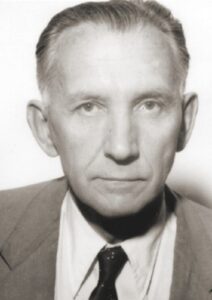

The main message of Sukiennicki’s biography is intellectual independence won even at the price of marginalisation and isolation, fidelity to the belief that research can show the truth about the world, says Professor Sławomir Łukasiewicz.

polishhistory.pl: Wiktor Sukiennicki is a figure of great merit for Sovietology and the understanding of the functioning of the Soviet Union. What do we know about his family home and adolescence?

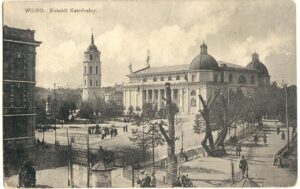

Sławomir Łukasiewicz: Let us begin with the fact that 25 July 2021 marks 120 years since Sukiennicki’s birth, which provided a great opportunity to remember him. He came from an impoverished landowning family. Unfortunately, his parents separated almost instantly, so Wiktor was brought up by his mother, Janina née Kobylińska, a physician. He was born in Aleksotas (Polish: Aleksota), which used to be a village near Kaunas, and is a suburb of the city today. Following the outbreak of the First World War, he and his mother moved to Rybinsk on the Volga River, where he attended a Russian school. When Stephen Báthory University (SBU) in Vilnius was re-established in the newly independent Poland, Sukiennicki took up his legal studies there.

What were his subsequent years at the university like?

They were by no means standard, peaceful studies. As early as 1919, he joined the Polish Military Organisation and, after a few months, set off for the Polish-Bolshevik war. In 1922, he married Halina Zasztowt, and together they studied law at the SBU. Already at the beginning of his studies, in reference to the Mickiewicz tradition, Sukiennicki attempted to create the Filaret Association. When he did not receive permission from the university authorities to use this name, he founded the Association of Progressive Youth. This organisation attempted to act on behalf of the Jewish youth and other national minorities, who were facing various types of harassment. Throughout his life, Sukiennicki was of the opinion that people should be respected regardless of their origin, religion, or views.

With such intense social activity, did he manage to complete his studies?

Of course! In 1926, a year that was also significant for Poland, he wrote and defended his doctoral thesis at the Paris Sorbonne, on a subject that was very modern for those times. He analysed the question of state sovereignty in the light of international law. Today, every political scientist will say that the category of absolute sovereignty postulated by Jean Bodin back in the 16th century does not exist. It was not obvious at the time, and the importance of Sukiennicki’s insights was immense; indeed, he was awarded a prize for his doctorate by the Paris Sorbonne. It is regrettable that his contribution to sovereignty thought is not more widely known today.

He then travelled around Europe – he studied in Vienna, Rome, and Cologne, in Vienna with Hans Kelsen, among others – an excellent legal theorist who would be a source of inspiration for him in the future. He then returned to Poland and, in 1929, defended his habilitation thesis on ‘The foundations of the validity of the law of nations’. This is the beginning of his scientific path. Please note that, at the time of his habilitation, Sukiennicki was merely 28 years old.

But after that, did his rapid career slow down somewhat?

The main problem was related to the academic environment in Vilnius. It was not entirely open to Sukiennicki’s revolutionary views. The source of disagreements was the abovementioned issue of sovereignty. If, in the mid-1920s, someone like Sukiennicki put forward a premise that (at least in the eyes of superficial readers) denied the existence of sovereignty, it was unacceptable to Poles, who, only a few years earlier, had regained independence after more than 120 years. His involvement in the defence of the minorities was also resisted, especially in the 1930s, when nationalist tendencies were growing, and the view was put forward that mono-ethnicity would be desirable for Poland. Sukiennicki did not think so, and differed from many professors in Vilnius in this respect.

Yes, he did lecture at the SBU at that time, but he did not have a permanent contract or the formal status of a professor: his contract was renewed every year. And it was at that time that an institution was established in Vilnius that opened up new perspectives and an unexpected career path for him. This was the Research Institute for Eastern European Studies (Instytut Naukowo-Badawczy Europy Wschodniej). Sukiennicki’s work at this institute is the cornerstone of his scientific biography.

Sukiennicki took a relatively late interest in Sovietology. The subjects of his PhD and habilitation theses indicate that he was initially far from dealing with Eastern issues. Could his interest in international law have influenced his change of interest?

This is a very good question. But we must answer another: what does it mean that he took a late interest in the subject? Since being awarded his PhD title at the age of 25, and his habilitation three years later, he began to deal with the Soviets in his thirties. This is by no means ‘late’, although he was indeed first interested in the problems of international law and sovereignty. Let us remember that this was a time when the League of Nations was being born, and the principles of its functioning, the tasks and priorities facing it, and the issue of the extent to which states could surrender their own sovereignty in favour of supranational actors, were being discussed. At that time, Aristide Briand and Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi were championing the notion of pan-Europeanism, so Sukiennicki’s interests were very up-to-date, and resonated with the discussion among politicians and scholars at that time.

In order to establish the beginnings of his interest in the Soviet Union, it is necessary to take into account the fact that his wife, Halina Zasztowt-Sukiennicka, was simultaneously defending her PhD thesis at the Sorbonne, which concerned the federalist movement in Eastern Europe and the Soviet constitution. After all, they studied together, and I cannot imagine that they did not talk about the Soviet system. Thus, the other issue very much alive in the Sukiennicki family was federalism – understood as a tradition rooted in Polish history, but also as an idea for the unification of Europe and, at the same time, federalism, which was enshrined in the Soviet constitution. These were undoubtedly the topics preceding Sukiennicki’s later interests, which, combined with his thorough preparation in international law, bore fruit during his work at the Research Institute for Eastern European Studies.

Please note that, in the 1930s, the Soviet Union became a serious international problem. For Poland, it was an increasingly dangerous neighbour, so the need to explore the essence of that state’s system was an obvious research challenge, requiring thorough study.

What I found interesting and innovative in Sukiennicki’s work was the relegation to the background of moral and political issues. Instead, he emphasised the generality and fluidity of the rules, which gave wide scope for interpretation, rendering the Soviet system itself dynamic.

I would caution against presentism: the moral evaluation and condemnation of the Soviet system appeared relatively late in scholarly writing. Such a paradigm was born with Hanna Arendt’s studies on totalitarianism, Carl Joachim Friedrich’s book, and the one by Zbigniew Brzeziński, which made it possible to perceive the Soviet system in black-and-white categories. It was also influenced by the experiences of the Cold War, the activities of the Madden Commission investigating the Katyn massacre, McCarthyism in the United States and, finally, the admission of a fatal omission – the failure to punish Soviet crimes following the example of the Nuremberg trial.

In the post-war years, many studies were written to expose the propaganda image of the Soviet Union as a workers’ paradise, showing it was a state that destroyed its citizens, imprisoned them in gulags, and carried out mass-scale murders for trivial reasons. Over time, the world came to realise that the Soviet state did not meet any moral criteria. But this was not at all obvious in the 1920s and 1930s, except perhaps to those thinkers who assumed structural similarities between the Soviet Union and Tsarist Russia, and were critical of the latter.

When Sukiennicki commenced his research, the only thing that was clear was that a revolution had taken place in Russia that proved to have lasting effects. But what was it? Perhaps a similar transformation to that in 18th-century France? The Soviet Union, which the scholar began to explore, was an enigma that did not reveal its secrets to the Western world. The rulers at the Kremlin were able to communicate with the Weimar Republic and other states, so it seemed that the Soviet system was as suitable for observation as any other state in the world. Let us also remember that Western Europe behaved ambiguously during the revolution, helping different sides. However, due to the Poles’ knowledge and experience with the Russian state, their experiences from the First World War, and finally from the war with the Bolsheviks in 1920, new questions began to arise.

In 1934, Sukiennicki visited the Soviet Union. What did he manage to see?

He was able to see various official documents, but one can hardly expect that this visit allowed him to delve into the essence of the system, that someone showed him the gulags and unimaginable poverty. He was shown investments and developing science, as well as presented with modernisation concepts that could not necessarily develop in Tsarist Russia. The only thing he could do on his return was to apply legal analysis to the reality he found. But he went further, as can be seen in his student Franciszek Ancewicz, for instance: he analysed the legal reality and compared it with the conclusions of official documents. And only then could the differences be shown beyond any doubt. His work from the 1930s is an amazing achievement: he developed a method by which, in the absence of access to knowledge about Soviet reality (at that time, such data could only be obtained through intelligence), he managed to prove the existence of discrepancies between declarations and the actual standard of living in the Soviet Union. Using the methods developed by Kelsen and adapted for the field of Sovietology, Sukiennicki and his team were able to distinguish between the imaginary reality (functioning at the level of declarations and documents), and the actual reality, i.e. all the phenomena hidden beyond the sphere of propaganda.

Did the professor have an opportunity to become acquainted with the Soviet reality in its less ‘showy’ version?

He was taken prisoner by the Soviets, miraculously survived and, after 1941, when the USSR joined the anti-Hitler coalition, and Moscow established relations with the Polish Government, worked for the Polish embassy. He searched for missing officers, researched the fate of those who had disappeared after being interned by the Red Army and the Soviet security services in the autumn of 1939. All this brought him another dose of knowledge about the Soviet Union. He understood that this state was capable of committing a huge crime, murdering thousands of Polish officers and intellectuals, who disappeared without a trace.

Do you mean the Katyn massacre?

Yes. Today we know the history of the Katyn investigation, in which Sukiennicki played a huge role. He prepared a report for the Polish Government, as well as materials that were to be used in Nuremberg against the Soviets. A strictly legal analysis was possible before the war, but his own observations, experiences and collected accounts, changed the way he wrote about the Soviets. This was augmented by the experiences of his colleagues, for example Stanisław Swianiewicz and Władysław Wielhorski, who were associated with Vilnius. These experiences grew into a generational experience. Sukiennicki did not ignore this in any way. In addition to his legal analyses, he also began to take into account the statements of politicians, and thus began to analyse the functioning of the Soviet Union’s practices. Perhaps surprisingly, it was only toward the end of his academic career that he discovered himself as a historian, and found that he was most interested in the story of the past. This is demonstrated well in his text on Khrushchev. In it, he traces the idea of ‘Khrushchevism’, somewhat avant la lettre, as it were, starting from Marx’s writings….

In Poland, we could observe that, when one communist team replaced the preceding, discredited one, it proclaimed a renewal of political life in the Leninist spirit. Behind such a vision of renewal stood the conviction that it was not ideology that was wrong, but people who made mistakes. This attitude makes us laugh today, because it seems hypocritical to us. I do not think, however, that it amused Sukiennicki. He saw the differences between the programme of a revolution in the Marxist spirit, propounded by Lenin, and the subsequent practice of the bureaucracy. He himself wrote that the USSR had not created socialism, but a bureaucratic apparatus of a previously unknown kind.

Fully agreed. It is to Sukiennicki’s credit that he raised this issue as part of his systematic research, wondering already in the 1930s whether socialism ‘fitted’ the Soviet Union at all. Was the 1917 revolution, to use Marxist terminology, an element of historical development, or was the ideology tailored to the political situation in Russia and the seizure of power? Sukiennicki made himself (and his readers) aware of the difference between how Marx and Lenin perceived reality.

What do you mean?

Marx observed Western reality, whereas Lenin had to apply the doctrine, created with Western European economic and political reality in mind, to Russia in some way. There, meanwhile, with the exception of the few ‘urban islands’, was practically no large-scale proletariat as an effect of industrialisation. Legal studies were ideally suited for this kind of comparativism; through them, it was possible to understand the variability of the adaptation of ideas. This is well illustrated by the example of Leninism: can we speak of a coherent ideology of Leninism at all? Stalin, Vladimir Ilyich’s successor, hid some of the latter’s output and writings, changed others, while successive editions of Lenin’s writings were censored and tailored to the needs of propaganda. Sukiennicki was familiar with the following versions of these writings, and addressed the detailed problems by pointing out the discrepancies in the long run.

In theory, communism was supposed to be based on the role of the masses, but in practice it was quite the opposite – all forms of social control were removed. Was it possible to conclude from the data collected by Sukiennicki that reality was a reversal of theory?

This question goes back to the essence of the Bolshevik revolution, and the structure of the Soviet state, including the power that appropriated the structure of the state. It was the party that decided on legal practice, while the proletariat, which was to exercise control in the state, had to submit to party control. There were more of these absurdities and perversions. Lenin and Stalin were able to contradict their earlier declarations, even their doctrinal dogmas, within a few months, just to achieve a certain political goal – and for Sukiennicki this was obvious. The Soviet state, drawing on Marxism, created mechanisms directed against its own society and contrary to the European tradition. This observation is particularly interesting as a basis for Sovietology, and it aroused an understandable aversion to that system, while it was not fully understood, for example, by part of American Sovietology.

What determined that his brilliantly promising and developing career slowed down, and that the positions he held did not match his talents and skills?

We have talked about the fact that he was habilitated in 1929. Ten years later, when the war broke out, he was 38 years old – under normal circumstances he would have obtained a full-time position at the SBU, and would likely have been a nationally and internationally respected Soviet system specialist. The war shattered the careers of scholars, artists, and activists – most expected that it was just a state of limbo, and that they would return to Poland. In the case of Sukiennicki, if he wanted to return, it would be to his Vilnius. However, after the war, the city was already part of the Soviet Union. When migrating, Professor Sukiennicki always gave his Vilnius address when asked where he lived. He always wanted to return there, but also knew that it was impossible. The situation was similar for hundreds of thousands of Poles, who were either unable to return to the USSR, or to Poland governed by the communists.

How did Sukiennicki manage in exile?

He worked for the Polish Government-in-Exile and at the embassy, so his competences were used. In the following years, he lectured at the Polish Faculty of Law at Oxford University, at the School of Social Sciences in London, and, together with his wife, initiated an alumni organisation at the SBU. But these activities did not build his political career, and were merely a substitute for an academic one. The Polish Faculty of Law was soon closed, and the School of Social Sciences lost its original impetus. In 1952, the opportunity arose to work at Radio Free Europe. There, he hosted two series of programmes – one entitled Za murami Kremla [Behind the Kremlin Walls], where he acted both as a Sovietologist and a Kremlinologist, and the other devoted to European unity. This took a total of seven years of hard, analytical work.

Between 1939 and 1959, he worked mainly for the Polish Government, and wrote mainly in Polish. From the point of view of his academic career, this time can indeed be considered a waste. Aged almost 60, he allowed himself to be persuaded to seek work in the United States. His command of English was poor, yet he had the courage to leave. He knew German, French, and Russian very well. Had he gone to France, he likely would have had the chance to return to his legal interests. However, he chose to remain in the expatriate community despite not always identifying with it. He had his own narrow social circle, but in everyday life he was rather a recluse.

In the 1960s, he wrote bitterly that he did not consider himself either a Catholic, a Jew, a National Democrat, or a follower of Piłsudski, and he did not fit into the usual political and religious patterns. ‘If I’d fitted in, I would likely have gotten something,’ he wrote, complaining that no specific milieu had attempted to solicit him. However, he retained very strong friendships until the end of his life, e.g. with Wiktor Weintraub, who, having taken up the chair of Slavic Studies at Harvard in the early 1950s, urged Sukiennicki to come to the USA.

The last 20 years of Sukiennicki’s life can be described by the title of the forthcoming article, i.e. ‘The homelessness of a Sovietologist’. Naturally, Sukiennicki had somewhere to live, but he lacked a sense of belonging.

I discovered that, in the 1960s, Sukiennicki produced 30 massive reports for the Hoover Institution on the Comintern and the Soviets: that is an average of three to four reports per year! All this was to be used by other scholars for their own research. These reports never saw the light of day, as Sukiennicki had predicted. In the archives of the Hoover Institution, he searched for answers about the causes of the outbreak of the revolution, and the fate of individual states and nations at that time. The fruit of these interests was his last book, written in English. At the age of sixty, he made the decision to prepare a book in a language he did not know very well!

He stopped analysing current affairs in the Soviet Union – the aforementioned studies on ‘Khrushchevism’ were among his last works in this field. He published a type of memoir – Legenda i rzeczywistość [Legend and Reality] – with Giedroyć, but, at the same time, began to focus on historical aspects. In this sense, he did not depart from Sovietology, but changed his perspective. In essence, he did what Richard Pipes did for Russia, only Central and Eastern Europe remained in his circle of interest. In a letter to Swianiewicz, he even wrote that he had discovered a historian in himself at an old age.

Why did Sukiennicki fall into oblivion so quickly?

He used cool, balanced academic language in his publications, which led to accusations of pro-Soviet sympathies. The fact that he failed to participate in mainstream scientific debate from 1939 onwards meant that his work was marginalised. He reminded Poles of himself through his work with Radio Free Europe, and the Paris-based Kultura, but his departure for the United States left him condemned to marginalisation. On the one hand, at his age, a career in academia was out of the question and, on the other, he distanced himself from the Polish diaspora in London. In the People’s Republic of Poland, apart from people connected with the Vilnius academic centre, and a group of historians, he was hardly known to anyone, and officially did not exist.

How can his writings be useful in understanding the Soviet Union today?

The scholar died in 1983. After the transformation of the political system, his works were not revisited until studies on Polish Sovietology began to emerge. It is to the credit of Professor Marek Kornat and others, who reminded us of the strength of Sukiennicki’s environment by publishing texts on him, including his biography in the Polish Biographical Dictionary. I was lucky to meet Czesław Miłosz, who also talked about Sukiennicki, and his student and colleague from Vilnius, Franciszek Ancewicz. But it is one thing to recall the traditions of the Polish school of Sovietology, and quite another to understand him and propagate his thought outside of the academic milieu. The fate of Sukiennicki was dramatic and his promising career was halted. His pension from the Hoover Institution amounted to a mere $14, to which some minor remunerations for lectures and royalties were added. This is certainly not a biography that can be treated as encouraging for the young.

His life undoubtedly deserves to be remembered. His efforts in establishing the science we call Sovietology, in studying the Katyn issue and educating people, must be appreciated. The main message of his biography is intellectual independence won even at the price of marginalisation and isolation, fidelity to the belief that research can show the truth about the world. This is particularly noteworthy, although, unfortunately, difficult to emulate. With his bold concepts and analytical sense, he was undoubtedly ahead of his time.

Interviewer: Piotr Abryszeński

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki