At the beginning of the winter of 1980, Warsaw Pact countries mobilized several divisions to take part in Soyuz-80 maneuvers scheduled on 8 December 1980. The White House was afraid that under the pretext of exercising, the Soviet army would enter Poland and break up Solidarity. Was Moscow really planning to invade Poland?

by Tomasz Kozłowski

Communist Party leaders in the Soviet Union had closely monitored the situation in Poland since the summer of 1980. Moscow was concerned about the strike wave that poured through factories in July. Leonid Brezhnev personally met Edward Gierek, the First Secretary of the Polish United Workers’ Party while on holidays in Crimea, in order to ask him about the public mood and persuade him to oppose the democratic opposition. “Comrade Brezhnev, we have a hold on the opposition – reassured Gierek – the government has the situation under control.”

Two weeks after their conversation, the largest wave of strikes in history took place in Poland. At the climax, as many as 700,000 people protested! Until the end of his life, Brezhnev did not understand how Gierek could have made such a mistake: “What happened? Was he too reckless, too confident? Is it because of his ambition? I do not know”. The Soviet Politburo unexpectedly faced one of the most serious crises in the history of communism. A special commission to assess the situation was set up headed by Mikhail Suslov, a party veteran, who for 30 years was responsible for ideological problems. The team included representatives of the most important institutions: KGB chief Yuri Andropov, Defense Minister Dmitry Ustinov and Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko.

At the end of August 1980, the situation in Poland was close to a general strike. The members of the Suslov Commission feared the worst, so they developed a plan of military preparations. They proposed to mobilize three armored divisions, to stand ready to assist the Polish Army in suppressing strikes. However, every possibility was prepared: “If the main forces of the Polish Army move to the side of the counter-revolutionary forces, we must increase our forces by another five or seven divisions.” In the worst-case scenario, the Soviet army was to appoint an additional 100,000 reservists and prepare 15,000 machines.

The Polish United Workers’ Party leaders were aware that they had lost control and felt trapped due to the scale of social rebellion. Gierek feared both a general strike and foreign intervention. In confidential conversations, he indicated that the entry of the Warsaw Pact troops into Poland was possible: “there is such a possibility, because the situation disrupts the work of the [socialist] bloc, they are entitled to intervene in Poland to defend the system and economic and political interests.” Such a development was also feared by Stanisław Kania, an important member of the Political Bureau, responsible for the supervision of, among others, the secret police. Under such pressure, the government eventually signed agreements with the strikers. This led to the end of the strike wave and opened the way to the creation of “Solidarity”.

Intervention costs

The establishment of “Solidarity” worried leaders of other Warsaw Pact states. They feared that the revolution would cross Poland’s borders and “infect” their citizens with the freedom bug. The Soviet Politburo considered various options, including an intervention similar to that in Hungary in 1956 or in Czechoslovakia in 1968. This would, however, be opposed by the international community, it was an expensive operation, and its effects were difficult to predict. No one could predict the scale of the resistance of Polish society and whether Polish soldiers would turn against the invaders.

The Soviets preferred to solve the problem without getting their hands dirty: they began to persuade the Polish authorities to introduce martial law. According to Brezhnev, this seemed like a good solution. Defense Minister Dmitry Ustinov was even more determined: “If martial law is not introduced, the situation will become very difficult and even more complicated,” he explained during the Politburo meeting. However, both he and the head of the KGB Andropov were convinced that it was impossible to get involved in the Polish conflict militarily. “We must stick to our strategy: our troops will not be sent to Poland,” emphasized the head of the KGB.

Polish communist party leaders – or at least most of them – also feared the effects of external intervention. This topic was avoided during the meetings of Polish leadership – it was feared that some participants of the Polish Political Bureau sessions might pass on what was discussed to their “comrades” from neighboring countries (years after, the opening of the archives of the East German SED confirmed these allegations). However, trusted advisers to the newly elected First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party, Stanisław Kania, and Minister of National Defense, Wojciech Jaruzelski, prepared secret analyses of the Soviet intervention. In one of them we read:

The invasion of Soviet troops will trigger a counterattack by some Polish military units, which will probably refuse to obey their commanders in such a situation (…). The Soviet troops will also have to break the armed resistance of multi-million workers’ crews, which will be accompanied by spontaneous but doomed actions by some youth. This resistance to the superiority of the Soviet troops will be overcome quite quickly, giving rise to bloodshed and the number of victims ranging from 100,000 to 500,000 (…). The occupation will have to be extended, requiring the permanent presence of about 30 to 50 divisions in Poland (…). In other words, intervention in Poland, as opposed to a regular war with clear strategic goals, may rather result in a process of long-term military entanglement without any practical strategic benefits, and at enormous political and financial costs.

Both Warsaw and Moscow were afraid of such a scenario. That is why the Soviets wanted to convince the Polish leadership to introduce martial law on their own. The problem was that – as Stanisław Kania explained, “martial law means that we want to break Solidarity arresting people. You have to be aware of the consequences. Then the economy will be threatened and there will be strikes. What happens next if the street is re-occupied, the street will not calm down by persuasion. We run out of possibilities to solve it on our own.” In other words, Kania was afraid that an unsuccessful attempt to introduce martial law might end up with Soviet intervention anyway.

5 minutes before zero hour

For the next few weeks, a game continued between Warsaw and Moscow in which Brezhnev tried to force the Poles to overcome their fear and fight against their own fellow citizens. On 26 November 1980, the Political Bureau of the Polish United Workers’ Party even considered such a possibility, several of its members urged them to take decisive action against “Solidarity”. However, no final decisions were made. Information about this reached the Kremlin. The Soviet Politburo decided to convince Polish “comrades” to take bolder decisions. On 5 December 1980, a meeting of the Warsaw Pact Political Consultative Committee was convened, to discuss the “issue of Poland”.

At the same time, Nikolai Ogarkov, Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the USSR, convened a meeting on 1 December 1980, with the participation of representatives of the army of three satellite states: East Germany, Czechoslovakia and Poland. He said the decision was made to conduct Soyuz-80 exercises to “demonstrate readiness to defend socialism” which was scheduled for 7 December 1980.

The preparations for the exercises worried the White House. The CIA director alerted on 2 December: “I believe the Soviets are preparing their forces for military intervention in Poland. We do not know, however, whether they have made a decision to intervene, or are still attempting to find a political solution”. A day later, President’s Assistant for National Security Affairs Zbigniew Brzeziński, Secretary of State Edmund Muskie, Secretary of Defense Harold Brown and Director of Central Intelligence Stansfield Turner discussed the situation in Poland: “Brzezinski pointed out the serious consequences that a Soviet invasion would have for East- West relations. In many ways it would set things back to the ’50s.”. They agreed on a warning that President Carter was to convey to Brezhnev.

Carter wrote in his memoirs: ”I sent Brezhnev a direct message warning of the serious consequences of a Soviet move into Poland, and let him know more indirectly that we would move to transfer advanced weaponry to China. I asked Prime Minister [Indira] Gandhi to pressure Brezhnev (who was about to visit New Delhi), and warned the opposition leaders in Poland so that they would not be taken by surprise. I and other administration officials also made public statements about the growing threat to European stability”.

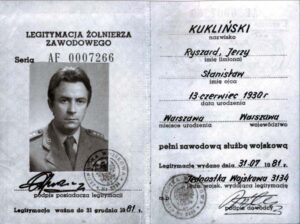

The CIA had one ace up its sleeve – a spy in the General Staff of the Polish Army. Back in October, the head of the KGB warned not to share too much information with Polish “comrades”: “If we provide the materials, it is possible that they may reach the Americans.” His suspicions were correct – Colonel Ryszard Kuklinski immediately reported that preparations for the intervention had begun under the guise of military maneuvers. On the basis of his reports, the chief of the CIA warned President Carter on 5 December: “Moscow has developed a plan for intervention in Poland (…). The intervention is to take place under the pretext of joint Soviet, East German and Czechoslovak exercises in Poland. Readiness to cross the Polish frontiers was set for 8 December.”

The Polish leaders who came to Moscow for the meeting of the Warsaw Pact Political Consultative Committee were also scared by the prospect of a possible intervention. Wojciech Jaruzelski recalled: “I knew the atmosphere of this type of meeting (…). Always a little relaxed at the beginning – greetings, hugs, chats. This time it was stiff.” One of the members of the Polish delegation looked so nervous that Konstantin Rusakov, secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU responsible for contacts with allied parties, approached and began to reassure him: “he said that there is no need to worry, everything will go well.”

The meeting was opened by Brezhnev: “Naturally, the crisis in Poland worries all of us. All kinds of forces have become active against socialism, from so-called liberals to supporters of fascism. They struck a blow to socialist Poland. Its aim, however, is the entire socialist community.” Stanisław Kania tried to answer. He pointed out that one must act wisely in order to avoid “a bloody confrontation the consequences of which would have an impact on the entire socialist world.” At the same time, he assured that the Polish authorities would defend socialism. Some leaders, such as Nicolae Ceaușescu, were quite sympathetic to the arguments put forward. However, the leaders of the GDR and Czechoslovakia were very critical.

Brezhnev summed up the discussion: “The situation in Poland and the danger over Poland are not only Polish matters. This is true for all of us. We will never forget that 600,000 Soviet soldiers died on Polish soil, fighting to defend Poland against fascism and for its freedom. The blood of the Soviet people and the blood of the Poles poured out in the sacrificial liberation struggle. Opponents of socialism, both in Poland and abroad, must know that the socialist friends and allies of the Polish People’s Republic will not abandon it in its need.” It sounded ominous, but meant that the Soviet Union would refrain from resorting to a military solution. The First Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU assured Kania behind the scenes: “Well, we will not enter. And when it gets complicated, we will enter. We won’t enter without you.”

Members of the Polish delegation, especially Kania, were convinced that their attitude significantly contributed to the fact that the invasion was kept away. Washington thought the same about its diplomatic efforts. Zbigniew Brzeziński assured President Carter that the most important “was the effectiveness of the Western counter propaganda campaign which convinced the Kremlin that the West would retaliate ‘massively’ with political and economic sanctions”.

Ghost invasion

Few people indicated that this assumption was wrong. Marshall Brement, serving on the National Security Council as Soviet adviser to the President, wrote in December 1980 to Brzeziński: “As you know, I take a different view. The difficulties which would face the Soviets if they actually invaded Poland (international reaction, compounding Soviet economic weaknesses, possibility of armed Polish resistance, downgrading of Warsaw Pact forces, inability to predict the ultimate consequences, etc.) are fairly obvious and are not worth repeating here. Because of such difficulties, I do not think the Soviets will move in Poland until they are completely convinced that the Polish leadership has little if any chance of handling the situation in a reasonably satisfactory manner”. Brement hit the nail on the head.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Valery L. Musatov, an employee of the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the apparatus of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party, stated that “our actions were characterized by great flexibility and realism. Using the threat of direct interference, which was feared by both the authorities and Solidarity, we consequently got rid of some anti-opposition activities. Naturally, it was not mentioned directly.” Wiktor Kulikow, the commander-in-chief of the United Armed Forces of the Warsaw Pact, claimed that “the political leadership was categorically against the entry of our troops into Polish territory.”

Today it can be said that the Soviets did not plan to invade, but wanted to create a tool of political pressure on the authorities in Warsaw as evidenced by several events. In 1968, the invasion of Czechoslovakia, smaller than Poland, was carried out by 30 divisions. In the Soyuz-80 maneuvers, 18 divisions were to be taken – not enough to take control of the situation without cooperation with Polish units, whose reaction Moscow was not sure of. Documents from the East German and Czechoslovak armies mention an even smaller number of units being prepared.

The sense of such an intervention, which could tie the Soviet army in the long-term occupation of Poland, was in question. Moscow decided to involve in the Afghan operation, which – contrary to previous analyses – was prolonged and tied up more and more forces and resources. In this situation, it is also difficult to suspect that Brezhnev would have decided to engage in another conflict on the international arena.

The Politburo consistently adhered to the principle of non-intervention. The head of the KGB persuaded to resolve the conflict with the hands of Poles. In the fall of 1980, he explained: “We must, however, stick to our strategy: our troops will not be sent to Poland.” A year later, he went even further: “We can’t take any risks. We do not intend to introduce troops to Poland. This is the correct attitude and we must stick to it to the end. I do not know how the case with Poland will develop, but even if Poland is under the rule of Solidarity, it won’t get any further. But if the capitalist countries attack the Soviet Union, and they already have appropriate agreements on various types of economic and political sanctions, it will be very difficult for us. We should show concern for our country, for the strengthening of the Soviet Union”.

Is the assessment of the events of December 1980 important from the point of view of Polish history? It seems so. It shows that the Politburo planned from the very beginning – through political pressure, disinformation and the use of the “intervention bogey” – to push Polish leaders to introduce martial law. In the long run, it was as a result of this strategy that the Kremlin was able to solve its problem with Polish hands.

Author: Tomasz Kozłowski – PhD in political sciences, employee of the History Research Office of Institute of National Remembrance

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin