“This means war. From now on, all other matters and issues become of secondary importance”, stated the message broadcast by Polish Radio on the morning of 1 September 1939. “We set our public and private lives on a special track. We have entered war. The entire effort of the nation must go in one direction. We’re all soldiers now. We need to think about only one thing: fighting until we win”. German aggression against Poland had begun the Second World War, a conflict that would consume 70-85 million lives over the next six years.

by Piotr Abryszeński

Poles had enjoyed a free state for a little over twenty years. Independence had been the dream of generations of Polish patriots, whose homeland had been taken from them as the result of partitions by neighbouring powers. When Poland regained its sovereignty, after 123 years and as a result of the First World War, it energetically began to rebuild social, cultural and political life. The revived state first faced a deadly threat from Bolshevik Russia, which, due to mobilisation of the entire society, it was able to throw back. When the borders of Poland had finally been established and confirmed, its inhabitants could at last enjoy their regained freedom and live in their own country.

From memoirs and diaries of that period, we learn that summer 1939 was extremely hot. On period photos and postcards, you see crowds of smiling tourists and holidaymakers dressed in the fashion of that day. In the evenings, cafes and restaurants were crowded with regular guests, who would also visit cabarets and variety shows. In Warsaw alone, where a million people were living, there were 60 cinemas, big enough to accommodate thousands of viewers.

By autumn 1938, Hitler had already demanded that Poland consent to including the Free City of Danzig in the Third Reichm, while delineating an extraterritorial highway and railway line that connected Danzig with Germany across the northern Polish region of Pomerania, or the “Pomeranian corridor” that the Germans dismissively referred to. Poland, rejecting Berlin’s demands, formalised an alliance with France and Great Britain. Unfortunately, the Polish-British treaty of 25 August 1939 did not halt the coming invasion, only postponing the attack by Germany. Rapprochement with Great Britain and France had an important basis: it was a sign that Poland, faced with changes in the international arena, was supporting the West and rejecting offers of any cooperation with the Third Reich.

But at the end of August, Polish towns and cities still did not believe in war breaking out. It was widely believed that Berlin’s threats were only the megalomania of the German government. Jokes about Hitler and his associates were repeated in the press and on radio, and popular Warsaw cabarets, those in both Polish and Yiddish, presented the latest jokes and mocked screaming speeches by the Chancellor of the Third Reich. People believed instead in the Polish military, and believed in allies and in the League of Nations as the guardian of world order.

It was rather different in Pomerania. The amount of Polish tourists at the seaside was lower than in previous years. Also noticeable were the concentration of German troops and heightened traffic across the border between the Third Reich and the Free City of Danzig. The atmosphere was more serious, as numerous acts of violence had long been happening against the Polish population there. Anti-Polish sentiments were skillfully fueled by propaganda directed by Joseph Goebbels. When Polish customs officers arrived in mid-August 1939 in Stutthof (now Sztutowo, a village on the Baltic coast, located about 38 km east of Gdańsk, at the base of the Vistula Spit), they observed preparations for construction works. They did not know that, under SS supervision, a concentration camp was being built there, which according to the original planning would have been larger than the sinister Auschwitz would grow. Already on 2 and 3 September, the first transports of prisoners to KL Stutthof took place. Among the first were members of the Polish intelligentsia and the clergy, soon joined by Jewish prisoners arrested in Gdańsk and nearby Gdynia.

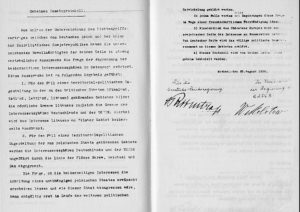

On 23 August, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact. Executing the wills of their leaders were the foreign ministers of both countries, Joachim von Ribbentrop and Vyacheslav Molotov. That agreement shocked public opinion globally. A secret additional protocol of the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact contained a provision on the division of the Polish state along the Narew, Vistula and San Rivers. Polish historiography now defines this pact as the “fourth partition of Poland” [in reference to late 18th-century partitions]. The German-Soviet alliance also meant police cooperation, resulting in plans to exterminate Polish elites.

On the evening of 31 August 31, an SS unit and a group of criminal prisoners dressed in Polish uniforms faked an assault on a German radio station in Gliwice, a city in Upper Silesia, in the south of Poland. This “Gliwice provocation” then became an excuse for aggression against Poland.

On 1 September at 4:45 in the morning, from large-caliber cannon aboard the battleship Schleswig-Holstein then on a courtesy call in Gdańsk, heavy shells were fired at the Polish military depot on the Westerplatte peninsula. The first of many battles of the Second World War began. The depot crew was under orders to defend themselves only for a few hours, but managed to withstand seven long days of exhausting shelling and air attacks. Defenders under the command of Major Henryk Sucharski and Captain Franciszek Dąbrowski lacked sleep and drinking water. The message broadcast by Polish Radio. that “Westerplatte is still fighting”, encouraged millions of Poles, and that fierce resistance by the few became a symbol and inspiration for those fighting in the days and years that followed.

Heroic defense of the Polish Post Office in Gdańsk, under attack by armed SS and SA troops on the morning of 1 September, has grown into a symbol. The postmen capitulated only after 14 hours of fierce fighting. A month later, they fell victim to judicial murder, and they were shot. Another meaningful symbol is the attitude of the Warsaw’s defenders in their civil resistance, as well as the resistance of the city’s president, Stefan Starzyński. In response a proposal to help him flee from the city, Starzyński replied that he wanted to remain among the people of Warsaw. His radio speeches encouraged them to defend the Polish capital. After his arrest, he shared the fate of many Polish politicians, scientists and representatives of the intelligentsia: he was murdered by the occupying forces.

An American correspondent in Warsaw, witness to the ruthless bombing of the capital, wrote in a dramatic appeal addressed to the president of the United States and to his compatriots: “None of us gathered here can understand this unrestrained murder of the Polish civilian population. There can be only one explanation. This is must be calculated for a complete devastation of the fighting spirit of the Poles. And what is most surprising – the aggressor did not succeed. Neither Polish soldiers nor civilians, men and women behind the front line, give up.”

The German attack on Poland followed a strategic plan codenamed Fall Weiss, adopted in April 1939. It assumed an attack on Poland without declaring war, on three sides: from East Prussia in the north, along the western border and from the south through German-controlled territory by Slovakia, and with the participation of its troops. The idea was to launch a new type of attack: the Blitzkrieg, that is, lightning war. According to Hitler’s assumptions, conflict with Poland would last for two weeks. The last Polish troops, under the command of Gen. Franciszek Kleeberg, laid down their weapons on 6 October after the Battle of Kock in eastern Poland – the final battle of the invasion of Poland.

Gen. Władysław Anders recalled: “I see a German aviator circling over a crowd of hundreds of small children, being led by a teacher from a town to a nearby forest. It descends 50 meters, drops bombs and fires with a machine gun. Children scatter and jump away like sparrows, but a dozen or so coloured spots remain in the field. I have a foreshadowing of what this war will be like.” Anders was right. The war was marked by the deaths of millions of soldiers – but first and foremost was a suffering among the civilian populations that was previously unknown. A soldier must face death on the battlefield, but ordinary people can never be prepared for it. The invaders showed no mercy to anyone: defenseless children, women and the elderly. No one could have guessed that in lands it was then occupying, Germany would soon commit crimes such as human history had never seen.