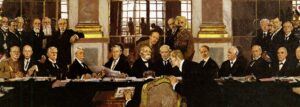

Poland turned out to be a beneficiary of the Versailles Treaty. It was among the victorious powers after the First World War and participated in peace negotiations, which was a kind of miracle of resurrection – says Dr. Piotr Szlanta, a historian from the University of Warsaw. One hundred years ago, on 28 June 1919 at the Palace of Versailles, the countries of the winning coalition signed a Peace Treaty with Germany.

Polish Press Agency: Theoretically, the most important body of the Versailles conference was the assembly of delegates. In practice, however, the United States, Great Britain, France, Japan and Italy were there to decide about the new world order. What did the Versailles peace negotiations actually look like?

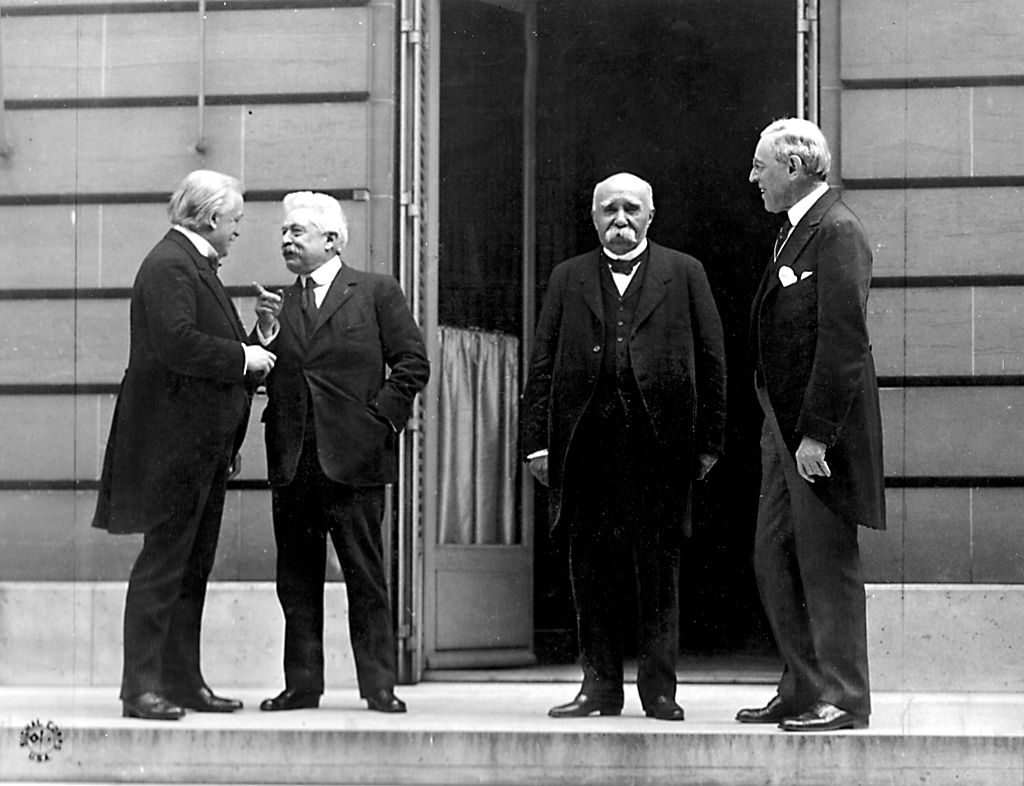

Dr hab. Piotr Szlanta: The situation was very similar to the one that took place over a hundred years earlier during the negotiating of the final treaty of the Congress of Vienna. In international relations, everyone is equal, but there are countries that are more equal, that is, they are great powers. In the case of the First World War, these were the countries that mostly contributed to the defeat of the Central Powers. Officially, they were referred to as “the main allied and associated powers.” The heads of their governments and ministers of foreign affairs sat on the Supreme Council established at the end of 1918, also known as the Council of Ten.

Over thirty countries participated in the Paris Peace Conference, while the most important decisions were made in a group of five powers, although Japan was not interested in European affairs, and was primarily focused on strengthening its influence in the Far East.

However, among the great powers themselves, there was a difference of opinion regarding the treatment of Germany. France wanted to charge Germany with reimbursement of the costs and all financial expenses incurred during the war, as well as the expense of pensions for widows, orphans or mutilated soldiers. In this way, Germany would not be able to rise and rebuild its military potential for a long time. In turn, Great Britain, which had entered the war in the name of maintaining the balance of power and preventing Germany from gaining dominance on the European continent, was interested in preventing France from obtaining hegemonic status, as it was a hundred years earlier, during the Napoleonic Wars. Consequently, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George was in favor of imposing more tolerable peace conditions on Germany, having fierce disputes in this respect with his French counterpart Georges Clemenceau, for example over the status of the Land of Sarah or Upper Silesia.

Were the negotiations held in smaller groups? What role did backstage discussions play in the final settlement?

During the peace conference in Paris, a number of committees and subcommittees debated, inter alia, issues related to the course of borders, war compensation, the future of German colonies, protection of the rights of national minorities, internationalization of ports, rivers and railways, or the identification of those responsible for the outbreak of war. At this conference, diplomats were supported by various experts, including financiers, ethnographers, geographers – who presented materials to confirm the right of a given country to take control of the territory to which they aspired.

The conference, which lasted from January 1919, gave the opportunity for numerous behind-the-scenes meetings or for discussing certain issues at evening receptions, balls or visits to the theater. However, in this type of international conference, it is quite natural that certain matters are first agreed informally, and ultimately final decisions are made by decision-makers representing the great powers.

Poland was represented in Paris by a delegation that included the Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs Ignacy Jan Paderewski and Roman Dmowski. How popular and understandable were the demands of the Polish delegation gathered in Versailles? What impression did this delegation make among the victorious powers?

The decision-makers of the Entente countries had already known a significant part of the Polish delegates. The Polish delegation was in fact the Polish National Committee, enlarged by representatives nominated by the Provisional Chief of State, Józef Piłsudski. It is worth recalling that the Committee was established in the summer of 1917 and was a kind of Polish government in exile, the highest-ranking Polish representation on the side of the Allied states. It was based in Paris, but it also had many field offices. It was recognized by the Entente states as the main representative of Polish interests. The committee was also responsible for the Polish army formed in France in the same period, known as Haller’s Army or the Blue Army. Both Dmowski and Paderewski were politicians well known and recognizable in the Western world.

The Poles’ task was also so much easier because during the war both the Central and Entente states recognized the right of Poles to self-determination. Emperors William II and Franz Joseph I announced the rebirth of Poland in the Act of 5 November 1916. In March 1917, the Provisional Government and the Petrograd Council of Workers and Soldiers Delegates also recognized the right of Poles to self-determination. After all, the person whose political concepts had the greatest impact on the international order after 1918, i.e. the President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, made his famous speech to Congress in January 1918. One of the main elements of the peace order, which was to ensure a long-lasting and stable peace after the tragedy of the Great War, in point 13, he mentioned the need to create a Poland united from three partitions, with access to the sea. Therefore, no one doubted that the Polish state should exist.

On the other hand, disputes over the shape of the country’s borders continued. It was discussed what the eastern border should look like. In eastern Galicia, Volhynia, Podolia or the Vilnius Region, Poles were, however, a minority, although they dominated in a number of clusters and towns. As for the western border, however, Poland’s right to gain access to the Baltic Sea was recognized. There were arguments about Gdańsk, which at that time was over 90% a German city, as well as Upper Silesia. It is true that Wielkopolska had already been liberated during the uprising, but its affiliation with the Republic of Poland was also confirmed by the Treaty of Versailles.

What was the strategy of the Polish delegation regarding the shape of the borders?

It was a reasonable strategy. The starting point for the discussion on the Polish borders was the border from 1772, i.e. the state before the first partition. Polish delegates admitted, however, that in the 19th century there were major demographic changes in the Eastern Borderlands, therefore the Republic of Poland was open to discussions on the course of this border. A whole range of arguments of a historical, legal, ethnographic or economic nature were used, and attention was drawn to the necessity for Poland to have an estuary of the Vistula River. As Dmowski himself argued, at the time of joining the then German Gdańsk to Poland, the ethnic relations would surely change, and the city would be quickly polonized.

In the end, Poland turned out to be a beneficiary of the Versailles Treaty. It found itself in the group of victorious powers, and participated in the peace negotiations themselves, which was also a kind of miracle of its resurrection. In one of his books, Dmowski wrote that in 1914 no one in Poland imagined that as a result of the war one of the partitioning powers, i.e. Russia, would be incapacitated, and that the great powers would oppose the other two countries who would not participate in the peace conference.

You mentioned the recognition of Dmowski and Paderewski. How did it really affect attitudes towards the Polish issue?

The mere recognition of these politicians was not a decisive argument. Of course, we cannot deny the talents of Roman Dmowski, who knew several foreign languages, and during discussions in individual committees, he freely changed the language and did not use translators, fearing that his words would be distorted. In turn, the head of the British military mission in Warsaw, who reported in March 1919 about the difficult situation of the young state due to the fact that the prime minister was a pianist. He meant, of course, Paderewski.

An important factor favoring Poland, however, was the collapse of Russia and the fact that France, in particular, wanted to create a state that would to some extent replace Russia as a buffer against Germany. Germany was perceived as an aggressive state and, after some time, always striving to rebuild its military power. Regardless of the strength of the arguments, negotiation skills and recognition of the Polish diplomats in Paris, there were also other objective factors such as the desire to create a counterbalance to Germany on its eastern border – a state that would be allied with France – that were conducive to the implementation of our demands.

Dmowski, who, together with Paderewski, signed the peace treaty on behalf of Poland, remembered this day in the following way: “Never, like in that room, has one felt the historical seriousness of the moment, for us Poles, more serious than for anyone else. On the table was the text of the treaty that Germany was to sign, the treaty recognizing the independent Polish state, by which the Germans were to return to Poland not everything that they had seized from it in the past, but almost everything that they had not managed to germanize”. Were the provisions of the treaty really so beneficial for Poland?

The provisions of the Versailles Treaty were in fact considered a success of the Republic of Poland. Of course, compared to the border in 1772, we lost part of the territory, but we gained access to the sea, and in nationalist areas, such as Upper Silesia, Powiśle, Warmia, Masuria, in accordance with the principle of the nation’s right to self-determination introduced at that time, plebiscites were planned that would ultimately decide on the nationality of these ethnically mixed territories.

I believe that Dmowski and the Polish delegation managed to get almost everything that was achievable with the balance of power at that time. Part of the lands largely inhabited by Poles, such as the Opole region or the Zaolzie region, were not incorporated into the Republic of Poland. Well, it was not us in Paris who dictated the terms. In practice, it was not possible to reconcile all of the, often contradictory, demands and expectations of the states and peoples of our region.

Despite presenting Polish postulates as moderate, the delegates of the Republic of Poland had to refute accusations about conducting imperial policy in the east.

How were these decisions received by Polish public opinion?

Generally, the opinion welcomed the result of the conference. It is worth noting that it was June 1919, as fighting for the eastern border continued, the border that had not been designated yet. The Polish-Ukrainian war over Eastern Galicia ended then, during which Polish troops pushed the Ukrainians beyond the Zbrucz River, which was the border between Russia and Austria-Hungary before the First World War. There were also disputes over the affiliation of Vilnius, into which the Polish army entered in April 1919. Moreover, there were the first fights with the Bolsheviks advancing from the east. It was rather the development of the situation on the Eastern Front that attracted the attention of public opinion in the summer of 1919. Despite attempts at the Paris Peace Conference, it was not possible to define the eastern border of the Republic of Poland. Polish public opinion, on the other hand, was hurt a lot when the so-called small treaty of Versailles, concerning the guarantee of the rights of national minorities, was forced on Warsaw. This was considered a violation of Polish sovereignty and an unjustified interference in internal affairs.

Is some aspect of the treaty negotiations still a blank spot for historians? Are there any myths around the Treaty of Versailles that make it impossible to actually evaluate the negotiations conducted at that time?

It seems to me that this treatise has already been studied in quite detail. It is hard for me to imagine that there would be any more new sources or issues to be found. Although in fact the First World War in general and the Treaty of Versailles were overshadowed by the tragedy of the First World War and the resulting shift of borders, emigration, population losses and the Holocaust.

The Treaty of Versailles was, like every peace, a compromise. On the other hand, the German side was forced to sign it under the threat of restarting military operations for which Germany was not prepared in the summer of 1919. This treaty, which was to end all wars, was the start of another conflict. Historians increasingly agree that the First and Second World Wars should be treated together, that we were dealing then with a Second Thirty Years’ War, preceded by a twenty-year truce.

In the Weimar Republic, this treaty imposed on Germany (they did not participate in its negotiations and were forced to sign it under the threat of resumption of hostilities) was referred to as the “Versailles lie” or “Versailles dictate”. Widespread opposition to its provisions united the very divided after 1918 German political scene and helped bring Adolf Hitler to power.

Interview by Anna Kruszyńska (PAP)