In his actions and writings, Adam Jerzy Czartoryski combined the ethics of the Enlightenment with a romantic vision of the world. From St. Petersburg and Paris he pursued a European policy, and in his book Rozważania o dyplomacji (Reflections on Diplomacy, 1830) he presented and developed the idea of a united continent ‘A Europe of nations’. What was the life and career of a man who, in exile, was de facto minister of foreign affairs of a non-existent state?

by Piotr Bejrowski

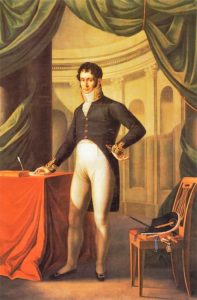

On 14 January 1770, Adam Jerzy Czartoryski, one of the greatest Polish diplomats and political thinkers of the 19th Century, was born in Warsaw. Early in his career, he was a friend and adviser to Tsar Alexander I for several years, and was one of the most influential politicians in Europe. Then – disappointed with Russia – he shifted his focus and emigrated to France, where he headed the conservative group known as ‘Hotel Lambert’.

In the early 1760s, the Czartoryski family saw the actions of Tsarina Catherine II (1762-1796) as a chance to overcome the crisis the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had succumbed to, hoping limited political reforms would save the situation. Some continued to believe, although the situation was completely changed after the third partition of Poland (1795), that it would be advantageous to resurrect the Polish-Lithuanian state in a dynastic union with Russia. This was a very important concept in Czartoryski’s thinking and writing, that had long appealed to Adam Czartoryski’s political thinking.

However, before Adam Czartosryski joined the Russian service as the representative of a powerful noble family, he visited several Western countries, including England, Germany and France, was a member of the Great Sejm (parliament) and took part in the Polish-Russian war in defense of the Constitution of 3 May 1791, thanks to which he was awarded Poland’s highest award, the Order of Virtuti Militari.

In 1796, Czartoryski became close to Grand Duke Alexander, who five years later ascended the Russian throne as Tsar Alexander I. The latter was supposed to assure his friend of his sympathy for the Polish cause and the need to change the rules governing Russian policy. In 1801-1806, thanks to his aptitude and support of the tsar, Czartoryski was his closest adviser. He headed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Wileński Okręg Oświatowy (the Vilnius School District) and the renovated university in Vilnius, he was also a member of the Council of State and a senator.

While most compatriots hoped Poland would regain sovereignty with the help of Napoleon, Adam Czartoryski, in the service of Russia, persistently built subsequent anti-French coalitions and argued for basing the European order on an agreement between St. Petersburg and London. Czartoryski was the author of the so-called Puławy Plan (Puławski Plan), the concept of Poland’s revival under Alexander’s rule, including the lands taken from Prussia. By presenting the tsar with the manifesto O systemie politycznym, który winna stosować Rosja (The Political System that Russia Should Apply), Czartoryski probably had high hopes for a change in the policy of the Russian Empire. He believed liberal solutions were possible, as he believed in Europe and an enlightened Russia.

Tsar Alexander did not turn out to be the saviour of Poland. Czartoryski did not understand for a long time that a country’s internal system determines foreign policy, and rid eventually himself of these illusions after Nicholas I ascended the throne in 1825. However, before this happened, Adam Czartoryski returned to the great diplomatic game during the Congress of Vienna. According to the eminent Polish historian Szymon Askenazy, Czartoryski, contributing to the creation of the Kingdom of Poland and confounding the partition of Poland, obtained in 1815 exactly as much as he was able. He prepared the principles of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Poland and became a member of the government. At the same time, he gradually became distant and drifted away from his former friend and the Romanov family as a whole.

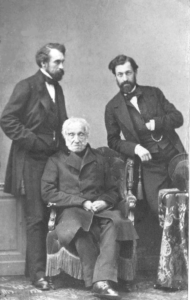

When an anti-Russian uprising broke out in Warsaw in November 1830, Czartoryski joined in to lead the National Government. After the uprising was suppressed, he settled permanently in Paris, where he established the Polish political centre. He headed the conservative group called, from the place he lived in, the ‘Hotel Lambert’, and tirelessly raised the issues of his homeland on the international arena. As an active diplomat, he was involved in, among others, the Revolutions of 1848, the Hungarian Uprising and the Crimean War. He was in favour of the liquidation of serfdom in the Russian partition and advised signing an agreement with the Austrian government. Czartoryski’s activity was impressive and had extremely significant symbolic significance. In the political sphere, however, it did not bring results. Adam Czartoryski, the eminent politician, died 15 July 1861 at the age of ninety-one. In his will, he challenged the Polish diaspora to serve Poland.

The outstanding Polish historian Jerzy Skowronek, the biographer of Adam Czartoryski, called him a ‘politician of defeat’. However, this opinion is exaggerated. Undoubtedly, Czartoryski lost the fight, but his ideas became real over the long run. Historian and writer Jerzy W. Borejsza, called Czartoryski “a great figure of Polish and European policy.” Indeed, he was a patriot, statesman and distinguished international politician. In his writings, he criticized the ‘sacred covenant’ and insisted on reforming the rules governing relations between nations. In his view, human rights and the rights of nations should always go together. He was in favour of a parliamentary system and a ‘Europe of nations’ – a united federation of states that would ensure a balance of power.

Author: Piotr Bejrowski

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin