In his works discussing the role played by the Poles in the Holocaust, Jan Grabowski fails to utilize some important documents which Communist Poland handed over to West Germany in the 1960s, 70s and 80s. These materials have been recently re-discovered by the Pilecki Institute and considered as essential for providing a more accurate picture of German-Jewish-Polish relations in occupied Poland. The sources reveal how the Nazi terror, purposefully sidelined in the recent scholarship, held sway over Polish countryside and powerfully manifested itself in violent actions against the Jews and the Poles in localities like Węgrów county.

by Hanna Radziejowska

In 1992, a Jewish-American researcher of the Shoah, Raul Hilberg, published the book Perpetrators, Victims, Bystanders: Jewish Catastrophe 1933–1945. It is a vital text for understanding modern Holocaust research. Perpetrators, victims, bystanders – the triumvirate he described became the starting point to label the wartime attitudes of non-Jewish residents of Europe as “observing.”

In the case of Poland, it is used to describe the behavior of Poles towards Jewish escapees who strove to save themselves by taking refuge in forests, villages, and with their neighbors during what have become known as the second and third phases of the Holocaust (the confinement of Jews in ghettos, the liquidation of “Jewish quarters” and the mass murder of Jews in death camps).

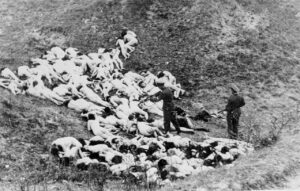

While three million Christian Poles were civilian victims of the terror, another three million Polish Jews murdered, and the state subjected to annihilation in every dimension, Poles have been classified not only as “victims”, but also as “bystanders” in recent academic studies. In some they have subsequently evolved into the role of perpetrators.

In Na posterunku [At the post], Professor Jan Grabowski describes the participation of the Polish Blue Police in the Shoah: “they conducted actions against Jews on their own account, on their own initiative, often out of a peculiarly conceived solidarity with the local populace who asked the Blue Policemen to eliminate the burdensome citizens of Jewish origin – or who may constitute a threat to the village community.”

In contemporary academic discourse, the discussion concerns all three roles of Poles simultaneously: as perpetrators, bystanders and victims.

The German historian Professor Frank Bajohr notes in a volume devoted to Hilberg’s writings (2019) that his triumvirate “cannot fully express the complex and often contradictory social behavior of the actors of those events and the dynamics created by them”, and adds: “If one examines newer research, for example the 2011 book Judenjagd. Polowanie na Żydów 1942–1945. Studium dziejów pewnego powiatu [Judenjagd. Hunting Jews in 1942–1945. A study of a certain county] by Professor Jan Grabowski, one will find cases of individuals saving and killing Jews at the same time.” The analysis of German terror based on these three roles unwittingly became the source of a semantic void in describing the role of Poland and Poles during World War II.

This widely-used description of Poles as perpetrators, victims and bystanders is possible because access to many sources has been limited for decades, and the testimonies of Polish victims – testimonies made to prosecutors in the post-war period – did not enter the canon of international academia.

The team at the Berlin branch of the Pilecki Institute has uncovered in the German Landesarchives another collection of original interrogation documents that were handed over to the Germans in the 1960s, 70s and 80s by the Main Commission for the Investigation of Hitlerite Crimes in Poland. They concern among others German crimes committed against the Jewish and Polish populace in Węgrów and the vicinity in the years 1939–1945. Neither copies nor excerpts of these documents can be found in Polish archives: the prosecutor’s office of the Polish People’s Republic spent many years trying to persuade German law enforcement agencies to act, providing the German prosecutors with full and original court documentation (e.g. interrogations, situational drawings and photographs). These documents were first sent to the Center for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes in Ludwigsburg (established in 1958), and then they were forwarded to individual offices involved in the investigation.

Today, it is the discussion about the course of the terror of the Third Reich in small towns that causes the greatest controversy in Poland and all over the world. The Węgrów county described by Jan Grabowski in 2018 in Dalej jest noc. Losy Żydów w wybranych powiatach okupowanej Polski [Night without End: The Fate of Jews in Selected Counties of Occupied Poland] is a good example of such a discussion. But if we keep the recently discovered collections in mind, it is one that does not take many key archival documents into account.

New documents

None of these testimonies, which made their way to West Germany and remained there, was included in Jan Grabowski’s research on Węgrów county. And they would have necessarily affected his conclusion that “it is irrefutably evident that some residents of Węgrów (as well as of other towns and villages of the Węgrów county) took part in the German extermination activities. Poles from Węgrów denounced Jews to the Ordnungspolizei (i.e. the gendarmerie) and the Polish Blue Police.”

First and foremost these files contain Polish testimonies, but there are also testimonies from Jewish survivors and German gendarmes, soldiers, and SS officers. It is significant that none of the Germans from Węgrów county were brought to trial and none of them were punished.

Jan Grabowski based his conviction that “the peculiarity of the area under study is undoubtedly the participation of a part of the Węgrów community and those in its vicinity in the Germans’ campaign to exterminate [Jews]” primarily on post-war court documents of the Polish People’s Republic. These are testimonies and materials from court files sentencing people – mostly Poles – for collaborating with the Germans in murdering Polish Jews or other Poles. These proceedings were instituted pursuant to the Polish Committee of National Liberation’s decree of 31 August 1944 (the so-called August decree) “concerning the punishment of fascist-Hitlerite criminals guilty of murder and ill-treatment of the civilian population and of prisoners of war, and the punishment of traitors to the Polish Nation”. When discussing these sentences, Grabowski writes in the above-mentioned article about the “tragicomedy” that “took place in the courtroom”, alleging that the courts colluded with the accused to give very low sentences. “The reluctance to settle accounts was not only specific to Poland. A similar refusal to condemn the oppressors of the Jews occurred in France, Belgium, and, more understandably, Germany.”

This singular remark about the German courts, despite Grabowski’s very brief mention of some testimonies of the German functionaries of the terror apparatus, is surprising. The reader of the chapter on the Węgrów district in Dalej jest noc will not learn that literally none of the criminals from Węgrów and the surrounding area he mentions, as well as many others named in the German investigative documents, ever faced trial in Germany despite incriminating testimonies from both Polish and Jewish survivors. All the proceedings in West Germany which concern crimes against Jews and Poles in Węgrów are concluded with a note that the relevant investigation was discontinued, usually due to the difficulty in locating certain individuals or because of “insufficient evidence.”

For instance Karl Tedsen, the chief of military police from the Budziska station in the Węgrów county, responsible for the murder of Jews and Poles, was acquitted of the charges in 1973 due to a “lack of evidence” despite numerous testimonies from Poland. In 1988, during another investigation – following the transfer of another 35 Polish testimonies – Tedsen received a medical certificate stating that he was unable to testify. Prosecutors in Oldenburg noted that “the accused could no longer recall the past events due to his advanced age.”

Rudolf from Sokołów

Kriminalkommissar Rudolf Weber, chief of the 9th company, 3rd Battalion of the 22nd SS-Polizei Regiment and other members of the unit – Uwe Kersten, Gustav Friedrich, Rudolf Diestelhorst, and Anton Kurzreiter (as well as many others) – also testified in the first investigation. Weber himself discusses among others the shooting of 10 Poles in 1942. The company stationed in Sokołów Podlaski took part in crimes committed during the occupation, in Łochów among other locations. The German prosecutors summed up: “A list of members of the 9th Company was drawn up as a result of these proceedings [from 1970 – author’s note]. Under specific circumstances, the list of names could be the starting point for further investigation. Some of the accused were questioned earlier and confessed to shooting civilians. The proceedings were discontinued as qualifying characteristics for murder could not be verified.” Of course, no investigation was resumed on the basis of new materials provided by Poland in the 1980s. Those “specific circumstances” never occurred. Why is this “reluctance to settle accounts” in Germany “more understandable” for Professor Grabowski? How can we then describe Germany’s scandalous lack of punishment for the criminals of Węgrów county?

Grabowski’s text on Węgrów county furthermore gives no attention to the actual scale of punishment for “traitors of the Polish Nation” under the August decree in post-war Poland. By not specifying the penalties received by those collaborating with the Germans, the author denies readers a chance to form their own opinion on this matter.

The post-war “August decree” trial of the Blue Policemen Władysław Królik, Antoni Iwanek, Jan Grajewski and Piotr Grochal for the murder of Jews (the Rubins, husband and wife, and three other people) hiding in the house of Aleksandra Janusz in the Węgrów county is in places controversial for various reasons and certainly requires separate research and discussion. In the trial documentation, we find notes that the interviewees want to change their testimony because they were beaten and tortured by the investigators. The main testimony cited by Professor Grabowski pointing to the guilt of the Polish policemen is one of several versions of this testimony; the one before the forcing of confessions did not give as much clarity as to who exactly performed the killings and was lacking various fragments, e.g. concerning the extortion of money from the homeowner by the policemen. Grabowski himself writes about Królik that although he served with the Polish Police of the General Government, he also collaborated with the Polish underground, and was defended by Jewish survivors after the war. Regardless, the suspects were ultimately sentenced to 15 and 25 years in prison for the murder of Jews.

Another example of the Polish post-war punishment for collaboration with the Germans is the story of Kazimierz Jaworski from the village of Soboń, also described in Grabowski’s article without any mention of the penalty imposed. One night, Jaworski caught a Jew stealing food in his house and escorted him to the village starost, who then took the victim to the gendarmerie station where the Jew was murdered. After the war, Jaworski argued in court that he did not know that the man he had escorted was a Jew and that he did not believe him when he tried to convince him. The court sentenced Jaworski to three years in prison.

If we now return to Hilberg’s “perpetrators, victims, bystanders” and its evolution today, it is easy to perceive a certain logic in the legal consequences which followed. The German criminals are innocent, and the only legally responsible parties for the death of Polish Jews who were hiding and escaping from transports were the Polish collaborators, usually peasants. It is worth posing an important question at this point: were all the collaborators Poles, and did they consider themselves Poles? The role of the Volksdeutscher and the German minority which helped to build the terror apparatus when the Germans invaded Poland – their knowledge of the local community and language was often the main source of intelligence on the situation in villages and towns – is sorely lacking in research on the terror of the German occupation.

One good example of such a problem concerns the sadist and criminal Lucjan Matusiak – a Blue Policeman from the Łochów station – whom Grabowski describes in Dalej jest noc as an excellent example of the process by which the Blue Police “matured” to the murdering of Jews. His cruelty described in the post-war testimonies found in Germany and quoted in the article about Węgrów county makes a deep impression. At the same time, it is worth examining two elements, omitted by or perhaps unknown to the author, which are important for further deliberations. Firstly, we find testimonies in the same post-war investigation that also describe Matusiak’s brutal murders of Poles, including the sadistic abuse of a pregnant woman. One of the testimonies from a Pole beaten and tortured by Matusiak states that he, Matusiak, declared during the interrogation that Poland had finally ceased to exist and that he spoke of himself as a German citizen. In the testimonies uncovered in German Laender archives by the Pilecki Institute, we find two separate testimonies describing Matusiak as a Volksdeutsche, while the German prosecutors themselves searched the archives noting his escape with the German troops in 1944. Is Matusiak an example of involvement in building the terror of the Third Reich by the German minority, the Volksdeutsche, or perhaps an example of Poles who wanted to become Germans, who hated not only Jews, but Poles as well?

Comparing post-war justice in the context of Węgrów and the vicinity, we must note that despite the Communist regime and the indisputable complications of the “August” trials and the persecution of the Polish underground, Poland did much to punish criminals and collaborators, while the German state did not punish anyone, despite the fact that numerous military archives held the records and the data of former soldiers from many various units. As a result, those who punished the criminal acts of collaborators are accused of complicity in the Holocaust on the basis of the court files, while those who implemented terror and enforced the policy of exterminating Jews have become obscured in the background of “Polish collaborators.”

How many Germans were really in the Węgrów county?

In the appendix to his article in Dalej jest noc, Grabowski cites a list of 26 German officers who were supposedly responsible for crimes throughout the entire Węgrów county, and he marks only two posts with German units on the adjoined map. In this way, the reader is given the impression that the entire terror apparatus was made up of the Blue Police and the volunteer fire brigade subordinated to the occupier, as well as the Polish residents.

Meanwhile, the testimonies of German soldiers and officers, made to the German prosecutors in the 1960s and 70s (and contained both in previously known collections and in the newly discovered files from the Laender archives), show that the German gendarmerie in the county consisted of nearly 70 people; there was also a 20-person Sonderdienst unit in Węgrów, as well as the 9th company of the 22nd SS-Polizei Regiment and the Wehrmacht stationed at the ammunition warehouse (HEMULA) in Baczki. A unit of the Ukrainian Hilfspolizei and the staff of the Treblinka camp also took part in the pacifications. Therefore, the terror apparatus in the region involved some 300 people. And the testimonies show that the arrested Poles were taken to the Gestapo post in Ostrów Mazowiecka and that the local military units supported the neighboring counties in individual pacifications. These numbers should also be augmented by the German administration, officials and bureaucratic staff, which were busy with robbery and economic exploitation. Today, the Polish Blue Policemen and the fire brigade remain the only highlighted points on an otherwise blurred map of terror.

It should be noted that, based on the testimonies and accounts of Holocaust survivors at the USC Shoah Foundation, it is difficult to infer that the Blue Police and fire brigades were a principal threat to Jews who went into hiding in the second and third phases of the Holocaust. And yet Jan Grabowski states both in his article about Węgrów county and in his newest book, Na posterunku, that it was precisely in small towns and villages where the Blue Police and fire brigades acted virtually “on their own.” In Na posterunku he estimates that almost 80 percent of arrests of hiding Jews (as a result of which they lost their lives) were brought about by the Blue Policemen.

Out of nearly 40 reports about Węgrów and the surrounding area, however, six Jews reported having received help from firefighters or Blue Policemen, and the Blue Police and fire brigades do not feature at all in the extensive testimony of Cyra Rubinstein, given in the 1960s in Tel Aviv and describing the liquidation of Węgrów on 22 September 1942.

The story of Natan Najman

A good example of the range of problems raised by Grabowski’s thesis is the shocking account in the archives of the Shoah Foundation of Natan Najman, who lived in Budziska near Łochów. As a 9-year-old boy, he survived the hell of the liquidation of the Jewish ghetto in Budziska and the ordeal of being loaded into cattle cars by his German torturers. Having squeezed through a hole in the planks of the train, he began his epic struggle for survival.

There is a section in Najman’s account as cited by Grabowski which coincides with recorded history (which can be accessed through the Shoah Foundation website), namely that he encountered bandits, people who robbed those who had escaped from the transport. At some point, however, the story diverges; in the book Dalej jest noc we read a different version from what Najman says in the recording. We find the story of him meeting a Jewish colleague who is shot at the Blue Police station (having been taken there by Poles), while he himself escapes. Grabowski ends the story about Natan Najman by mentioning that he finally found shelter with Mrs. Stanisława Roguszewska, who was subsequently named Righteous Among the Nations.

In the recording, Najman says that he first spent several months in hiding with other Poles, former neighbors and family friends. Fearing for their lives, they asked him to look for shelter elsewhere, and only then did he run into his friend. Indeed, both of them were taken to the Blue Police station, but there the Polish policeman ordered them to flee at once (“There was probably no one from the gendarmes about – they were out on some kind of excursion. […] The policeman thought for a moment, looked at me – he knew my father, he used to cut wood for them before the war – he waved his hand and said ‘just go to Kosów’”). Najman found shelter with various Polish families; according to his testimony, he spent several months in each place, going through many dramatic and terrible moments of flight, hunger and fear before he made it to Stanisława Roguszewska with whom he hid until the end of the occupation. During its course, he and his siblings found food or shelter in areas where people knew and remembered them.

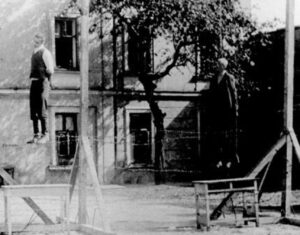

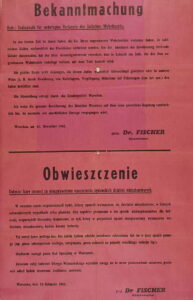

This account shows the role of Polish neighbors during the Holocaust. Yet listening to the shocking story of young Najman, we touch upon another research problem: the intersection of Polish and Jewish testimonies about the occupation at moments of lending aid and giving shelter. The Polish testimonies paint a picture of the incredible terror during the occupation. It is impossible to comprehend it without understanding how the “violent spaces” functioned, to refer to Jörg Baberowski’s excellent book on the shaping of legislation and statehood in Europe through terror, torture and violence (Räume der Gewalt, 2017). The violent space, in this case built and managed by the state apparatus of the Third Reich, was based on the murder of 100,000 members of the Polish intelligentsia and leadership in the first year of the occupation, the planned extermination of Jews, and the punishing with torture and death of all who helped them, as well as on daily terror against Poles, economic exploitation, and robbery. The accounts discovered by the Pilecki Institute in the German archives reveal a picture of the death that loomed every time German gendarmes came to a village. They killed for the mere suspicion of sheltering Jews – Franciszek Subda and his brother-in-law, Wacław Andrzejuk, were murdered in January 1943 by gendarmes from Kosów Lacki. Mieczysława Subda, Franciszek’s daughter, testified that she was beaten up by a German gendarme who, pointing to her little brother who had been doused in petrol and set on fire by another German, yelled at her “where are the Jews?” (The family was not hiding Jews). The Germans murdered Poles for not reporting for forced labor on time, for aiding Jews or Soviet POWs, for not releasing required quotas of food, or simply for no reason at all.

Death for staring

In the testimonies from the state archives, we find examples of one village resident who “stared” at the passing Germans and was shot as a consequence, or of a wife who, asking for permission to bury her husband one day after his execution, learned that he was shot by mistake.

The fear described by Helena Roguska, Righteous Among the Nations, which she experienced when hiding five Jewish friends, does not appear in Grabowski’s text in Dalej jest noc. Neither is there the sentence from Sara Kaye’s testimony from the Shoah Foundation which mentions that “you could never stay with anyone for too long because they could all be murdered.” Similarly there is no mention about Helen Kaminsky, who found shelter with a single mother with several children, and who left in order not to expose the Polish family to the danger of death. In his article about Węgrów, Grabowski similarly fails to quote another survivor, Gloria Glanz Przepiórka, who talks about the posters notifying that helping Jews was punishable by death. As a girl, Gloria was handed over by her parents from Węgrów to their Polish friends in the countryside. Those Polish peasants protected her and even tried to maintain Jewish customs for her.

The Holocaust survivors who knew the Polish realities better and who had a closer bond with the Polish families with whom they were hiding recalled the terror against Poles as a reference point for the price of the aid provided. However, it must be remembered that the experience of unimaginable humiliation and the struggle to survive despite receiving help from various Poles often left only bitter memories for the survivors. Halina Wachtel recalled when she “knew nothing about the world, only where we were and nothing more. I felt abandoned by the whole world.” Minia Lederman remembered her bitterness at seeing the contempt and wickedness of the Poles she encountered, saying: “They were worse than the Germans – they did it of their own free will.” Grabowski describes these memories of Jewish survivors as follows: “Looking at the issue of saving Jews from a more general perspective, it can be assumed that the chances of survival for the hidden Jews were determined not so much by the help of their neighbors, but simply by the lack of ill will toward them.”

Could these two realities – the Polish and the Jewish – eternally distant from one another, have been reconciled? This division, consciously and deliberately carried out by the German terror, and sustained by the Iron Curtain after the war and by the resulting lack of access to Polish testimonies and knowledge of Poland’s fate during the occupation, has always robbed Jewish survivors around the world of the full context in which to situate their trauma. They did not learn that, apart from the terrible meanness they experienced, the dislike they were sometimes shown was likely fear and terror and helplessness, and not contempt. Even more important was the fact that the real perpetrators – the functionaries of the Third Reich – were not punished in Germany after the war.

A fair trial in Germany would reveal the testimonies and bifurcate the perception of perpetrators and victims. After all, there is not a word in any German testimony from prosecution investigations in the state archives that the crimes were committed by Polish policemen or firefighters, and it is difficult to imagine that, if this was really the case, the German officers would not have used the chance to clear themselves of the charges. The triumvirate in which Poles have become, at best, victims, but most commonly bystanders and perpetrators, is the result of a lack of reliable research on the price of helping Jews. Most of the survivors who met Poles who helped them in any form experienced not only “ordinary human kindness” and compassion, but most of all great courage and heroism. Therefore, work on documenting and commemorating Poles murdered for saving Jews is not a manifestation of Polish nationalism, but a campaign to restore true points of reference to the reality of the Holocaust and to build a network of concepts that also describe the tragedy of the Polish experience.

The Polish version of this essay, entitled “Czego Grabowski nie napisał..” was published on 17.10.2020 in the newspaper “Dziennik. Gazeta Prawna”.

The English version has been published on the website of the Pilecki Institute’s Berlin branch.

Hanna Radziejowska heads the Pilecki Institute’s Berlin branch since 2019. She is a historian, a cultural manager, as well as a descendant of Holocaust survivor.