In the evening of the 17th of January 1945 in Moscow, 24 cannon salutes were fired to celebrate the capture of Warsaw. After 75 years the Russian government is replicating this gesture by organizing a firework show – along with the same salutes. Sadly, Kremlin is not only copying old gestures, but also returning to the old statements of Stalinist propaganda.

by dr Łukasz Kamiński

The interpretation of the events of 1944-1945 as a “liberation” of Poland, promoted by the Russian government, clashes with the Polish memory. It is sometimes hard for bystanders to understand why Poles removed the monuments of “gratitude” for the Red Army from their towns and cities.

Let us look at those events from the Polish perspective. It requires recalling a few facts from the history of the World War II. The fate of Poland, along with that of some other Central European countries, was determined by the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact, signed on the 23rd of August 1939. It’s secret annex divided this part of the continent into zones of influence. On the 1st of September 1939 Germany attacked Poland, and on the 17th of September the Soviet Union joined the invasion. Before the last battles ceased, the totalitarian allies signed a new treaty, this time “of borders and friendship”.

In September 1939 Polish citizens heard for the first time that the Red Army had come to “liberate” them – in that version, from the oppression of the bourgeoisie. Soon, other nations learned the taste of this “liberation”. The Soviet Union attacked Finland later in 1939, in 1940 it annexed Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and a part of Romania. All those acts of aggression were based on the Soviet-German agreement. The other side profited from it as well. While Hitler attacked subsequent European nations, the Soviet Union sent shipments of necessary resources. While Adolph Hitler ceremonially received the Soviet Foreign Affairs Minister Vyacheslav Molotov (November 1940), the Auschwitz concentration camp had been operational for almost half a year.

The Soviet Union captured over a half of the Polish territory. The Soviet occupation meant mass repressions and crimes – most prominently the Katyń Massacre (over 21 thousand murdered) and deportations, during which over 320 thousand people were sent to the East. Only the German attack of June 1941 led Moscow to change the policy towards Poland. Diplomatic relations were strengthened, and a stem of a Polish army was formed from released deportees and prisoners of the Gulag.

However, it soon turned out Stalin didn’t mean to keep the agreement signed with Poland. It caused the Polish troops to leave the Soviet Union. Ultimately the Kremlin used the excuse of the Polish government asking the International Red Cross to investigate the graves discovered in Katyń to break diplomatic relationships with Poland in the end of April 1943. At the same time a future government, subservient to Moscow, was already being built.

The first troops of the Red Army entered the Polish territory on the 4th of January 1944. From the beginning it was treated as a part of the Soviet state. It not only meant that Moscow broke the Atlantic Charter, but de facto confirmed the previous agreements with the Third Reich about partitioning Poland. Ultimately Poland was given back most of the pre-war Białostockie Voivodship, which constituted less than 10% of the areas taken in 1939.

The fate of the troops of the Home Army fighting the Germans became a symbol of the Soviet policy. They participated in, among others, the fights for Vilnius and Lviv. After the fighting ceased, officers were insidiously arrested and soldiers interned. A similar fate awaited the civil officials of the Polish Underground State. Repression also continued in territories Stalin planned to leave to Poland (west of the Bug river).

On the 20th of July the Polish Committee of National Liberation (PCNL) was created in Moscow to govern these territories. In the next decades propaganda maintained that it happened two days later in Chełm, to build an appearance of an independency of the puppet government. The PCNL was only recognised by the Soviet Union, other countries maintained diplomatic relationships with the legal government-in-exile.

In such circumstanced the decision to start an uprising in Warsaw was made, on the 1st of August 1944. Despite the heavy fights against Germans, Stalin at first maintained that Warsaw was in peace, and later called the uprising a “rumpus”. The leaders of the Polish underground were targeted by the Soviet propaganda. Moscow not only withheld its offensive, but also denied the Allied planes dropping supplies landing, which caused immense loses among those coming from Italy. This policy was only changed in the middle of September, when the uprising was already failing.

At the same time mass repressions were directed against soldiers and officials of the Polish Underground State in areas controlled by the PCNL. They were mainly conducted by the Soviet NKVD and the military counterintelligence Smiersz, with participation of the communist security structures created by Soviet advisors. It was grimly symbolized by the fact that after only a few days after the German concentration camp in Lublin’s Majdanek was taken, the NKVD adapted it as a filtration camp for members of the Polish underground. Soon after the massacre done by retreating Germans in the Lublin Castle, the cells of this prison were full again. Dozens of resistance heroes were executed basing on unlawful sentences.

Despite the repressions the resistance against the regime imposed by Moscow lasted. An attempt was made to suppress it by an escalation of terror. The decree on “protecting the state”, proclaimed in the end of October 1944, allowed for a death penalty to punish all eleven crimes listed in it.

In the middle of January 1945 another Soviet offensive was launched. On the 17th of January, with little German resistance, the ruins of the left-bank Warsaw were captured. Soon all Polish territories were under Soviet control. The mood of that time is well described by the note in a famous writer Maria Dąbrowska’s journal: “in the morning the Germans were still here, and in the evening we are under Bolshevik occupation”. The joy of ending the cruel German occupation intertwined with other feelings. The reports from that time speak about numerous rapes by Soviet soldiers on women and girls of every age, robberies (especially of watches and bikes), and even murders on civilians. In some cities, such as Katowice, buildings that survived the fighting were purposely burned down. Next to individual robberies, organized ones took place – the equipment from entire enterprises was taken to the Soviet Union.

It is characteristic to the Soviets that one the first things they did after taking Warsaw was establishing operational groups meant to find the members of the underground, especially the leaders. The formal dissolution of the Home Army (19 January) did not stop these actions. The repressions also affected civilians. 50-60 thousand people were taken from Pomerania and Silesia for forced labour to the USSR, regardless of them being citizens of Poland or Germany before the war.

In February, during the Yalta conference, the powers decided the fate of Poland. Stalin’s territorial demands were accepted, in return offering a part of the German territory to Poland. A decision was also made to establish the Provisional Government of National Unity, which was to organize a free election. Those decisions were rejected by the Polish government-in-exile, which said that the declaration was a “new partition of Poland, this time done by the hands of our allies”.

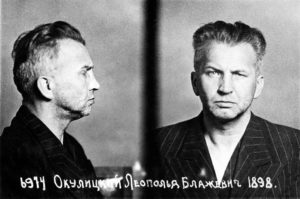

The leaders of the conspiracy, despite criticizing Yalta, declared readiness for negotiations on creating a new government. However, Stalin did not mean to let them participate. In the end of March, the leaders of the Polish Underground State invited for the talks were imprisoned and sent to Moscow, where they were placed in the Lubyanka NKVD prison. Among them was the last commander of the Home Army gen. Leopold Okulicki, deputy prime minister and government delegate for Poland Jan S. Jankowski and chairman of the Council of National Unity (underground parliament) Kazimierz Pużak. For a few weeks the USSR government maintained that their location is unknown.

The show trial of the Polish leaders took place in Moscow in June 1945. To humiliate them, and all other Poles fighting the occupant, they were convicted of, among others, cooperating with the Germans. The sentences were relatively mild (up to 10 years of prison), but three convicts (Okulicki, Jankowski and the deputy government delegate Stanisław Jasiukowicz) died in prison in circumstances that were never explained. Others were imprisoned again after returning to Poland ruled by communists.

It was not a coincidence that this process took place at the same time as the talks about creating the Provisional Government of National Unity. It had only one member not connected with Moscow – ex-prime-minister-in-exile Stanisław Mikołajczyk, along with a few associates. During the talks one of the communist leaders, Władysław Gomułka, spoke the historic words: “Once we have power, we will never give it away. […] You may keep shouting that the blood of Polish nation is being shed, that the NKVD rules Poland — it will not cause us to turn in our course.”

Poles held high hopes for the return of Mikołajczyk, believing that regaining freedom and independence would be possible. However, this didn’t happen. Only a few days later, in the middle of July tens of thousands soldiers of the 50th army, a part of the 3rd Belarusian front, and 62nd NKVD division organized a huge operation in north-eastern Poland, known as the “Augustów roundup”. 7 thousand people suspected of cooperating with the underground were arrested, 600 of them were killed in a place still unknown.

At this time monuments of “gratitude” for the “liberators” from the Red Army were already being raised from the initiative of the Moscow-imposed government. Simultaneously thousands of heroes from the war were in prisons or Soviet camps, many others were murdered by those “liberators” or their local henchmen. Others remained in conspiracy or in emigration. The true feelings about the monuments erected without the Poles’ will were represented by numerous attempts to destroy them.

NKVD troops were stationed in Poland until 1947, and the Soviet army remained until 1993. Soviet soldiers ended the German occupation, but they didn’t bring freedom, simply new oppression. The fight with the communist dictatorship lasted many years, bringing new victims. Freedom came only after the victory of “Solidarity”.

Author: Dr. Łukasz Kamiński – the President of the Platform of European Memory and Conscience and former President of the Institute of National Remembrance from 2011 to 2016.

Translation: Jakub Kamiński