After the introduction of martial law, the CIA launched a program to support the underground movement “Solidarity” with a budget of approximately $20 million. Throughout 1983-1990, money and specialized equipment flowed into Poland. In his book, Seth G. Jones pulls back the curtain on these sensational maneuvers.

by Tomasz Kozłowski

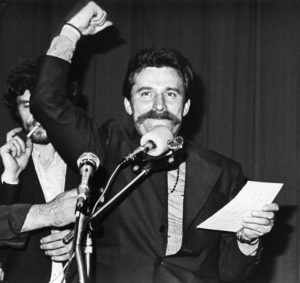

The emergence of “Solidarity” was a phenomenon in the Eastern Bloc. It was a gigantic trade union with almost 10 million members, which fought not so much for workers’ rights, but rather for the democratization of the system. The Central Intelligence Agency was surprised by the emergence of “Solidarity”, but quickly saw its potential. The union caused trouble not only for the leadership of the Polish United Workers’ Party, but also for the Kremlin. Moscow was afraid that the revolution might spread beyond the borders of Poland. That is why Leonid Brezhnev pressed Wojciech Jaruzelski, the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party, to introduce martial law and silence “Solidarity”.

When tanks appeared on the streets of Polish cities and thousands of Solidarity activists were interned, President Ronald Reagan recognized the importance of the moment. “This is the first time in 60 years that we have had this kind of opportunity. There may not be another in our lifetime. Can we afford not to go all out? I’m talking about a total quarantine on the USSR. Not detente!” roared Reagan at a meeting of the National Security Council. As a result, the White House introduced numerous economic sanctions. However, they did not stop there: the CIA began updating its anti-communist strategy. One of the elements of the resumed struggle was the launch of a support operation for “Solidarity”.

Title: A Covert Action: Reagan, the CIA, and the Cold War Struggle in Poland

Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

ISBN: 9780393247008

For years, US administration assistance to the democratic opposition has been the subject of speculation and suspicion. The book Victory. The Reagan Administration’s Secret Strategy That Hastened the Collapse of the Soviet Union by Peter Schweizer, published in the early 1990s, shed some light on this issue. The ideas presented in the book had repercussions. Zbigniew Bujak, the legendary activist of “Solidarity”, who in 1994 was an MP and head of the Sejm’s internal affairs committee, felt personally attacked. “On the basis of various information that is close and far from the truth, it can be concluded that during the conspiracy I accepted money from the CIA and was the holder of it in the country (…) The money was supposed to support the underground activity of Solidarity. This information is false,” asserted Bujak. At the same time, he was explicit that he accepted support from international trade unions and Western NGOs. A few years ago, the head of the so-called Polish desk at the CIA in the 1980s, Benjamin B. Fischer also addressed this issue.

Thirty years after the fall of the Iron Curtain, a book by Seth G. Jones now finally explores the background of the CIA operations. The book is based on declassified documents from the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, the National Security Archive, the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, the Hoover Institution, Polish archives, Soviet archives and the Churchill Archives Center.

Thanks to “A Covert Action”, it is possible for the first time to examine detailed data on the scale of financing provided to “Solidarity” by the CIA. During the operation (1983-1991), a total of approximately $20 million was spent. It is not a small sum, but it is not particularly impressive compared to the budgets for other operations. For example, $5 billion was spent for the (mainly military) support of the mujahideen fighting in Afghanistan. Fortunately, the CIA was not the only source of foreign funding for Solidarity. Money also came from individual donors, trade unions and the National Endowment for Democracy, which donated $9 million between 1984 and 1989. This diversification was in line with the CIA’s plan to stay in the shadows.

Already at the time of discussing the assumptions of Operation QRHELPFUL – as it was code named – it was assumed that it would have a limited reach: “Neither the CIA nor the White House officials expected U.S. covert assistance to overthrow the Jaruzelski regime or trigger a collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe (…) The goals were limited: to aid the organizational activities of Solidarity and other Polish opposition groups, improve their ability to communicate with the Polish people inside and outside the country, and put more pressure on the Jaruzelski regime to ease its repressive policies,” Jones writes.

Money and nonlethal equipment were sent to Poland, while Stinger missiles and anti-aircraft guns were sent to Afghanistan. In 1983, $2 million was spent as follows: “$600,000 for communications equipment, $300,000 for printing material, $100,000 to assist the families of Solidarity prisoners, over $500,000 for Solidarity members living outside of Poland, and more than $400,000 for propaganda.” However, even this support was problematic. The CIA did not want to alert Polish counterintelligence by initiating a sudden flow of cash, nor did the Americans want to be caught transferring money.

The CIA also supported Polish publishing houses in the West, such as “Kultura” and “Aneks”. In 1984, a huge media campaign with a global reach was created – it consisted mainly of inspiring writers and thinkers to write articles and in sparking solidarity actions in various countries, e.g. in Mexico. The network of intermediaries was systematically and patiently built up – the money was transferred from the CIA to organizations operating in Western Europe and to people who were involved in the further transfer of funds. With the help of collaborators recruited in the West, transit channels were created through which money and equipment were smuggled behind the Iron Curtain.

One of the most important collaborators was a man who hides in the pages of the book under the pseudonym “Stanisław Broda” (people familiar with the history of “Solidarity” may suspect whom the author is talking about). This oppositionist, who had emigrated to the West, cooperated on special terms, even by CIA standards – and acted partly outside the control of the Agency. The “CIA didn’t know all the specifics regarding who Broda worked with, what routes he used, and where the money or material ended up. Broda, who was strong-willed and fiercely independent, would never have provided that type of information anyway — even to the CIA — to protect his network, ”Jones writes.

Sweden was an exceptionally important channel for transferring materials and resources. It even happened that the head of the CIA, Bill Casey, personally asked Prime Minister Olof Palme for permission to conduct operations from his country. After obtaining approval, the CIA organized the entire operation. Broda shipped the materials to Sweden, where they were repackaged into containers labeled “tractor parts”, “machine tools” or “fish products”. There were also other tricks: “Broda’s most common technique, however, was to send concealed material on trucks, boats, ships, and tour buses arriving in Poland. One of Broda’s most ingenious inventions was a reconfigured refrigeration truck that had a dividing wall and a hidden compartment that could fit up to ten offset printers,” Jones writes.

It is worth emphasizing – the CIA avoided recruiting people active in Poland, especially the leaders of “Solidarity”. This was due to the fear of them being exposed as “America’s puppets.” John R. Davis Jr., Chargé d’Affaires ad interim since September 1983, recalled: “The one thing I was afraid of was that the Solidarity leadership would get pinned as foreign agents. (…) I did not want the Polish government to be able to say or prove that, ‘Here is, you know, Geremek, talking to a CIA agent. These people are not true Poles; they are acting as agents of the United States.’”

Despite precautionary measures, the CIA’s involvement did not go unnoticed. The KGB was convinced that the CIA was sponsoring the opposition in Poland. This opinion was shared by the Polish Security Service. General Władysław Pożoga, deputy minister of internal affairs and head of intelligence and counterintelligence, stated in 1985 that the CIA had increased support for “Solidarity”. “For this purpose, communication channels with [the] underground are being created and expanded, through which more and more cash flows, as well as highly specialized equipment and accessory,” he explained. He indicated that couriers with large sums of cash or expensive printing and communication equipment were more and more often captured.

Pożoga was afraid that activists of “Solidarity” at home and abroad were more and more specialized in conducting underground activities: “they use codes and secret messages in communication with the underground (…) conspiratorial structures in the country are supplied with computer communication systems.” The speech of the intelligence chief was commented on by the then Deputy Prime Minister Mieczysław Rakowski: “As far as intelligence activities are concerned, there is no doubt that it exists, it would be strange if it did not exist. Incidentally, I believe Poland was so penetrated by the intelligence service that if you could look into these safes that are in various spy stations, we would be really amazed.” However, no one caught the CIA red-handed.

Seth G. Jones’s book presents a broad picture of the activities of the American administration in the context of the conflict between the communist authorities and “Solidarity”. A broad perspective and fragments explaining the intricacies of Polish history may be moderately engaging for an informed, domestic reader, but they will be enticing and absolutely necessary for a foreign audience. The author tries to apply a journalistic style, which undoubtedly makes the book more readable.

The book is not free from certain errors and omissions, as exemplified by the issue of Lech Wałęsa’s cooperation with the Security Service. Such cooperation took place before he made his debut as an oppositionist. Although the historical environment is broadly consistent in the assessment of this episode, it is presented in the book quite ambiguously. The Polish reader will also be amused by some fragments of the book, e.g. those concerning the biography of Wojciech Jaruzelski. Some of the errors resulted from imperfect translation. However, this does not change the fact that the book is important, sensational and worth recommending. It is strange that it has not received much attention in Poland so far.

Author: Tomasz Kozłowski – PhD in political sciences, employee of the History Research Office of Institute of National Remembrance

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin