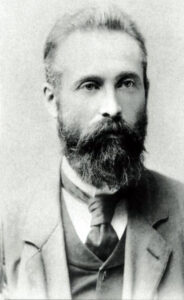

Bronisław Piłsudski was the older brother of Józef Piłsudski, one of the leaders responsible for bringing about Poland’s return to independence in 1918 after more than one hundred and twenty years of partitions. Józef’s decision to become involved in the independence movement was largely influenced by the fate of Bronisław, who participated in an anti-tsarist conspiracy. In 1887, Bronisław was sentenced to several years of exile in faraway Sakhalin. While there, he conducted ethnographic studies on the peoples of the Far East, particularly the Ainu.

by Piotr Bejrowski

Bronisław was born in 1866 in Zułów in the Vilnius Region and was one of the sons of Józef Wincenty Piłsudski, a participant in the January Uprising in 1863, and Maria née Billewicz. He was a year older than his famous brother, Józef. At the age of twenty, he was admitted to the Law Faculty of St. Petersburg University where he became close to a radical revolutionary organization called Wola Ludu. In 1887, he became involved in preparations for an attempt on the life of Tsar Alexander III. Notably, this band of terrorists also included the elder brother of Vladimir Lenin, Alexander Ulianov.

In the end the action did not take place but the participants were exposed and several death sentences were handed down after a five-day trial. Bronisław was also sentenced to death, but eventually the sentence was commuted to fifteen years of hard labor in the Far East. Bronisław later admitted to regretting his participation in the plot and admitted that he was an opponent of violence, and considered participation in any terrorist actions as contrary to his character.

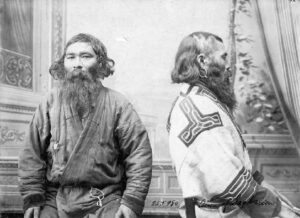

Knowing the realities of exile well, he feared being forced into hard labor. However, when he arrived at the island of Sakhalin, local officials employed him as an office worker and as a teacher. It was there that he came into contact with the life of local peoples – the Ainu, Nivkha, Mangun and Orok. This interest quickly turned into a fascination with the indigeneous cultures and languages. Like dozens of other Polish exiles unable to return to their homes, Bronisław undertook work that would contribute significantly to the discovery of so far unexplored lands for science.

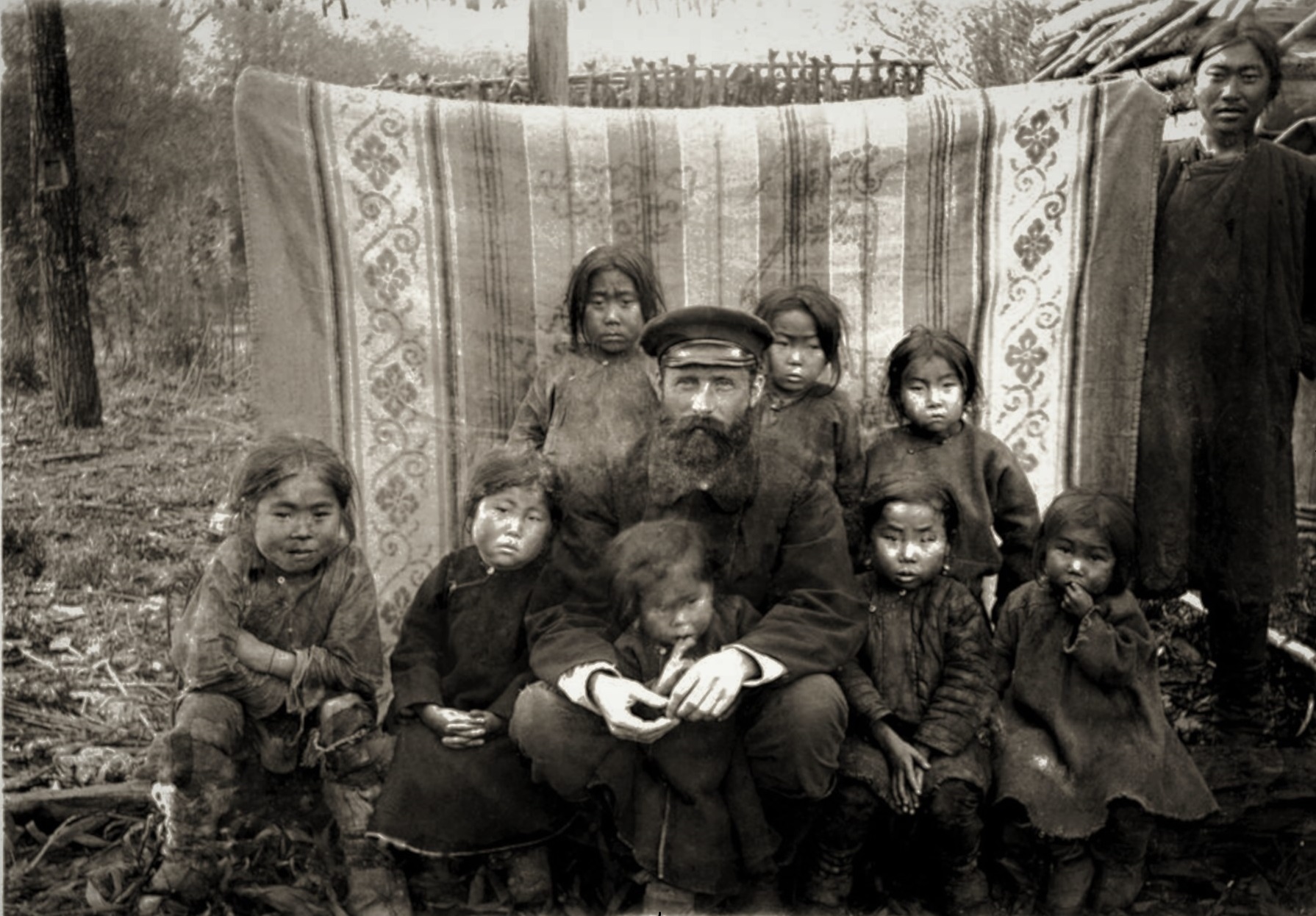

The local peoples, however, were illiterate, so Piłsudski undertook to study their spoken languages with great dedication. Together with the writer Wacław Sieroszewski, also an exile, he made unique recordings of Ainu speech and chants on wax cylinders. Several decades later, the Japanese company Sony would manage to restore these recordings. As a result of his research, during which he wrote down and translated several thousand words in Ainu, Gilack, Orocki and Manga, several dictionaries were produced. His work also contains exhaustive descriptions of the customs of these peoples and their religions, as well as local legends, stories, fairy tales, and songs. Bronisław also took several hundred photographs of the communities he studied. He also founded several schools, and wanted to codify local regulations and the development of rules of administration. It is also worth noting that in addition to his research, Piłsudski repeatedly petitioned for an improvement in the fate of the Ainu through official channels.

The Ainu and Nivkhs welcomed him with great affection and treated him as a member of the community. He even married an Ainu girl and had two children with her – a son and a daughter. The enormous merits of Bronisław Piłsudski came to the attention of the local authorities, and they managed to win an amnesty for the Polish ethnologist. He continued conducting his research up until the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese war. Then in 1905, he finally left Sakhalin, although his wife and children remained behind because the Ainu people forbade women from leaving the village. However, Bronisław missed his homeland and in the end, left without the consent of the Russian authorities.

He travelled to Hokkaido and then to the United States, and eventually reached Poland, although it was still under partition. Using his ethnologist experience, he began researching the inhabitants of Podhale. He aspired to academic work, but had no formal education (he was only a freshman when the plot on the tsar was revealed). He performed odd jobs to earn a living while conducting his research. The exhibits collected by him are still on display at the Tatra Museum in Zakopane. His efforts were finally appreciated – the Krakow Academy of Science awarded him a salary. However, he did not enjoy it for long, the First World War soon broke out, and when news came about Russian troops approaching Galicia, he decided to depart for Austria, Switzerland, and then France.

When he came to Paris, he again felt the loneliness and alienation of the eternal wanderer. He became involved in independence activities, but did not understand the disputes between Polish emigrants. He was diagnosed with depression, and his feelings of alienation and instability likely exacerbated his symptoms. In May 1918, just a few months before the end of the war and Poland’s regaining independence, he was discovered drowned in the Seine. He was fifty-one years old. Paris police had no doubts as to the cause – suicide caused by deepening depression.

History was not kind to the Ainu. They endured oppression by Japanese authorities but the years under Soviet rule brought about the greatest damage. Bronisław Piłsudski made a great contribution to the preservation of this Far Eastern culture. To this day, there are tens of thousands of Ainu on the island of Hokkaido, of whom only a small part speak the Ainu language. The descendants of Piłsudski still live in Japan – they are the only still living descendants in the male line of this distinguished family from Zułów.

Author: Piotr Bejrowski

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin