Christmas ended the period of fasting, silence, and reflection, and began the time of joy that followed the birth of Christ. The atmosphere of Christmas, its traditions and customs, family meetings, and common carol-singing filled almost every old Polish manor house. Many Christian homes also celebrated All Souls’ Day and observed New Year’s ceremonies, which were still rooted in pagan customs. In Old Poland, as Christianity was introduced to Polish lands, Christian traditions often clashed with various non-Christian customs.

by Anna Wójciuk

Advent – waiting for the birth of Christ

In Old Polish times, Advent lasted forty days. It was the period that preceded the nativity of Christ and included the preparation for Christmas. All farm work had to be completed by the first day of Advent. After that, it was time for rest and silence. Loud parties ceased, and music fell silent. Neighbors, friends, and families participated in the rorate, i.e. the mass in honor of the Mother of God. According to Christian tradition, candles symbolizing Jesus, i.e. the light brought by Mary, were lit during the service. In old Poland, during the rorate mass, there was a ceremony of lighting seven candles with the king’s participation. The ruler would say, “I am ready for God’s judgment, ” and place the first candle on the highest candlestick on the altar. The clergyman placed the second candle, the secular senator the third, the landowner the fourth, the knight the fifth, the burgher the sixth, and the peasant the last candle. Everyone, in turn, repeated the words spoken by the king.

Folk customs often added another symbolic element to Advent celebrations, while some practices related to the gospel, others were associated with agricultural traditions. The weather was carefully observed, as it was believed that the weather on Advent days determined that of following months. Advent wreaths had a symbolic character. Made by hand from mistletoe, yew, or holly branches, a wreath hung on the door of a house or manor was supposed to protect against evil forces. Advent ended on 24 December.

Christmas Eve

Christmas Eve began on 24 December. Particular attention was paid to the symbolism of numbers. There is a common belief that there should be an even number of people at the Christmas Eve dinner. Breaking with this tradition heralded misfortune and foreshadowed the imminent death of one of the household members or one of the guests. The symbolism of numbers also referred to Christmas Eve dishes: an odd number of dishes were prepared. In this way, the magnates ate eleven dishes, nine appeared on the tables of the nobles, and seven in peasant houses.

On Christmas Eve, they predicted the future – a joyful Christmas Eve heralded the household’s prosperity in the coming year. A girl grating poppy seeds for the Christmas Eve dinner would marry soon, and a successful hunt heralded good luck in the future. On Christmas Eve, there was no need to argue and fight. All quarrels, fights, and loans heralded misfortune. It was also forbidden to borrow anything.

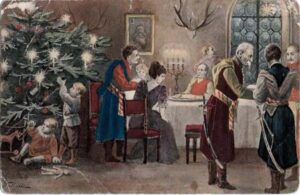

Houses were decorated for the Christmas Eve dinner. It is worth remembering that the custom of decorating a Christmas tree was not known in Old Polish times. The custom was adopted from the Germans at the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th. Decorative fir branches were hung on the walls, ceiling, door, or fence. The ornamental green branches symbolized life, love, family ties, happiness, health, vitality, and a successful harvest. In memory of the stable in Bethlehem, a hay was spread on the floor and under a white tablecloth. In some houses, a sheaf of grain was placed in the corner of the room where the Christmas Eve dinner was served.

On Christmas Eve, the duty of men was to hunt and fish. The sumptuousness of the festive table depended on the success of the hunt. In addition, it was believed that a plentiful catch and a large amount of prey was a very good omen, foretelling happiness in the new year.

Meanwhile, the host’s wife and other women prepared a Christmas Eve dinner consisting of many dishes. The lavish, but at the same time, light fasting dishes of the Christmas Eve dinner would ensure abundance and prosperity in the following year. Old Polish Christmas Eve dishes include borscht with dumplings and mushrooms, hemp seed soup, almond soup with raisins, mushroom soup, fish soup, various types of fish, kutia, Lenten dumplings, soup made of prunes, pears or apples, cabbage with peas or beans, dumplings with poppy seeds, honey or sugar, dried or cooked turnip, oat jelly, honey gingerbread, strudel, and wheat cake.

After the house was properly decorated and the food prepared, people looked at the sky. When the first star appeared, the Christmas Eve dinner was attended by all household members, both hosts, and guests, as well as servants. In the spirit of love, brotherhood, respect, peace, and unity, a wafer was broken that was believed to possess extraordinary power. The Old Polish community believed that the custom of sharing this wafer provided God’s protection and sincere wishes would soon come true.

After making wishes, a prayer was said together, and the Christmas Eve dinner was enjoyed. According to the old Polish tradition, every dish had to be eaten or tasted. It was an expression of respect for the land yielding crops and protecting against hunger. Moreover, to avoid poverty, illness, and death, everyone was expected to sit at the Christmas Eve dinner table. Therefore, only after eating all the dishes could one leave the table. It is also worth remembering that during the dinner, everyone was in a solemn mood. The past year was discussed, faith and family history were spoken of, deceased relatives, and friends were remembered and religious songs, carols, and pastorals were sung.

In Old Polish times, some of the most beautiful and popular Christmas carols were translated or written in Polish. The authors of the texts were great Polish preachers, moralists, writers, and poets: Piotr Skarga, Hieronim Morsztyn, Wespazjan Kochowski, and Franciszek Karpiński.

On the night before Christmas, special attention was paid to the dead. An empty place was left at the festive table to honor their memory, remaining there for the whole night in some mansions and houses. It was a gift for the spirits of dead relatives who, according to old Polish beliefs, returned on Christmas Eve and visited their loved ones by the grace of God. Speaking of gifts, it is worth remembering that gifts were given in very few homes during Christmas. In Old Poland, gifts were usually given on New Year’s Day. These were usually: dried fruit, gingerbread, cookies, and candies. Children were most often given school supplies or shoes. On Christmas Eve, animals were also remembered and given the leftovers of a gala dinner. It was believed that those gifted with Christmas dishes would have good health, which would benefit the hosts, i.e. dogs would guard the manor or house better, hens would lay more eggs, and cows would give more milk. Wild animals were also remembered, especially wolves. The dinner leftovers lured them as close to the homes as possible. This practice was related to other folk beliefs. It was believed that a wolf invited to Christmas Eve will not approach the house in the following year, which would protect farm animals.

After the Christmas Eve dinner, all the faithful went to Midnight Mass. Participation in this nightly service in honor of the birth of Jesus was a Christian duty. No one was excused. People who could not stay up until midnight and had fallen asleep were woken. For refreshment and health, the face and feet were washed. The most resistant to winter cold and frost bathed in the open air, it was supposed to bring good health in the new year.

The men willingly took part in a carriage and wagon race on the way to the church. It was, of course, symbolic. It was believed that the farmer who entered the church first would have the best harvest. On the way back, the men raced again. People who did not participate in the race slowly returned home, singing hymns, carols, and pastorals. The sky was also closely watched. According to old Polish beliefs, a cloudless and starry sky heralded a good harvest, a foggy one boded a humid year full of pests, and the clearly visible milky way ensured plenty of milk and forests full of fruits and mushrooms.

Christmas Day – December 25

On Christmas Day, the faithful participated in the holy mass, during which carols and pastorals were sung. The clergy preached joyful sermons, often of a humorous nature. In this way, the joy of the birth of Christ was emphasized. After the service, people returned home and celebrated lavishly. Guests were treated primarily to meat dishes and sweets. Fasting was over, one could eat everything without much restriction.

Christmas was spent mostly at the table. It is generally accepted that no farm work was done on this day except for the necessary care of animals. It was forbidden to clean, chop wood or fetch water from the well. All these duties had to be done before Christmas. Breaking this custom revealed the person’s unworthy character and threatened failure in the coming year. Besides, it was a sign of vanity and a bad upbringing to look at yourself in the mirror and to frequently fix your hair. The day of Christ’s birth was to be spent piously and cheerfully.

Saint Stephen’s Day – December 26

On the second day of Christmas, the ceremony of blessing cereal grains took place in churches. During the mass, the faithful showered grain on themselves, the priest, and the clergyman. The martyrdom of Saint Stephen was commemorated in this way. This gesture was also supposed to ensure prosperity and fertility in the new year. The clergy began visiting the faithful. For the blessing of manors and houses, they received cash donations and homemade food products, such as cheese and mushroom dishes. Farmers, students, and city servants also came to manors and cottages. They were carol singers with specially prepared humorous performances, songs, melodies, and wishes for household members. The Old Polish community willingly hosted them because they introduced a cheerful mood, for which they received various gifts.

Saint Stephen’s Day was also a day of mating and courtship. The bachelors who wanted to marry visited the girls they liked. Women were usually happy to be visited because spinsterhood in former Poland was badly perceived. Therefore, men were eagerly awaited in the houses of unmarried ladies. In short, Saint Stephen’s Day was a day of engagement expectations.

It is worth remembering that in old Polish times, Christmas did not end on 26 December. It lasted until the Epiphany, a Christian celebration in honor of the revelation of God to man. Almost every holiday day, guests were received, social meetings were organized with various entertainments, carols and pastorals were sung together. Nobody worked, and everybody rested. Efforts were made to joyfully celebrate the birth of Jesus.

Author: Dr Anna Wójciuk

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin