Unexpected high price rises announced by the communist authorities of the Polish People’s Republic in December 1970 led to an outbreak of social discontent and street protests. The authorities did not enter into talks and proceeded to brutally suppress the strike.

by Piotr Abryszeński

Rails are growing cheaper!

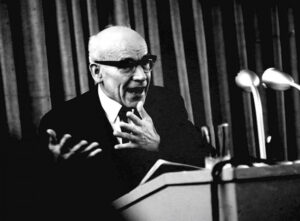

For Władysław Gomułka, the final month of 1970 began with the personal success he had fought for over the last few years. After almost a year of talks, on 7 December, in the Column Hall of the Council of Ministers in Warsaw, a treaty was signed with Germany on the normalisation of mutual relations. A quarter of a century after the end of the Second World War, the border on the Oder and Lusatian Neisse was officially recognised.

Meanwhile, in the secrecy of the political cabinets, preparations for the change of prices in the country had been under way since 1969. It is untrue, therefore, that the decision to raise prices was taken by the party leadership euphorically after the signing of the agreement with Germany. Whether the decision-makers had planned to take advantage of this fact, counting on a softer reaction from society, remains an open question. In any case, the party prepared a special letter for the occasion, which was to be read out at party meetings on 12 December. In the largest work establishments, such meetings were attended by representatives of the central authorities. However, ordinary party members had to play the role of cushioning the first wave of negative emotions.

In the command economy, not only production plans and all investments were approved by the government. The price list for products was also fixed and imposed from above. This led to a fall in economic efficiency, and necessitated periodic price regulation. In a capitalist system, prices are regulated by free market mechanisms. Under real socialism, society was periodically affected by ‘silent price hikes’, which worsened the already difficult situation of Polish households. That time, however, the increase was drastic. The prices of foodstuffs, building materials, textiles, and fuel, went up. On the other hand, the prices of industrial goods, TV sets, radios and… railway rails, were lowered.

At meetings, people reacted apathetically, although some accepted the authorities’ decision with tears in their eyes. Others laughed uproariously – perhaps the worst omen for those in power. In any case, the increase was all the more painful because it was introduced unannounced, just a dozen or so days before Christmas, when people were preparing for their Christmas shopping.

‘To the Committee building!’

Workers on the morning shift at the Gdańsk Shipyard, who turned up for work at six in the morning, were still in the changing rooms discussing the price change carried out by the authorities. Initially, some workers of the S-4 department did not start work. Information about the strike in this department reached other crews, who interrupted their work demanding meetings with the management. Some 2,500 people gathered at an improvised rally in front of the management building.

The shipyard director, Stanisław Żaczek, appeared and told the assembled that the only thing he could do was to arrange for an increase in bonuses. In response, he heard: ‘You are not going to help us here anyway, and we have no complaints about you – let the one who decided about the increases come.’ At one point, the crowd called out: ‘We are not going to stand here – we are going to the Party Provincial Committee!’

According to the unanimous accounts of participants, the march was peaceful. There were even calls from the crowd not to trample the lawns. Along the route, the protesters were joined by random people, often youth. Upon reaching the Committee building, they were approached by Second Secretary Zenon Jundziłł, accompanied by a dozen or so co-workers (the First Secretary of the Committee, Alojzy Karkoszka, attended the plenum of the Central Committee in Warsaw). However, dialogue proved impossible – the communists in power avoided any specifics. The protesters attempted to reach the local headquarters of the Polish Radio, and broadcast their message to the whole country; they also sought support among students of the Gdańsk University of Technology.

There was growing fatigue and irritation among them at having their demands ignored. At around 4 p.m., the protesters returning from Wrzeszcz encountered a small number of ZOMO (Motorised Reserved of the Citizens’ Militia) troops in Błędnik. The first confrontation took place then. Of course, both sides of the clash attributed the initial use of force to the opposing side. It was most likely the militia that provoked the strikers by shooting at them with tear gas bullets. Stones and iron bolts were thrown from the crowd. From that moment on, events moved very quickly.

Fighting in the streets of Gdańsk lasted until evening. The city was plunged into chaos. In the evening, the building of the Voivodship Committee, contemptuously referred to by the people as the ‘Reichstag’, was set on fire. Barricades were erected, shops demolished, and cars burnt. At least several dozen were injured. Of course, protest participants feared reprisals and rarely reported to hospitals.

The following day, i.e. on 15 December, the mass media were silent about Monday’s events. Only the margin of the first page of Głos Wybrzeża carried a short text blaming the workers for the protest. It attributed aggression to them, and labelled them ‘irresponsible elements’. The article may have contributed to the growing discontent of the people on the Baltic Coast. Early in the morning, most of the Gdańsk plants did not resume normal work, and sit-ins were launched at some. Shortly after 7 a.m., thousands of shipyard workers took to the streets, heading towards the city centre. Workers from many other Gdańsk plants did the same. Militia units were sent to stop the protesters. Heavy military equipment was deployed in the streets.

The fiercest fighting took place in the area between Błędnik, the main train station, the buildings of the Voivodeship Committee, and the Praesidium of the Voivodeship National Council (PWRN), as well as the Voivodeship Police Headquarters. The demonstrators began setting the headquarters of the hated party alight again. Some officials came out of the burning building with their hands in the air, and were stopped by the shipyard workers. Others ran up to the roof and, if they managed to grab onto ladders thrown from a helicopter, flew away from the battle area, while those who failed to do so, jumped onto mats laid out at the back of the building. Clashes with the army and police continued until late evening.

Representatives of the central authorities reacted in a peculiar way to the news of the outbreak of the strike. ‘Law and order will be established, even if 300 workers die,’ responded Zenon Kliszko, a Politburo member and Deputy Speaker of the Sejm, to the proposal of entering into talks with the strikers during a meeting of the Executive Committee of the PZPR (Polish United Workers’ Party) Voivodship Committee in Gdańsk. Another of his statements was terrifying: ‘You don’t talk to counterrevolution, you shoot at counterrevolution.’

Blood in the streets

On 16 December, army units took up designated positions in the city. The Shipyard gates were densely covered as well. This was also the sight of the shipyard workers going to work for their first shift. In spite of warnings from the army and older workers, several hundred young shipyard workers decided to leave the area and organise another march through the city streets. On the commander’s order, warning shots were fired into the air, and then at the protesters’ feet. Several dozen people fell down. Two of them were killed. Shouts of ‘murderers!’ could be heard from the crowd.

Polish flags with black ribbons appeared on all the gates of the shipyard as a sign of mourning. A sit-in was declared. In addition to the demands made earlier for the normalisation of prices, there were also demands of a political nature – punishment for those responsible for the state of the economy, the withdrawal of troops, and guarantees that representatives of the striking crews would not be punished. Despite the tightening of the protest, the situation in the city was slowly returning to normal.

The protest in Gdynia was different. It began on 15 December when workers from the Paris Commune Shipyard took to the streets, joined by protesters from other plants. The authorities there behaved somewhat differently; they did not ignore the strikers, and entered into talks. The result was the drafting of a memorandum of understanding containing demands, including wage regulation and bridging the wage gap between different occupational groups. In practice, the protest was recognised. The workers set up the Main Strike Committee for the City of Gdynia, which included representatives of the most important enterprises. They were assured that they were not in any danger. However, on the night of 15–16 December, the building was raided by militia units that brutally beat and arrested the members of the Committee, which ceased to exist after only seven hours of activity.

Black Thursday

On the evening of 16 December, television and radio broadcast a speech by Stanisław Kociołek, who called for normal work to resume. The weary workers heeded this call. At the same time, the authorities decided to block the Paris Commune Shipyard. Many historians perceive this contradiction at the decision-making level as an argument for acknowledging that the communist authorities had acted with premeditation, aiming to escalate the conflict.

On Thursday 17 December, from early morning, trains transporting shipyard workers to work arrived at the Gdynia Shipyard railway station. Meanwhile, the footbridge over the tracks leading from the station to the shipyard was blocked by the army. Megaphones informed confused people that the plant was closed, and called on the workers to withdraw. Meanwhile, more trains stopped, and those disembarking pushed against those present at the station. At around 6 a.m., the first tank shot was fired and, after a while, the army began using live ammunition.

A telling symbol of December 1970 were marches through the streets of Gdynia. One of them, in which 18-year-old Zbigniew Godlewski, killed near the Gdynia Shipyard station, was carried on a door, went down in history. According to official data, eighteen people died and hundreds more were injured as a result of the shots fired that day in Gdynia. It was believed that the violence was the communists’ revenge for the street protests in Gdańsk.

Events in Szczecin were equally dramatic that day. While the strikes in Gdańsk and Gdynia were spontaneous, the situation in Szczecin was different. The protesters were much better organised, and had much more precise goals. Following unsuccessful talks with the management of the Adolf Warski Shipyard, several groups of workers took to the streets, and – as in the Tricity – there were heavy clashes. The army was used to support the militia units, but there was good rapport between protesters and soldiers, and the slogans ‘The army with the people!’ and ‘The people with the army!’ were written on military vehicles. This did not stop the bloodshed. According to official figures, sixteen people died in the clashes in Szczecin.

A characteristic feature of the December revolt was the fact of the strongest and most dramatic protests breaking out in the major port cities in the north of the country, and young people played a huge role in them. However, the protests in Gdańsk, Gdynia and Szczecin had their own unique features. The protest in the streets of Gdańsk, initially peaceful, was nevertheless unorganised. In Gdynia, the protest was peaceful, and even the smashing of the Strike Committee did not lead to an escalation. It was only the massacre of defenceless people on the morning of 17 December that changed the course of events. That day went down in history as Black Thursday.

Funerals at night, changes during the day

On the following day, 18 December, the protest was all but pacified in the Tricity, but continued in Szczecin. Never in peacetime, apart from during martial law, had the army been used on such a scale to secure public order. A total of (including mobilised forces, not just those used directly in action), nearly 61,000 soldiers, 1,700 tanks, as many armoured personnel carriers, 8,700 cars, 108 helicopters and aircraft, and 40 Navy vessels were involved. And yet it should be remembered that approx. 9,000 officers of the Citizens’ Militia, SB (Security Service), and ORMO (Volunteer Reserve of the Citizens’ Militia) were also used to suppress the demonstrations.

According to official data, 45 people were killed, but the list of victims was likely longer. Hundreds suffered physical injuries, and had to deal with the consequences for years to come. Those arrested were subjected to real torture. They were kept in gloomy cellars, brutally beaten, and some had their heads sheared with knives. The aftermath of December 1970 was also a trauma that some people carried, and will continue to carry, for the remainder of their lives.

On 19 December, the first of the victims’ funerals took place. They did not proceed in the usual way, and were held late in the evening. Only the closest family members were informed, if at all, of the fact by officials moments before the funerals, and escorted to the cemeteries in police cars. The dead were buried at half hourly intervals. Only in one case, due to the strong protests of the victim’s family, was a victim buried during the day.

The background to the political decisions taken by members of the Politburo remains obscure. The provocation by the authorities, including the deliberate attempt to increase the number of deaths, remains unexplored. It is known that shots were fired at the unarmed crowd both from helicopters, as well as sniper rifles on top of buildings.

The Seventh Plenum of the Central Committee of the PZPR was urgently convened in Warsaw for Sunday 20 December. Its main aim was to elect a new First Secretary for the party. Edward Gierek, the former First Secretary of the Katowice Voivodship Committee, was chosen. There were also changes in the Politburo itself. Gomułka failed to attend the Sunday meeting, who had been hospitalised owing to the sudden deterioration in his health. Compared to his predecessor, Gierek evoked extremely different reactions. He had a great ability to establish contact with the public, and knew how to win people over.

The previous team was blamed for the current state of affairs, which was a type of tradition in the Communist Party. This was the only effective form of legitimising power in that system. The changes at the central level were a symbolic end to the intra-party game. As it appears, the tragic events on the Baltic coast may have been a consequence of this. On 1 March 1971, following another wave of strikes, the authorities withdrew the price rise introduced in December.

This does not mean that they were ready to expiate. They fought the memory of December 1970 in various ways, but suppressing it had the opposite effect to the one intended. The date became symbolic. The ruthlessness of the authorities towards the protesters exposed the nature of the system and, in the following years, became the starting point for opposition activity, as well as an important, albeit painful, lesson in 1980, when ‘Solidarity’ was formed.

Author: Piotr Abryszeński (PhD, employee of the History Research Office of Institute of National Remembrance)

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin