During his life and also after his death, Piotr Skarga divided the opinions of Poles. For some he was “the main troublemaker of the Republic of Poland,” and for others he was a prophet of “the misery after the partitions,” who by all means tried to save the sinking ship – Poland.

by Jan Hlebowicz

According to some sources, Skarga [whose surname means “complaint” in Polish] owed his surname to his grandfather – Jan Powęski, who repeatedly sued others for things. Piotr was born in 1536 in Grójec in Mazovia to a noble family. He was the youngest of six children. “From his family home he brought out a strong faith, piety and deep attachment to the Catholic faith. Anyway, the entire district of Mazovia was the mainstay of Catholicism. Religious news did not find an audience here, and there were only a handful of supporters of the Reformation,” wrote Marek Balon, biographer of the clergyman.

He was all on fire as he climbed onto the pulpit

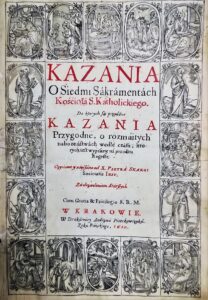

The complaint was shaped ideologically after his stay in Rome, where he began his novitiate in the Jesuit Order. “His superiors saw in him excellent health, a talent for preaching, a gift of speech, and the ability to hear confessions,” enumerated Prof. Janusz Tazbir. After two years, he returned to Poland and took up the position of lecturer and preacher at the Jesuit college in Pułtusk. Then he was moved to Vilnius, where, inter alia, he was the rector of the local monastic college. At that time, he developed a wide range of activities: pastoral, pedagogical and literary. He was an excellent polemicist who “devoted his literary talent to the service of the Church.” Skarga called for the restriction of privileges for Protestants, hence he was called a counter-reformation swordsman. He left behind trials against Calvinists, including “Pro Sacratissima Eucharistia” and a work calling for the unity of the Roman Catholic Church with the Orthodox Church.

The Jesuit’s Lives of the Saints brought him great fame – a real bestseller of old Polish literature, where ancient legends were adjacent to stories about outstanding contemporaries. The result of Skarga’s zealous preaching activity in Vilnius was, among others, the adoption of Catholicism by the Deputy Chancellor of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Lew Sapieha.

Appreciating the successes of the clergyman, King Stefan Batory of the Jesuit College in Vilnius established the Academy, and Skarga became its first rector. The Jesuit proved to be an outstanding orator. According to Prof. Kazimierz Panuś, his rhetorical style [was unique.] “He was by nature an energetic, lively personality (…). Immediately after entering the pulpit, he was all on fire, thundered like a thunderstorm, dazzled like lightning. Sometimes he asked and begged, prayed and fell on his face before the Lord, only to hurl spells and threats in a moment, taken down by indignation. He had the innate quality of the greatest speakers: the power of inspiration and the gift of kidnapping people’s hearts.” “He was a passionate Masurian, he often spoke before he thought. Piotr Skarga would probably be a journalist today,” said Prof. Tazbir. However, “other features, namely a lack of social tact, uncompromising and radicalism, as well as progressiveness, were the cause of much aversion to him, or even hostility,” indicated Prof. Andrzej Bruździński.

The time of divine vengeance will come upon you!

The fight against the Reformation, a strong central government in an absolutist spirit, limiting the role of the Sejm to an advisory body and depriving the nobility of some privileges – these were the main postulates of the rich political writings of the Jesuit. In his famous “Sejm Sermons,” Skarga criticized the tendency to “tolerate heresy and love anarchy,” which, in his opinion, resulted from the misunderstanding of the word “freedom” by the nobility. The Jesuit also lamented the weakness and cowardice of the nobility. He called for penance, but at the same time announced that the Poles would be reached by divine justice. He wrote, “The time of God will come and the time of divine vengeance upon you. And it was so. Grow in sins, sad people, until you grow old in them. Pour on the barrels of God’s wrath until you break open. Oh, alas, for your folly!”

The period of the Jesuit’s greatest political activity fell during the reign of Sigismund III Vasa, whose politics, both in the external and internal dimension, were not positively assessed by a large part of the Polish nobility. As the opponents of the monarch pointed out, Sigismund III cared more about the Swedish crown than the Polish one, and achieving this goal often ran counter to the interests and good of the Republic of Poland. The ruler was also a staunch supporter of the Counter-Reformation and strove to “force the country into the scheme of the political system implemented in the Habsburg states.” Known for his passionate sermons and determined political views,Skarga was asked by the monarch at the end of January 1588 to assume the function of a court preacher. “The king is always at a Polish sermon by Skarga, a Jesuit (…), or someone else he sends in his place sometimes when he has an obstacle, although it rarely happens,” wrote Bishop Claudio Rangoni, nuncio to the Holy See.

The evil spirit and the main troublemaker?

Skarga was neither afraid to admonish the king, nor to give advice and guidance to the young monarch. However, he did not take advantage of his strong position at court in the ongoing political game. He clearly addressed people seeking protection from Sigismund III through him: “Do not come to us for vacancies and ask for your benefits; you have offices and chancellery, secretaries – come to us for confession and for spiritual advice.”

Despite this, as one of the ruler’s closest advisers, he was called by his opponents “the main troublemaker of the Republic” and “the evil spirit of the king.” For a large part of the nobility, he became enemy number one, and the accusation painting the Jesuit as a symbol of religious fanaticism with “bloody ambitions” gained considerable popularity in the following centuries. On the other hand , he was considered a “saintly man” who always “wanted to be faithful to God, the Church and the Fatherland” by his supporters. Skarga, in essence, tried to apply [in real life] what he preached from the pulpit.

He conducted wide-ranging social activities, establishing new types of charitable institutions. The goal of the Brotherhood of Mercy was “to come to the aid of people incapable of independent existence.” In turn, the box of St. Nicholas was a kind of dowry fund for poor brides getting married or entering a monastery. Another initiative of Skarga – the brotherhood of St. Lazarus took care of beggars. The Jesuit was also a banking pioneer in Poland. At Mons Pietatis, or the Pious Bank, loans were granted to those who temporarily found themselves in financial difficulties. In return, various items were accepted as a pledge. In this way, the bank protected the poor population and counteracted usury, which was common at that time.

The image of a statesman concerned about the good of Poland, Skarga owed primarily to Jan Matejko, who suggestively portrayed the Jesuit in a scene where , inspired by a prophetic spirit, he prophesies the fall of the Polish Republic. “In the sovereign, governed and powerful Polish Republic, at the end of the 15th century, they began to appear like spots on a healthy fruit, the first ominous announcements of decay (…). We needed a doctor (…),” wrote Konstanty Wojciechowski in 1912. “The voice of a quiet, humble monk rose above everyone. His name is Piotr Skarga.”