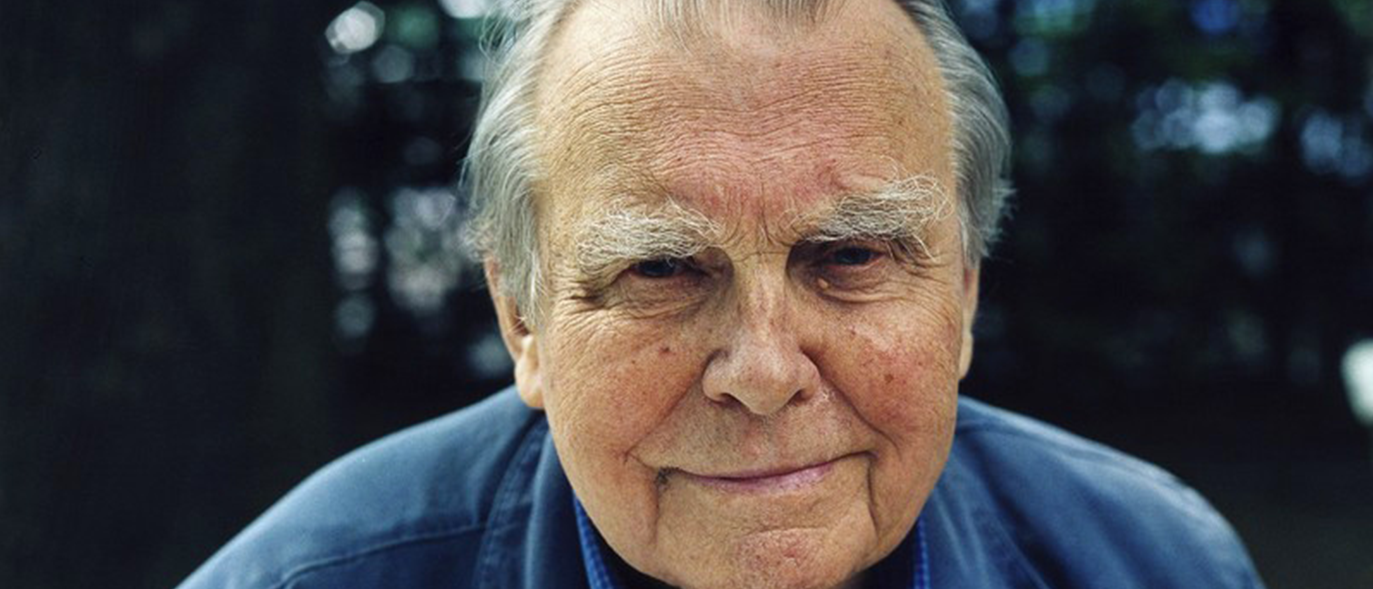

An edition of foreign-ministry reports from the US, posted decades before Czesław Miłosz, the poet and writer, received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1980.

by Klementyna Suchanow

An edition of Czesław Miłosz’s diplomatic reports from postings at the consulate in New York City then from the embassy in Washington, D.C., has been collected in the Foreign Ministry archives. One 1947 report on the burgeoning theater scene in Poland is included in English, as is the supplementary correspondence with Albert Einstein.

Title: Diplomatic Reports 1945-1950

Afterword: Marek Kornat

Publisher: Więź, Warsaw, 2014

book available in Polish

A broad collection of diplomatic reports is held in the archives of the Polish foreign ministry; the present edition is selected from this collection and brings together Miłosz’s reports. His diplomatic correspondence, written as an employee of the foreign ministry, is dispersed among various international institutions. Parts are found in the Beinecke Library at Yale, with other parts in the Einstein Archive of the Jewish National and University Library.

The first part of the documents in the new edition are personal papers about Miłosz: his application for the position, CVs and evaluations. The second part includes reports written by Miłosz from his posts as cultural attache in New York and Washington, about cultural life and promotion of Polish culture and arts, as well as the U.S. context, press reception and collaborations. The third part includes correspondence between Miłosz and Einstein, some of which is published here for the first time. The final part is Miłosz’s lecture in French about his relative, the poet Oscar Miłosz, given during his stay in Europe. The uncle was a significant person in Miłosz’s artistic development (in addition to his own accomplishments as a writer), and this is the first publication of the lecture.

Miłosz had debuted as a writer before the Second World War, as a member of a group of Polish poets who were named ‘the Catastrophists’. Regarded as one among a number of emerging poets, his primary occupation was with Polish Radio. To better understand Miłosz’s postwar decision to join the foreign ministry of a country that was becoming communist, two factors are key. One is that under German occupation there was no Polish publishing or editorial industry within which writers could realize themselves as artists and not compromise reputations or even risk their lives in retaliation for collaborating with the occupation authorities. The second is that those five years of abstaining from publishing led to an eruption even in the first postwar months. Writers had not been publishing but had been storing material in drawers or their thoughts, resulting abruptly in a flood of publication.

Yet the imposition of the communist system in Poland was also developing rapidly. For Miłosz, who’d been born in Lithuania and who’d fled Wilno (Vilnius) from the Soviets during the war, it was clear that the sovietization of Poland would mean restrictions and the imposition of censorship. Thus he had already in August 1945 applied for a position in Switzerland. By some caprice of the authorities, he was posted instead to the US. He took up the job, therefore, not from conviction but to escape oppression, attempting to secure freedom for his work as a poet.

The editions most interesting part is clearly the second one, after he and his wife arrived at the consulate in New York in January 1946. His first report embraced the period between 7 February and late March. In it he explained his main aims in his work in the States. These are informing the US and Polish societies about the reconstruction of cultural and artistic life in Poland and material aid to Poland in the cultural realm, and informing Poland about culture and artistic life and science in the States. Immediately, he stated the complication of informing the US public about the changes in Poland, due to anti-communist currents mounting in the States. He also took up the mission of translating English-language poets in the US into Polish.

He admitted later in his life that in these reports he had more latitude to objectively present the situation statesides than he could in published work, with the latter being subject to censorship at home. The authorities, in brief, would want to know the situation – but not to expose it to public awareness in Poland. Gradually the vigor of Miłosz’s range can be seen to reduce, as he saw the obstacles being planted in his way. (A constant call for more newspapers and magazines from Poland, to show the graphic design developing in periodicals as well as photo reportage of Warsaw’s rebuilding, lessened when these useful publicatons were not forthcoming.) Failures included the theater world, despite reports of an interest on the part of the International Student Theater Library to collect Polish dramas – he never received manuscripts of new Polish plays from the ministry of culture. A comic piece from Harper’s magazine about displaced persons in Poland gets a mention in the book, as does The Dungeon Democracy by Christopher Barney noting new tyranny in Poland, and an article from Encyclopedia Americana about Auschwitz. Sometimes he promoted Polish writers on the US market by providing introductions to translations including Smoke over Birkenau by Severyna Szmaglewska, published in 1947.

Miłosz’s growing disappointment in decisions about introducing new social realities in Poland, and his disagreements with developments on the political scene there, attracted the suspicion of the new authorities. They elected to bring him back to Poland, while his wife remained in Washington expecting their baby. Sensing that Miłosz was not truly following instructions from the government, the decision was taken to send him to France instead of returning him to the States. This decision provoked him to leave his post in Paris in 1951 and join the Polish emigration led by the circles around editor Jerzy Gierdroyc and Maisons Lafitte. With the publication in their emigree journal Kultura of a manifesto, “Nie,” Miłosz broke with the communists. He reinforced the Polish opposition in exile, along with the writer Witold Gombrowicz, in exile in Argentina since 1939, who in the same issue of Kultura published the beginning of his novel Trans-Atlantyk.

Miłosz’s correspondence with Albert Einstein sheds light on his moral hesitations before making this momentous decision. In a letter from 2 February 1951, he writes “Dear Professor Einstein, you remember our visit last summer and my sincere confessions that I did not know what to do – whether to cut my ties with the Polish government and stay in the States, or to accept a new assignment in Paris.” Further into the letter, Miłosz appeals for aid in his family and legal situation, even up to the president: “Help me, professor. You know how I trust you. I appeal to you in a crucial moment in my life.” Einstein replies with a willingness to help on 6 February, asking rhetorically “What has become of the freedom of intellectuals?”

Miłosz’s comments about the US reality are sharply focused and very interesting from a historical point of view. These show how a highly intelligent Polish poet and thinker was seeing American mass culture as well as failures of democratic system, in the nation that would become his home. Not anti-American, he still displays remarkable perspicacity about the problems, and delineates differences from European approaches. His reports are not ideologized, but are written from a wide perspective, avoiding simplistc judgements. Comments about how the US responds to events in the Soviet Union and the Eastern bloc cast a persistently relevant light on Cold War issues. At one point, he’s reprimanded for reflecting on presidential election issues in November 1948, and for offering excessive, wide-ranging opinions – he’s told he should restrain himself to cultural issues. Yet he was also evaluated as an effective, knowlegeable employee.

The edition concludes with afterword by Marek Kornat, who explains the biographical and political context of Miłosz’s life in the US. An index of names provides an effective tool for general readers and for researchers.

Author: Klementyna Suchanow