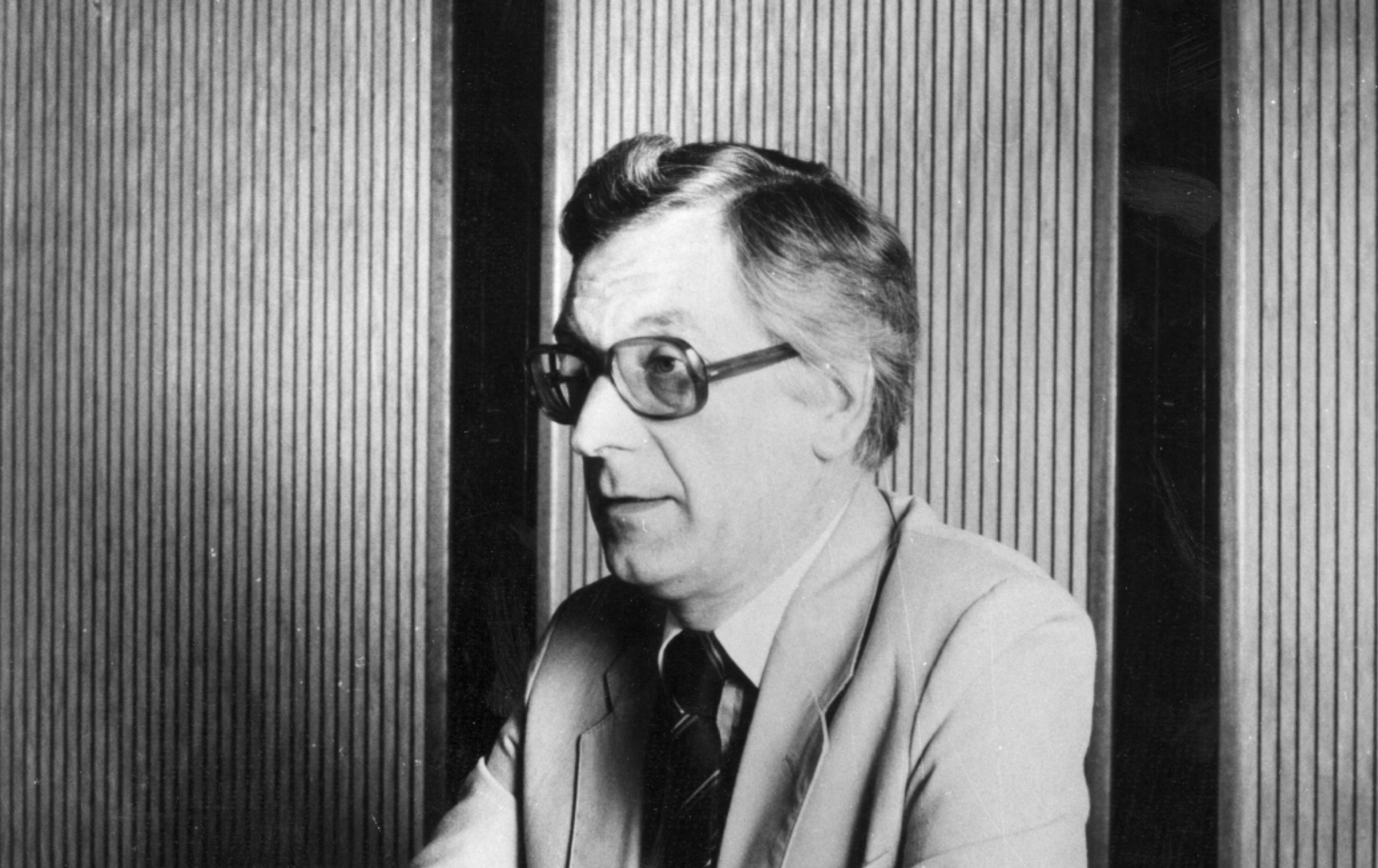

Philologists are relatively rarely sentenced to death in absentia. Nor do they always (although somewhat more often) become Chevaliers of the Legion of Honour. This alone shows how remarkable was the fate of Zdzisław Najder, who died on 15 February 2021.

by Wojciech Stanisławski

In the mid-20th century, it seemed that – comparing with other people born in Poland around 1930 – fate was relatively kind to him. He survived the war and occupation, was not deported to Siberia and did not become an orphan. Despite his ‘inappropriate’ background (a wealthy Warsaw family, additionally linked to the Polish Socialist Party), he was not repressed and was even allowed to enter university. Later, however, events accelerated somewhat.

In all seriousness: Najder belonged to a group of young intellectuals who, deeply attached to the tradition of independence and having no illusions about the nature of the authorities imposed on Poland in 1945, decided not to get involved in the armed struggle against the communists and to try to live and function normally in the post-war reality. Only without compromising their beliefs or faith.

Such attempts usually proved to be on a collision course with the authorities as in the period 1948–1955 any independence of thought was frowned upon. Najder himself was suspended as a student for writing articles for Przegląd Powszechny, a low-circulation monthly published by the Jesuits.

After the breakthrough of 1956, the possibility of a brief scholarship stay in Great Britain came on with the wave of liberalisation. Najder decided to make the trip, interested in researching the works of Joseph Conrad. He managed to get in touch with the writer’s sons. As a result, the bursary stay of several months turned into a doctorate at Oxford and a two-volume biography of Conrad, which is still considered to be an exemplary work that basically exhausts the subject. It was then, however, that it turned out how extremely difficult it was to function without compromises in communist-ruled Poland. Knowing how crucial it was for Najder to receive a passport (which was entirely at the discretion of the authorities), the Security Service managed to persuade him to ‘commit to cooperate’. He never took it seriously, but that declaration itself left him with a guilty conscience for years and after it was revealed much later, already in free Poland, served as a convenient accusation in the hands of his political opponents.

In the meantime, however, the time had come for more serious commitments. In the mid-1970s, because of relative political liberalisation – but also growing frustration in the face of repression, censorship and economic stagnation – several Warsaw-based intellectuals decided to set up the Polish Independence Alliance. Two facts are worth emphasising in this context: firstly, the Alliance was not meant to be an illegal party or – even less so – an underground organisation. Its creators, among whom was Zdzisław Najder, aimed at working out programme proposals as well as unhindered reflection on the situation of the country and ways of remedying it. The name they adopted was equally important. Bombast is a common illness of clandestine operators. The conspirators often use such names as ‘Secret Army’ even if their actual strength is at most equal to that of a platoon. In the case of the Alliance, it was completely different. Mature men, at the height of their careers, reached for the word ‘Independence’ not out of a desire to wield any weapons but with the intention of outlining the horizon of their political expectations. Independence, i.e. sovereignty, was to be a consciously defined and the most important objective, even if extremely remote in 1976.

That choice meant, of course, Najder’s involvement in the Solidarity movement in 1980–1981, with all the awareness of how fragile and non-consolidated the area of freedom thus gained was. When on 13 December 1981 General Jaruzelski imposed martial law in Poland and quashed the independent trade union movement, Zdzisław Najder was in Great Britain, writing the last sentences of his monumental biography of Conrad. A certain chapter of his life was coming to an end: he decided to start another one, accepting the offer to head the Polish section of Radio Free Europe. An independent radio station was much needed by the Poles under the rigours of martial law and drastically tightened censorship, but Najder’s move was also exceptionally brave. The two previous directors of RFE, Jan Nowak-Jeziorański and Zygmunt Michałowski, had assumed the post living in exile since the war. The new director, however, took up the job while formally being a citizen of the Polish People’s Republic. Hence the reaction of the authorities: Najder received an unfounded in-absentia sentence handed down by a military court for his alleged ‘spying for the USA’, absurd even for the prosecutor’s office pushing for it.

Najder returned to Poland at the turn of the decades. For several more years, he actively participated in Polish political life. At that time, he was an advisor to President Lech Wałęsa, Prime Minister Jan Olszewski and two chairs of the European Integration Committee. He also remained faithful to his earlier passions – it was thanks to his support that the Joseph Conrad (Józef Korzeniowski) Museum was established in the town of his birth, now Ukrainian Berdychiv.

In recent years, however, he devoted most of his attention to the understanding of the past by subsequent generations, to maintaining the continuity of collective memory after the cataclysms of war and post-war times. He became first the originator and later the coordinator of a monumental research project. Titled ‘Nodes of Memory in Independent Poland’, it was intended as something like Pierre Nora’s Les Lieux de Mémoire: a catalogue of values, notions and places summing up the tradition of the independent Poland, venerated in the Second Polish Republic, condemned to oblivion in Poland under communist rule. It is no coincidence that the same adjective was used in the project’s title and the political movement created by Najder in the 1970s. It was not by chance, either – I believe – that the thousand-page-long work of over a hundred Polish historians of three generations was published (in 2014) by none other than the Polish History Museum.

Author: Wojciech Stanisławski

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki