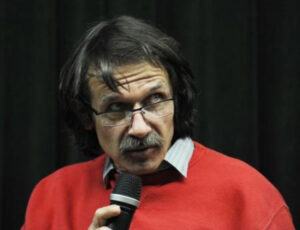

‘Undoubtedly, this revolution shaped a different type of Pole. The one who already spoke their own language and was able to fight for workers’ rights’ says Wacław Holewiński about the 1905 revolution in Poland.

Mateusz Balcerkiewicz: History plays an important role in your work. Would you say you are a historical writer?

Wacław Holewiński: I might have trouble answering this question. History has always been my passion. On the other hand, I believe that from an early age I knew that I would write at least one book. In the one about Colonel Tadeusz Danilewicz, which came into being as Lament nad Babilonem (Lament over Babylon) history, literature, and my own family history have merged. Tadeusz Danilewicz was my grandfather’s brother. But it is also probable that, being a witness to modern history, and having been active in opposition since 1977, I must have been influenced by history, thus my later literary activity. I also have, of course, other passions, such as painting, but fortunately they fit into this historical canon.

In history, I go more and more backwards (apart from my first “painters” novel about the outstanding Dutch painter Jacob Jordaens, of course). Before that there was Żołnierze wyklęci (Cursed Soldiers), about the 1905-1907 revolution. Now I am writing a book about Emanuel Szafarczyk, the leader of the Warsaw Daggers [an armed subversive organization created by the Polish underground state] during the January Uprising against Russia in 1863 – which, in my opinion, was the most important Polish uprising.

I must add that having been brought up in the cult of literature, of eminent writers, I had a somewhat devout attitude towards them. Until my sixth book, even being the vice president of the most important organization of Polish writers, the Polish Writers Association, I still did not have the courage to call myself a “writer”.

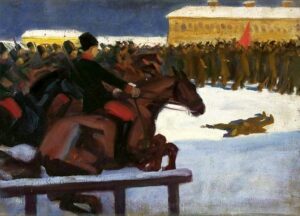

I have the impression that the victory in the Polish-Bolshevik war, whose 100th anniversary we celebrate this year, is a “great absentee” in Poles’ memory of their own history in the 20th century. However, if one thinks about it, even less is talked and remembered about events relating to the 1905-1907 revolution in Poland. When working on the book Pogromy (Pogroms), set in the reality of revolutionary Warsaw, was it your aim to fill in this gap?

The 1905-1907 Revolution is very much forgotten by Poles… You know, one of my grandparents was born in 1895, the other in 1900. I often thought to myself – after all, this is history right at your fingertips, they could have told me the story (in the case of grandfather Holewiński it was impossible – he was killed during the second world war, and the other grandfather, Danilewicz, did not have this type of experience as he grew up on a property far, far to the east). So why do we know so little about this time? The answer seems obvious – these events have been “covered over” by two world wars with millions of victims, the war against the Bolsheviks, and Poland regaining its independence. And I asked myself: would it have been at all possible to regain independence without the fighters from 1905-1907? And each time I realized that it would not have been, as the degree of Russification and denationalization, at least in Congress Poland, was so great that even a dream of limited autonomy seemed unrealistic. We forget that there were no Polish schools, the Polish language could not be spoken in them, that all the signboards had to be bilingual, [and] that in order to make a career one had to enter the Russian state structure, and even better – convert to their religion.

There was one more reason, however, the individual participants. Wonderful, [and] often forgotten today. Who nowadays knows about or remembers Baruch Szulman, a Jewish fighter of the Polish Socialist Party, who featured in songs written during the interwar period? Even the bravest of them, one of the leaders of the Polish Socialist Party Combat Organization, Józef Montwiłł-Mirecki, [who was] executed on the slopes of the Warsaw Citadel, has been forgotten. And the public defender of workers and later minister of foreign affairs, Stanisław Patek or Wanda Krahelska, whose show trial, with its successful ending, brought the tsarist and Austrian legal systems into conflict? They all deserve monuments. Or [even] such figures as the Russian General Andrei Margrafski. Was he really an enemy of the Poles? Although as the commander of the secret political police he had to die… And such dilemmas which Piłsudski also faced: should we confront the authorities, shoot or should we only organize ourselves, train, and be ready?

What was happening then in the Kingdom of Poland under Russian rule?

The Kingdom of Poland was a relatively small area where rapid industrialization was taking place, and it was an area of the great migration of the rural population to cities. It was where the Lithuanian Jews, also known as the Litvaks – who most often did not assimilate and did not know the Polish language – settled. It was a time of terrible misery for some and great fortune for others. If we called it a time of rebellion, it was mainly a social rebellion, not a national one. But at one point these two currents merged into one. And no doubt this revolution shaped a different type of Pole. One who already spoke his language and was able to fight for his worker’s rights. In other partitions, the revolutionary news spread because those who had organized or had influenced it, often escaped to Galicia to avoid arrest. The Prussian partition is a separate story, and the least compatible with the others.

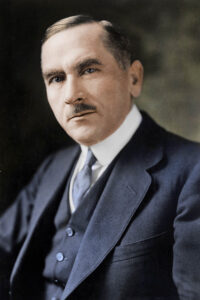

, the hero of your latest book, Oraz wygnani zostali (Thus Were They Banished), is a character from a completely different world than the Polish workers and peasants: an aristocrat, a collector of paintings, a traveller and political writer, and at the same time an eccentric and man of scandals. What fascinated you the most about him?

Everything! The fact that he was such a colorful and ambiguous figure. Keeping his Polish origin at a distance and at the same time creating the greatest collection of Polish paintings. He condemned the uprisings and still wanted to give this collection to the people for free. He funded scholarships for the most outstanding Polish painters, and saved them from hunger. He commissioned specific paintings from them, because after studying painting in Munich, he was deeply familiar with this art form. He was a man with a great breadth of imagination – the owner of an island in the Adriatic, a wonderful yacht bought from Habsburg, and for a whim he bought himself the title of a count in Vatican – he was at the same time a great host, a businessman who skillfully and with great luck invested his money. And at the same time, which is important for the novelist, he was also a scandalous man who [fought] duels, had numerous women, and stood on par with the crowned heads of Europe at that time – free from any complex regarding his birth, wealth or education. And intellectually…? My Lord…

Korwin-Milewski’s greatest merits include his role as a patron of Polish art. What do we owe him?

A collection of probably the most outstanding Polish paintings. In the last quarter of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, Poland gave birth to some extraordinary painting talents: Maksymilian and Aleksander Gierymski, Jan Matejko, Anna Bilińska-Bohdanowiczowa, Franciszek Żmurko, Tadeusz and Zygmunt Ajdukiewicz, Teodor Axentowicz, Jacek Malczewski, Wincenty Wodzinowski, Olga Boznańska Chełmoński, Władysław Czachórski and a dozen others. These are the giants of our art. And all of them, maybe except Matejko (although he bought two of his outstanding paintings), were in Korwin-Milewski’s “stable”, he bought canvases from everyone. He often corrected the composition, suggested changes or simply commissioned a painting on a specific topic.

Unfortunately, the collection has not survived to our time. As I said before, he wanted to give it away for free – first to Krakow and then to Lwow. He had one condition; he wanted these cities to give him a piece of land on which, with his own money, he would build a museum to display the collection. Both cities refused… After regaining independence, he wanted to sell it to the Polish state (he could no longer give it away for free, almost all his huge property remained in the east, outside of Poland) and received a negative answer. The Polish state could not afford to buy it…

Today, we don’t even know all the paintings in this collection. We can identify 70-80 of them. And these are masterpieces! I say a little perversely that we all know these paintings, but almost no one knows that they came from Count Ignacy Korwin-Milewski’s collection.

Korwin-Milewski had very specific political views, which he expressed bluntly, and sometimes offensively. Among other things, he stood in sharp opposition to Roman Dmowski and National Democracy. What future did Milewski see for Poland?

It is very difficult to say. Ignacy Korwin-Milewski was a political adventurer, a man who fought against the entire world, and if he was wrong…the worse for the world. Undoubtedly, rivalry with his younger brother, Hipolit, a member of the Russian Duma, played a part. I do not know if the hero of my novel even considered the possibility of the emergence of the Polish state, he rather saw Poles with some kind of autonomy but within the Russian Empire. He was a citizen of the world, a cosmopolitan. He knew several languages, felt fine in many places in Europe, and changed his citizenship several times. He condemned the Polish uprisings, he was far from Dmowski, and even further from Piłsudski. He was a self-made man, also when it came to politics. And after 1918? He was probably embittered that Poland had left his property to the Bolsheviks, and he no longer lived in Poland, but on his island, Saint Catherine.

The final end of Polish aristocracy came with the arrival of the Red Army and the land reform in Poland at the end of the Second World War. It was described by, among others, Franciszek Starowieyski, a graphic artist, painter and stage designer who came from this milieu. Has anything from the world of Milewski and Starowieyski survived in Poland to this day?

Very little. Perhaps the fact that most Poles look for their roots solely in that gentry past? That it is still impressive? But we forget that that world was a kind of oasis – having a certain Polish quality, patriotism, education and art. As well as good and bad traditions. Today, I think few of us attach any importance to our place of birth. But we still, like our ancestors, have complexes towards the West. But… but Europe has always been here!

Interviewer: Mateusz Balcerkiewicz

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin