People wrongly believe that as of 11 am on 11 November 1918 the ceasefire was called and peace restored. This was not the case in Central and Eastern Europe where one must instead speak of ongoing hostilities and violence, says Bartosz Dziewanowski-Stefańczyk from the European Network Remembrance and Solidarity. Why the years 1918-1923 were times of great ambiguity? How to deal with the Gordian knot of Central European memory? Read the whole interview!

polishhistory: The well-known German political scientist Jan-Werner Müller has stated that, as a result of the First World War, the world dissolved into a ‘Molten Mass’. This was a drastic shift away from the 19th Century, once labeled the ‘Golden Age of Security’ in Stefan Zweig’s writings. Could we call the period covered by the exhibition ‘After the Great War. A New Europe 1918-1923’, a time for the ‘congealing’ of this ‘Molten Mass’?

Bartosz Dziewanowski-Stefańczyk: Given the scale of social, political and economic changes in Europe and in other parts of the world at the end of the First World War, we could say that society was indeed a ‘Molten Mass’ in many places. Borders were shifting, as can be clearly seen in maps of the time. In atlases, textbooks and monographs, the marking of the borders made in 1914 and in 1923, i.e. the periods before the changes, or shortly after settling them, is most often shown. It is difficult to adequately represent a transitional period when certain territories are in the process of changing their affiliation as a result of wars, uprisings, plebiscites and treaties. These changes were taking place on a global scale – the war was called a world war for a reason. It is also worth pointing out the influence of the idea of self-determination of nations, promoted by the President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, on the emergence of anti-colonial movements in various parts of the world – including Egypt, India, Korea and Vietnam. The mandate system introduced by the League of Nations was essentially a death knell for colonial empires. So perhaps even more accurate than Müller’s thesis was the statement made by the Canadian historian Barbara Macmillan: ‘In the fluid world of 1919, it was possible to dream of great change, or have nightmares about the collapse of order’. These were times of great ambiguity.

However, the outlook was different. Changes looked different in the centre than in the periphery…

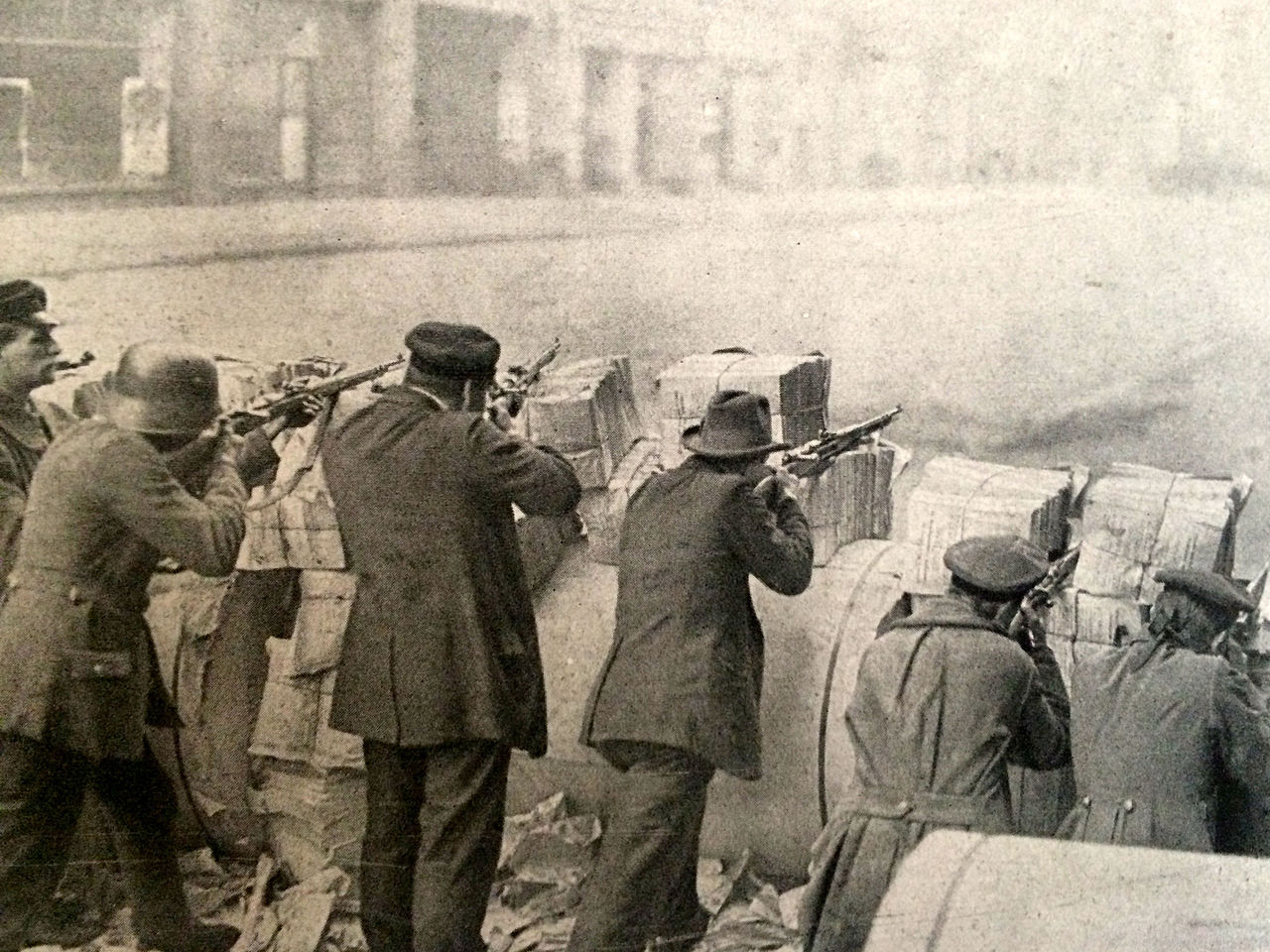

The notion of the ‘cooling’ of the ‘Molten Mass’ comes from a solely Western perspective, misconceptions persist about what happened on 11 November 1918. People wrongly believe that as of 11 am the ceasefire was called and peace restored. This was not the case in Central and Eastern Europe where one must instead speak of ongoing hostilities and violence. This perspective is more and more often accepted by researchers – most recently by Włodzimierz Borodziej and Maciej Górny, Robert Gerwarth, Jörn Leonhardt and Jay Winter. It also influenced our thinking when we undertook to create an exhibition that would reflect the turbulent birth of a new order in this region. In 1918-1923, a large part of the area between Germany, Russia, Finland, Greece, and Turkey (including these countries) was in a state of war. Therefore, the ‘cooling’ of this ‘Molten Mass’ was a lengthy process. Meanwhile, further peace treaties were still being signed – in Riga in 1921 between Poland, Soviet Russia and Ukraine, and in Lausanne between Greece and Turkey in 1923. 1921 was also the year of the last Silesian Uprising.

But we are talking not only about armed conflicts.

Definitely. The years 1922-1924 include a period of hyperinflation in Austria, Germany, Poland and Hungary. The latter was recovering after the Béla Kun revolution and was undergoing the White Terror. Meanwhile in Soviet Russia, in conjunction with the Red Terror, socio-economic experiments were being implemented and a completely new state was being created. The countries of the region also had to re-integrate societies which now consisted of a large percentage of national minorities – partly due to the already existing multicultural characteristic of the region and partly as a result of migration and border changes. Even though the foundations of new statehood came into being after 1918, I think that the ‘cooling down’ only truly began after 1923, when borders were set and economic reconstruction finally began to repair the damages caused by war and inflation.

A lot happened during 1918-1923, from your perspective, as one of two curators of the exhibition, what was most important?

Instead of presenting one topic in detail, we decided to keep our focus wide. What’s more, we tried to cover a vast geographical area — the whole region of Central and Eastern Europe (the so-called New Europe). We also tried to present as many perspectives as we could, as is consistent with the approach of the European Network Remembrance and Solidarity (ENRS), the institution which created the exhibition. With these exhibitions – but also with conferences, books and seminars – ENRS is trying to create a platform for dialogue that will facilitate communication between European societies.

In many countries, the experience of this period remains vivid and affects both national memory and prevailing attitudes towards neighbouring countries.

That is why getting to know different perspectives is so important. Therefore, visitors will learn not only about the revolution in Russia, but also the ones in Hungary and Germany. We emphasize that the creation of new states with – at least initially democratic systems – can be in a sense called a revolution. We are talking about the Paris Peace Conference and the attempts to create a new order by the leaders of the victorious Entente and a selectively introduced principle of self-determination. The creation of a new order in the region, however, was not a process that was manually imposed from Paris, as border conflicts and civil wars created a new political landscape, and left behind so many victims that it led to further waves of migration. It is particularly important to indicate different points of view in the provisions of peace treaties, plebiscite results and, as a result, the new borders. After all, what was successful for some – e.g. the incorporation of Transylvania into Romania, the incorporation of Vilnius into Poland, and the division of Belarus between Poland and Soviet Russia – often meant a painful, sometimes traumatic defeat for the other side.

Is that why the exhibition doesn’t only talk about politics?

Naturally, that’s why we also present other topics, such as economics, art and culture, and social history. We are talking about the victims of war – not only about soldiers, but also about widows, orphans and disabled persons for whom the war basically never ended. We talk about the victims of the Spanish flu, who amounted to more than the victims of direct warfare altogether, but whom nobody remembers today. We also show the difficult situation of the area’s Jewish population both during and shortly after the war – there were over one hundred thousand victims of pogroms in Central and Eastern Europe who have since been forgotten.

Finally, we also show the first post-war years as a period of great transformation. We offer examples of attempts to regenerate and develop art as part of dadaism or primitivism and by using new techniques such as collage or film. Visitors will also find examples of new trends in architecture – e.g. Bauhaus glass houses, constructivist and avant-garde designs from Russia, and an unrealized Paris reconstruction plan by Le Corbusier. In these years, the unprecedented liberation of women – both professional and political – occurred in our region when they entered labour market and received electoral rights. Such positive examples of change in various spheres of life, taking place in parallel with the problems mentioned earlier, are of course numerous, and only confirm the opinion of Macmillan which I mentioned earlier.

The exhibition also has elements related strictly to memory.

In addition to traditional monuments, we exhibit anti-war art and examples of propaganda posters, mainly from plebiscites and war periods. A separate part is devoted to the propaganda of the new authorities in the region. We discuss the founding fathers of new nations, who were often victorious military commanders from the First World War. The variety of media through which these characters were promoted at the time was unusual, and included things such as postcards, monuments, banknotes, medals and children’s magazines. At the same time, we also reflect on the problematic aspects associated with them – most of them turned out to be authoritarian rulers.

There is also a part of the exhibition presenting contemporary memories of those events. We asked authors to prepare a brief presentation of what has remained from the collective memory of their societies at that time. We grouped the memories into those of success (e.g. Poland and Romania), failure (Bulgaria and Hungary), as well as mixed memories (e.g. Lithuania and Germany) and the recollection of a short period of own statehood (Belarus and Ukraine). Additionally, every time the exhibition moves to a new country, we also present the memory in that country. In Autumn 2018, the exhibition opened in Prague and then in Sarajevo, while in 2019 it visited Bratislava, Verdun, Berlin and Weimar and each time we also presented the collective memory of the mentioned period in those countries.

From the point of view of a modern Central European resident, the term ‘New Europe’ is not obvious. Where did the idea for this exhibition title come from?

This term is not obvious, but also the story we tell is not well known. It is not only Western societies who do not know the history of Central and Eastern Europe – even here we lack knowledge. Most often the story functions within the framework of national history, as a consequence of which the stories of national minorities or neighboring countries are poorly known.

The term ‘New Europe’ comes from Czechoslovak President Tomasz G. Masaryk, who first published a magazine under this title during the war, and then published a book in which he described the new political order in the region he called ‘New Europe’. Therefore, this term should not be confused with the new member states of NATO or the European Union. On the other hand, the fact that a large part of the countries that were created in 1918 entered the EU in 2004 – and many borders still coincide with those from a hundred years ago – seems to be proof of the long-term changes that began after the Great War.

These six years are not only an example of an exceptional ‘concentration of time’. How can a modern historian pick apart the tangle of myths, strongly supported by the historical policies of nation-states, to better understand the events of that period?

Foundation myths, creating new symbols, worshiping some heroes and forgetting about others is a natural and timeless phenomenon. What’s more, it becomes double-barreled after every moment of breakthrough when new authorities assume the mantle of legitimacy. In this regard, it is not surprising that after 1918, in the new countries, it was mainly soldiers that were mentioned, not those who died serving in the former imperial armies. The creation of new symbols in each of the countries was also accompanied by the destruction of those from the former powers. Hence, for example, the destruction of the great orthodox church on Saski Square in Warsaw in the mid-1920s was not an isolated case in the region. Similarly, although the Polish-Bolshevik war was one of the largest conflicts and of exceptional significance for Europe, it should not be forgotten that, in principle, all the countries of the region also remember their wars with the Red Army. How memory is created is also evidenced by the fact that in nearly every victorious state of the region, one can point out several possible dates for the beginning of statehood. The final choice for each date of the national holiday was simply arbitrarily made by those in power at the time.

Does this mean that it was a heroic period for all Central European countries that were emerging or regaining independence?

Certainly not for all of them. Countries that were not satisfied with the new order introduced a policy of revisionism, pursuing a fundamentally different historical policy. Moreover, it is worth emphasizing that the myths and official memory that were popularized and promulgated changed depending on the political power. Lengthy disputes about which day should be chosen for Independence Day serve as a testimony to this process in Poland. A clear change also concerned the nationalistic narrative, initially propagated by National Democracy. In the second half of the 1920s, after the takeover of power by Józef Piłsudski, it was replaced by a more inclusive, pro-state narration.

So how do you deal with the Gordian knot of Central European memory?

First of all, a historian should conduct comparative studies: often what is considered unique for a given country, may, in practice, be a phenomenon on a much broader scale. Secondly, there is a constant need to remember all the different people involved in history-making and their divergent perspectives – not only the majority groups and narratives but also the minorities and their experience.To untie this knot, one needs to know not only facts, but also be familiar with studies devoted to memory culture and historical politics. All of this should raise everyone’s awareness – not only that of professional historians that many narratives which we take for granted result from an arbitrary idea of a given country. Such knowledge should also be an important element of civic education, as highlighting certain topics causes others to be forgotten. That is why I think that we should talk more about the situation of national minorities and other social groups after 1918, and thus about different perspectives and memories – not only the official ones.

The exhibition ‘After the Great War’ is traveling all over Europe. What do you consider its greatest value?

Definitely the greatest value is the presentation of the period, the importance of which is too often forgotten, from a regional perspective, as neither we nor the West know so much about. We have invited over 40 historians from over 20 countries to work on the exhibition. By the way, international cooperation is also one way out of the rigid framework of particular historical though trends. The exhibition team cooperated with researchers from the West, as well as from most of the countries we are talking about. As a result, Central and Eastern Europe has been given the opportunity to talk about itself using other research perspectives.

Does the exhibition evoke reactions that the creators did not expect?

Regardless of previous studies, we better understand that the problems we talk about are still vital. Of course, there were disputes among the authors of the exhibition, and on a closer look we understood we are dealing with quite contemporary problems. Migration and attempts to integrate new societies, the creation of historical policies by newly created states, or the susceptibility of societies to authoritarian governments in response to an uncertain political and economic situation all got their start in the 1920s.

Where can the exhibition be seen in the coming months?

In 2020, we plan to present it in Turin, Rijeka, Vilnius, Riga, Tallinn, Warsaw and Bucharest. The project will last until 2023. In practice, we treat every opening as if it was the first one, because in each country there are two language versions – English and local, which requires constant work on translations and editing. In each country we have a fragment dedicated to memory in that country, which in turn means continuous cooperation with researchers. In addition, we always try to organize accompanying events – tours, workshops for students or teachers, discussions and conferences. I warmly invite you to read the catalogue and visit our exhibition!

ENRS: European Network Remembrance and Solidarity (ENRS) is an international undertaking aimed at the study, documentation and dissemination of knowledge on the history of 20th Century Europe with particular consideration for periods of dictatorship, war and social upheaval in the face of oppression. Network members are: Germany, Poland, Slovakia, Hungary and Romania. Albania, Austria, the Czech Republic, and Georgia have observer status. More: www.enrs.eu

Exhibition: The outdoor traveling exhibition ‘After the Great War. A New Europe 1918–1923’ focuses on the turbulent first years after the First World War. Over 200 archive and multimedia materials – pictures, maps and original films from the 1920s, together with the individual stories of people who lived through these times, present a complex yet coherent picture of the New Europe established in the east-central part of the European continent. The main goal of the project is to illustrate the scale of political changes and show its impact on current politics as well as to present different national memories. The exhibition takes the form of a white and silver pavilion in the shape of a cube. More: https://enrs.eu/afterthegreatwar

Bartosz Dziewanowski-Stefańczyk, PhD – researcher and deputy head of the Academic Department at the European Network Remembrance and Solidarity (ENRS). He received his PhD degree (2013) from the History Institute of Warsaw University. Dziewanowski-Stefańczyk worked for the Center for Historical Research of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Berlin (2012-2015), was scientific secretary of the Polish-German Textbook Commission (2012-2016) and worked as a secretary of the Polish-German History Textbook. Together with Dr. Robert Żurek, he is curator of the exhibition ‘After the Great War. A New Europe 1918-1923’ and is conducting research on Polish politics of history in the 20th Century. He specializes in Polish-German relations, cultural diplomacy, the politics of history and monetary history.

Interviewer: Michał Przeperski

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jesica Sirotin