The Polish manor house in the 19th century was no longer a simple “architectural project”. Those who owned manor houses were aware of the past and the meanings behind the architectural solutions and thus treated them both as a living space and an investment, e.g. as a “value carrier”. This was especially important during the partitions, when the land-owning elite faced the pressures of denationalization.

by Maciej Rydel

We talk about a one-story manor that belonged to a landowner, not about a sumptuous aristocrat’s palace. The manor house changed over the centuries, but Poles are especially sentimental about the classicist one-story manor house with a columned porch, located somewhere in central Poland or in the eastern part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. It is worth combining two threads for understanding the manor: the architectural and aesthetic with the social and moral. Along with its foundation in tradition and custom, the creation of a landowner’s seat was justified by the specific needs of its owner.

The manor house was usually located on a hill. Sometimes it even stood in the place of an older manor from the 16th century from which only the cellar survived. The family seat usually faced the main road along which there was a tree-lined alley, most often linden, chestnut or hornbeam. The manor was situated towards the sun that illuminated it from four sides throughout the day.

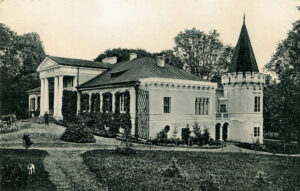

There could not, of course, be a manor without a park. One would assume a specific mood when crossing the gate and entering the shaded alley which led to the manor. (photo 2). Sometimes parade gates were built, and the owner’s coat of arms was visible above the entrance. We can see the same coat of arms above the entrance to the manor house.

Directly in front of this entrance was a lawn, either oval or round, which was sometimes surrounded by a hedge with a flower bed in the center (photo 3). This created the cour d’honneur, a courtyard of honor, that was almost obligatory in the 19th-century as a symbol of the prestige and dignity of the landowner’s place of residence (photo 4).

A brick white manor house

A classicist building was usually painted white (never blue – the color of peasant cottages). The four-column portico, extending beyond one interior story, determined the so-called colossal architectural order.

Three elements are characteristic of the architecture of the manor house: firstly, the plan, and secondly, the shape of the body (including the extremely important proportions of the height of the walls to the height of the roof). The third element is the aesthetics of the centrally placed entrance. Associations of the Polish manor with a columned portico, so popular today, applies to buildings erected in the Classicist style, starting from the last quarter of the 18th century. Classicism in Poland had dominated the architecture of churches and palaces quite early; it arrived at the manors following a delay of at least twenty years.

Let us take a closer look at the portico, an essential attribute of the Classicist manor. There are many types of porticos: we know the so-called “regular / small order” (photo 3) or the “colossal order” (see Tułowice and Tarnogóra). Porticos had two, four, six or eight columns in the Doric, Tuscan, Ionian and Corinthian orders. The eight-column Ionic portico, can be seen in Konstantynów (photo 5). The most popular is the Tuscan order (see Fig. 3, 4, 18). In modest mansions of the parochial nobility, the portico, and earlier a wooden porch (photo 6), was often the most basic element which indicated the noble status of the owner. Today’s image of the wealth and splendor of the manors is definitely exaggerated.

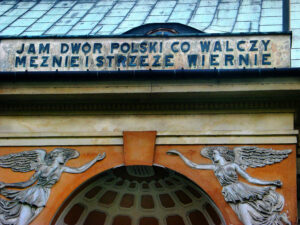

The architrave rests on the column heads. In the tympanum there are either windows, most often in the shape of a circle or a semicircle or bas-reliefs depicting the cartouche of the owner’s coat of arms (photo 7). Inscriptions are rarely found, only a few sentences or the year of the construction of the manor. Above the entrance to the manor in Pęcice (Masovia region) there is a characteristic inscription: “I am a Polish manor, which fights bravely and protects faithfully” (photo 8). In Wola Pękoszewska near Skierniewice, on the front of the manor house, under the two coats of arms of the spouses Antoni Górski and Anna née Szembek, there is a fragment from Jan Kochanowski’s epic poem: “Let me, Lord, live in this home nest, and give me health and pure conscience.” This inscription was quite popular and appeared at many courts.

Now let’s look at the roof of the manor house. The so-called “Polish roofs,” were used from the 17th century. Unlike the mansard roof, the upper and lower two sides of the Polish roof are parallel to each other, which can be seen in illustrations no. 1 and 6. The archers, which also attract the visitors’ attention, are a remnant of knightly times. Then the defensive turrets, later miniaturized, no longer served a defensive function only a residential one (see Fig. 1).

And inside? The hallway had its own specific atmosphere. Sometimes it was decorated with antlers of hunted game (photo 9), and large wardrobes for outer clothes. Sometimes a harvest wreath hung in the center of the hall. Harvest Festival was held on the feast of Our Lady of Herbs, 15th August, when the end of the harvest work was celebrated. On this occasion, a wreath was made of the finest ears of grain, flowers, and fruit, decorated with ribbons and blessed in the church and carried to the court, where it was handed to the heir. The wreath usually hung until the following summer, creating a feeling of being bound to the land which sustained those living there. Sometimes there were also old chests, which only played an auxiliary role in the 19th century, once wardrobes came into common use.

From the hall to the living-room (salon)

As a rule, hosts invited their guests to the living room (photo 10). There they would encounter the children and other household members, usually many generations lived together: grandparents, aunts, and resident uncles. As a rule, the manor was multigenerational (photo 11).

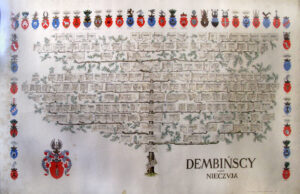

The living room, apart from a large ornate stove, sofas and armchairs, housed a piano, and the walls were decorated with paintings, a characteristic element of every manor. Usually, one would not see the great masters of Italy or France, instead graphics, etchings and drawings, as well as oil portraits of ancestors, dominated. Sometimes these were the works of itinerant painters, who walked from manor to manor where they were offered board and lodging for painting genre scenes, landscapes and portraits of household members. A characteristic feature of the manor house was the accumulation of souvenirs, equipment and furniture from different eras. It was rare for a manor house owner to buy new furniture in one go. In many manors, as in Tułowice, for example, there was a panoply on the wall (photo 12). On the rug there are national symbols, the gorget of the ancestor-knight with Our Lady of Częstochowa, and under it, crossed sabers and old parts of armor. These traditions were also passed from generations. There were family trees created, usually rolled up in drawers, or sometimes hanging on the wall of the manor house (photo 13).

Since we have mentioned the painters traveling from manor to manor and offering their artistic services, it is worth mentioning one well-known name: Bronisława Rychter-Janowska. She was able to present the atmosphere of the Polish manor like no other. Her work related to Polish manors dates back to the end of the 19th century and up to the 1940s. Today she is called “the painter of Polish manors” because she knew them very well and lived in many of them. On commission, she painted landed estates, romantic interiors, and romantic scenes from the life of the manors (photo 14). Following the release in the 1930s of a large series of postcards with reproductions of her paintings, Bronisława Rychter-Janowska became a very popular painter in the period leading up to the Second World War. It was popular to send these postcards en masse at Christmas and Easter (see Fig. 24).

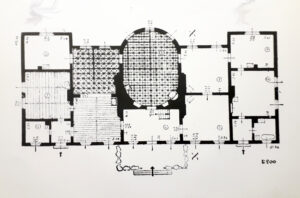

Let’s go back to the 19th-century manor. The layout of the rooms inside our manor house is two-bay, with a hall and an oval living room on the axis, protruding in front of the garden façade (photo 15). The rooms are situated in the so-called enfilade, i.e. they are all connected from the first one till the last one. The dining room was accessed by the hosts and their guests from the living room when the table was already laid (photo 16). Since hierarchy was strictly followed in the manors, there were usually two tables. One in the dining room, the so-called the first table at which the household members sat – the residents of the manor and their guests. The second table was in the outbuilding and people from outside the family ate there, e.g. administrators, teachers, servants.

Meals were brought into the dining room from the butler’s pantry, where the food was usually put into suitable dishes. There was a huge cupboard in which all the tableware, cutlery and tablecloths were kept. Even in the early 19th century, kitchens were located only in the outbuildings and throughout the year, even in the coldest winters, food was brought from the outbuilding to the butler’s pantry. It was only in the first half of the century that kitchens began to be included in the layout of the manor, placed either in the part added to the old manor house, or in larger manors – in the basement. It was not until the end of the 19th century that the kitchen gained the full right to be present in the manor.

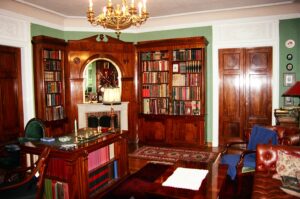

After lunch, the host invited guests to his office, where he discussed current affairs with the steward, receiving his reports and giving orders. Here, he kept the most important agricultural documents and calendars, full of advice and recommendations for modern agricultural and economic matters. Apart from paintings, the walls were decorated with hunting trophies. Some offices also functioned as a library (photo 17). The room would feature a fireplace and library cabinets, from floor to ceiling, adjusted by a local carpenter. The library would contain agricultural guides, books by Polish, French and German writers, albums with drawings of animals, herbs, flowers, and notebooks with devotional and patriotic songs.

Yellow and salmon rooms

To complete the image of the manor, let’s list those rooms to which we would most likely not be invited: bedrooms, possibly with an alcove, i.e. a recess with a bed, moreover, the children’s rooms or the grandparents ‘and residents’ rooms, and finally rooms for guests. It was a common practice to name rooms after the color of the wallpaper on the walls. So there were “salmon”, “blue” and “yellow” rooms. In total, there were about 12 rooms in a medium-sized manor with an area of 400 m². To this you should also add a small room, the so-called Still Room, where not only medicines and herbs, but also home-made preserves, liquors, candles and other basic items were stored. Until the mid-19th century, most often there was no separate bathroom or toilet in the manor. People would wash themselves in the bedroom, where there were appropriate equipment behind the screen. In large manors, in addition to the rooms mentioned above, there were chapels, smoking rooms and billiard rooms. There were also the so-called “School rooms”, as the children received their first-grade education at home.

The manor house, by definition, was one-story, in some cases it had a residential part in the attic. Usually there were, additional 2-3 guest rooms or bedrooms (see Fig. 4 Tułowice and 18. Tarnogóra). Sometimes huge attics were a storehouse of unnecessary stuff, various trunks and suitcases, old furniture and a kingdom for children’s winter play.

A characteristic feature of Polish manors was their expansion. In the 19th century, a small turret was added, already then serving as additional rooms, e.g. guest rooms. The mansions often turned out to be too small for the owner’s needs and sometimes a multi-storey part was added to them. In the second half of the 19th century, some manors were enlarged, in line with the neo-Gothic style, with new parts in this style (photo 5 and 18).

Nannies and teachers

The group of household members in the average Polish court also included the often very well-developed “pedagogical forces”: nannies looking after young children and tutors after the older. Since the first lessons were learned at home, teachers were hired to teach children more than just writing, reading and simple arithmetics. After graduation, many young noblemen earned their living as teachers in landed gentry families. The canons of court life included teaching children, apart from the school curriculum, to draw and play some musical instrument, most often the piano. Many famous Polish painters were employed as drawing teachers of landed gentry children and thus earned their living.

Paradoxically, the history of Poland was strongly influenced by an episode of Tadeusz Kościuszko’s life. As a young man, he taught drawing to the daughters of his father’s friend Józef Sosnowski. He especially focused on Ludwika and was so zealous in his teaching that he fell in love with her, approached her father, at that time a Smolensk voivode and Lithuanian field hetman – for his daughter’s hand. Unfortunately, he was not accepted. It was 1775 and afterwards Kościuszko left for America to become a general of the American army in 1783.

The upbringing of landed gentry children was marked by austerity, full obedience to their parents, grandparents and respect for the elderly. The essential canons of upbringing were the worship of ancestors, attachment to tradition and “civic” thinking, which was primarily intended to teach responsibility.

It must be remembered that family traditions and attachment to the land of their ancestors were of great importance in raising children. There were places where the same families continued for several centuries in the same estate. This was the case, for example, in Skotniki near Sandomierz, which belonged to the Skotnicki family continuously from at least the 13th century to 1945 (photo 19). The surname of this family comes from the name of the village. The manors were natural museums because their interiors contained old furniture, paintings, porcelain and ancestral silver, and sometimes collections collected by their ancestors. The libraries contained the archives of the family and the area, correspondence with neighbors, offices and sometimes even royal courts.

* * *

After tasting home-made vodka, honey or liquor, the ladies stayed at home for gossip, and the gentlemen went to see the farm – the pride of the house owner – a horse stable connected with a coach house, a cowshed, sometimes even for up to 120 cows, a brewery where beer was brewed, and a granary with fine grain, freshly threshed in the barn.

The manors were primarily an economic center. The acreage of land at one manor house in a small farm was up to 200 hectares, on average from 200 to 1,000 hectares (the largest number of such farms) and over a thousand in large farms. Forests were usually part of the property. The average size of the property in 19th-century Poland was approximately 400 hectares.

Władysław Łoziński, the author of the book Życie polskie w dawnych wiekach (Polish Life in Old Times), published in Lwów in 1907, wrote: “The most significant feature of the manor house is the universality and self-existence of its entire being, due to the nature of times and things. It was an organism closed in on itself and within itself, a state on its own accord. In order for life to be bearable in it, it had to be independent of the outside world as much as possible, sufficient for itself. Everything was done at home. (…) In every manor house, hard alcohol was made, as well as various liqueurs, and home-made beer was brewed. The table was supplied on the spot; what the forest, the field, the garden, the cowshed did not give you, you did not eat. At home, they made honey, pressed waxes, dried meat and fish, made medicines, and even manufactured ink.”

In the outbuilding there were guest rooms, apartments for the teacher, manager and the housekeeper. There was also a laundry in the outbuilding. Such a very modest outbuilding was the building at the Skarbek manor in Żelazowa Wola, where Mikołaj Chopin, a teacher of French language and literature, found shelter. It was in such an outbuilding (which later, in the 1920s, expanded to the size of a manor for museum purposes), that the genius of Frederic was born.

There were not that many service staff in the average Polish manor. Of course, a lot depended on the wealth of the owners and the number of people living in the manor. The basic staff consisted of a cook, a maid of a housewife and a host, a nanny for the children, and when they grew up, a home teacher. The steward ruled the farm, the coachman and his assistant took care of the horses. In larger, very wealthy manors and palaces there were housekeepers, butlers headed by a “majordomo”, gardeners, dresser boys, forester, and blacksmiths, etc.

The recipe for the nut cake taken from the notes of one great-grandmother begins this way: “Sit the kitchen maids, let them peel the nuts while singing.” The idea was to keep them from eating nuts, so this singing became an obvious part of the recipe.

Near the outbuilding there was a cold storage: a straw dugout, where several layers of ice cut from the pond in winter, kept the temperature low until the next winter, and where meat wrapped in white linen could be safely stored for a long time, without fear of spoilage.

In the depths of the park there was usually a chapel, a small symbolic one (see watercolor – “symbol of duration” – Fig. 1) or a large family chapel, where services were held on Sundays and holidays. These chapels had tombs in the basement where deceased family members were buried (photo 20).

Among beeches and plane trees

The manor parks (photo 21) had from one hectare to several hectares, sometimes turning into the forest (photo 22). The park surrounding the manor is simply an element of the surrounding nature. Entering the manor house into the surrounding landscape was an obvious imperative for the owners. Thus, the landowner simultaneously took advantage of the benefits offered by the nature landscape that surrounded his manor and naturally shaped this landscape in accordance with the principle “surround yourself with natural beauty and multiply it”.

The pride of the park and the pride of the owner were old, many branched trees, most often oaks, plane trees, chestnuts, linden trees, and beeches. Parks were sometimes older than manors, especially when a new manor was built in the place of the old one. The park provided shelter from the winds because it must be remembered that in the medieval tradition, manors were built on hills for their better defense. And on the hills and mounds, the winds might be annoying. The park provided prestige, as did the gate, the courtyard, steps to the manor, and the lavish portico. Finally, the park deepened the aesthetics of the seat. Most often it was made of native plants, but some also imported exotic trees that diversified the variety of the trees. The so-called “English” landscape park, formed in the 19th century, had four levels: grasses, flowers, shrubs and trees, and appropriate, free compositions created wonderful “prospects”. Pergolas, fountains, garden sculptures, artificial hills, not to mention seasonal flower arrangements, appeared as elements of the garden.

One should not forget about the vegetable garden and the orchard, which were an important part of the farm and also ensured the self-sufficiency of the manor house as discussed above. A pond was also an essential element in the park at least the kind that offered both recreational and economic functions. Here the host kept fish, and not only for the Christmas Eve table. There is a gazebo over the pond, standing slightly to the side so as not to obstruct the beautiful view (photo 23).

The manor owner boasted of his great Arabian horse, bred by Count Juliusz Dzieduszycki, purchased in Jarczowce in Podolia. Many landowners’ estates were famous for their magnificent Arabian horse studs. Polish breeding was known all over Europe at that time. Count Dzieduszycki’s stud farm in Jarczowce (today’s Ukraine) was moved to Jezupol at the end of the 19th century, and in 1920 it became the basis of the state Arabian horse stud in Janów Podlaski.

Meanwhile, in the aforementioned gazebo, the spouse of the owner waited for her guests further on, ordering the setting of the table standing there.

See also: The Polish manor house – A symbol of tradition

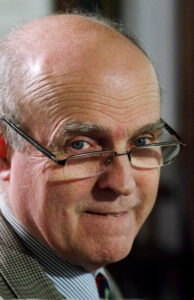

Author: Dr Maciej Rydel

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin

Watercolours no: 1, 2. – Maciej Rydel; Photographs no: 3, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12. 13, 16, 17, 20, 22, 23 – Maciej Rydel; Illustrations no: 6, 14, 15, 18, 19, 24 – archives of Maciej Rydel; Illustration no: 4. Andrzej Novák-Zempliński; Illustrations no: 9, 13 – National Museum in Gdansk, Department in Waplewo Wielkie; Illustrations no: 21 – Lusławice Opus, Słowo/obraz/terytoria, Gdansk 2000, watercolour: Dorota Pancerz-Łyskawińska. All rights reserved.

Dr Maciej Rydel – Documentalist of Polish manors and the history of the gentry. Author of 5 books on that subject. Author of over 150 articles and lectures on the Polish gentry. Author of 20 photo exhibitions (including in Brussels, Jaszuny, Lithuania and participation in an exhibition in London). Painter-documentalist. Vice President of the Main Board of the Polish Landowners’ Association, Vice-president of the Gdańsk Branch of the Association of Art Historians. He was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta (2014) for his contribution to the national heritage.