faithful to the Resurrection. The celebration of the Lord’s Resurrection was moved to Sunday morning during the reign of Stanisław August Poniatowski. It was a manifestation of the ruler’s concern for the safe return of the faithful from the service. Up to today, however, many willing people attend the evening Easter service on Saturday evening. Commemorating the Resurrection of Jesus, Easter Sunday is the oldest and greatest Christian holiday. It is a joyful holiday that gives hope for eternal life after death. Priests celebrate a solemn Holy Mass. Then, after returning from church, the faithful sit down at the family table, share the blessed food, make wishes, and celebrate joyfully.

Easter Monday used to be a fun time in the spirit of the “coming of spring.” In old Poland, on this day everyone poured water on each other from large bowls and large buckets. Real water battles were organized, and people would even be thrown into nearby rivers and ponds. According to the old Polish custom, boys and men controlled the water on Monday. It was they who ran with full buckets, pouring them out onto girls and women. The roles were reversed the next day. On Tuesday, women poured water on the boys. One could only “save” oneself from a quick splash of water by giving a small and symbolic gift.

Author: Dr Anna Wójciuk

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin