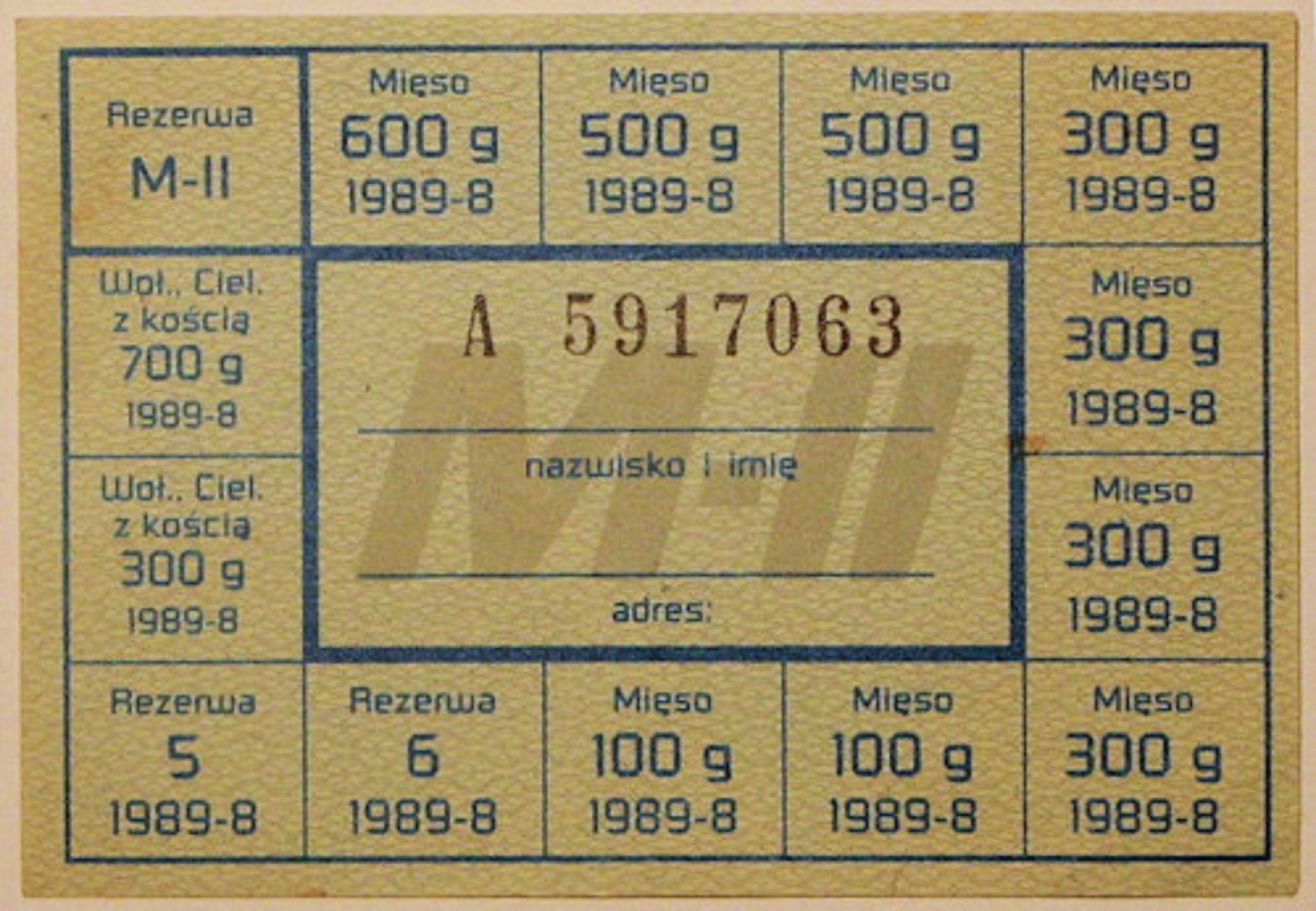

Poland in the 1980s was a country ruled by a military-communist junta. A country where militia officers were unpunished and no citizen could feel safe.

by Grzegorz Wołk

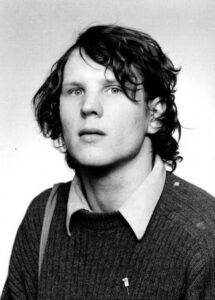

Castle Square in Warsaw was a place where young people often met in the spring and summer, especially during final secondary school examinations. They met for dates there, talked about difficult exams, their plans for life and dreams. Dreams that high school students living in communist Poland also had. Grzegorz Przemyk was one of thousands of such dreamers, a sensitive boy and promising poet. He was brought up by his opposition-linked mother in an ‘open’ home, which was frequented by many interesting people: writers, journalists, and activists of the underground Solidarity movement. His beating by militia officers at the notorious police station located on Jezuicka Street was the beginning of a tragedy that outraged thousands, and the drama did not end with the young man’s death.

A fatal high school graduation

On 12 May 1983, as every year at this time, numerous groups of youngsters could be seen at Castle Square. Boys in white shirts and suits, and girls in equally elegant outfits, neatly ironed skirts or dresses. All cheerful, which was hardly surprising. They had just passed their final secondary school exams and were enjoying one of the most important moments of their lives. In a month’s time, other exams awaited them – to obtain a place at university… You could hear laughter, loud conversations, as well as the occasional clink of a beer or wine bottle.

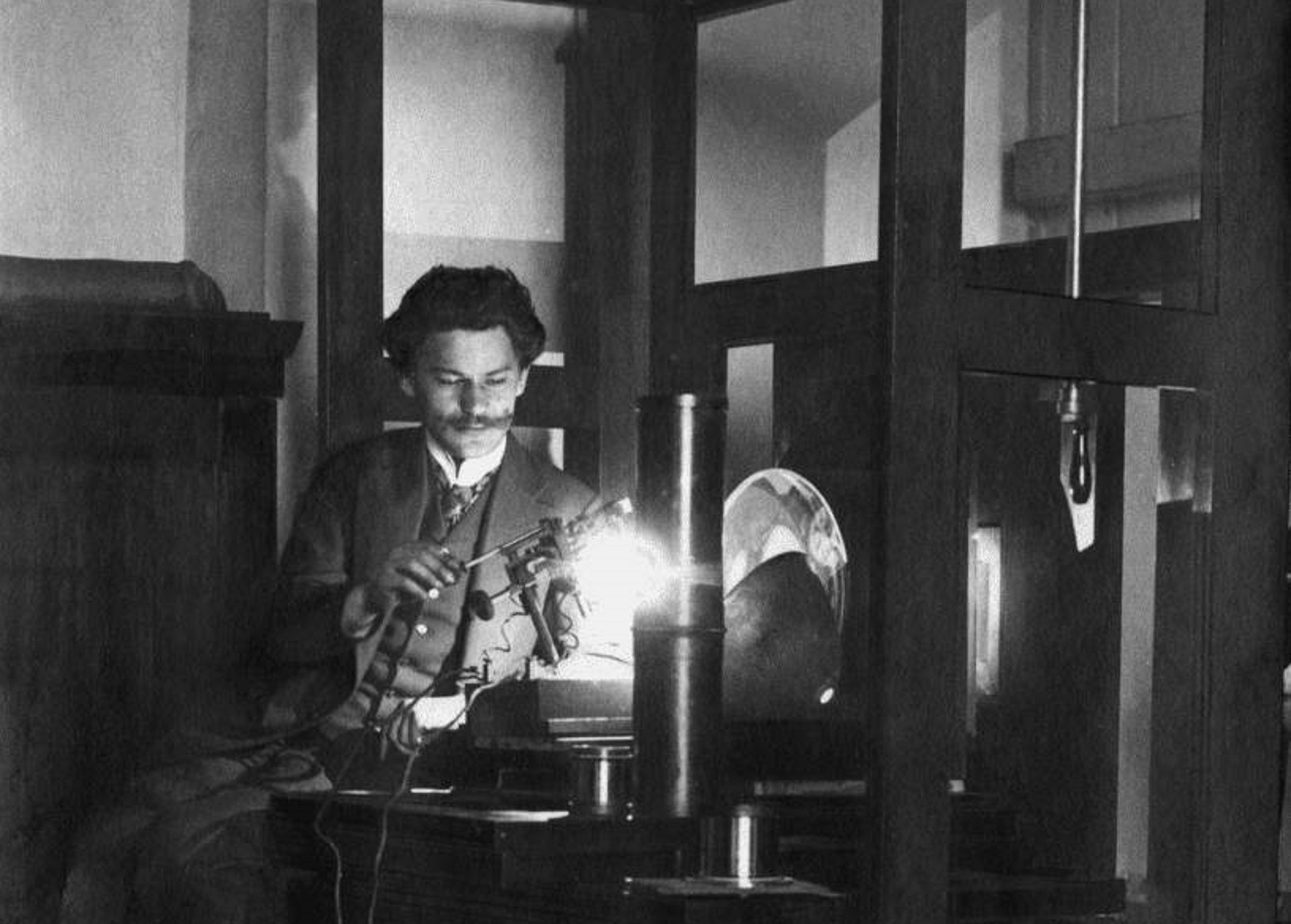

Grzegorz Przemyk was there too. He did not stand out among his peers – perhaps apart from his long, somewhat hippie-like hairstyle, nothing special really. At least at first glance. With their loud behaviour, he and his friends had attracted the attention of militiamen patrolling the historic centre of Warsaw. It was a situation like thousands of others on sunny days in city centres. However, in communist Poland, this particular intervention would turn into a tragedy.

The intervening militiamen dragged two adolescents, who did not manage to escape, to the nearby police station on Jezuicka Street. In communist Poland, this did not mean anything good. Often abusing their power, the militia did not enjoy the trust of the public. In addition, its officers were often poorly educated, which was the subject of jokes on the one hand, and the source of their brutality on the other. Following the imposition of martial law in December 1981, consent to militia violence increased even further. It was not only activists from the Solidarity underground who felt threatened by it, but also ordinary citizens. A few days before the detainment of Grzegorz Przemyk, his mother, Barbara Sadowska, was beaten up. She was a member of the Primate’s Committee for Aid to Persons Deprived of Liberty and their Families. Dressed in civilian attire, militiamen from a special formation ironically called an ‘anti-terrorist unit’, demolished the Committee’s premises, destroying, among others, supplies of medicines that were difficult to obtain in the Polish People’s Republic, and beat the people present there. They also kidnapped and threatened to kill six of the Committee members. It is therefore not surprising that, when Sadowska’s son was beaten, it was suspected in opposition circles that he had not been an accidental victim. Especially since the poet, harassed by the secret police, had been threatened that something bad might happen to her son. The intimidation was not without reason: fear for her child was intended to exclude Przemyk’s mother from public activity.

However, the militiamen from Jezuicka Street almost certainly were not acting according to a predetermined plan. Had the communist Security Service (Polish acronym: SB) actually been behind the fatal beating of Grzegorz, the operation would have been prepared in a more professional manner. Beaten – according to one of the militiamen – ‘in such a way as to leave no traces’, Przemyk died after two days of agony, the cause being multiple internal injuries. Neither the paramedics from the ambulance that was called nor the doctors from the hospital to which he was taken, were able to help him.

Despite the years that have passed, questions about the behaviour of the police towards the victim have never been clearly answered. Did they know who they were beating? Why were they so brutal with the young man who, according to outsiders, had not shown them any aggression? These are just a few of the puzzles. The chances of resolving the doubts unequivocally years later are slim.

A funeral that gave hope

Przemyk’s funeral turned into a huge silent demonstration against the brutality of the communist authorities. Several months earlier, General Jaruzelski, defending his own power, had decided to smash the multi-million-strong Solidarity movement with a military coup. The communists had been brutal. Tanks were stationed in the streets, protesting workers were shot at, there were fatalities and thousands of people were imprisoned. There would likely have been more victims had Solidarity, which was reconstructing itself underground, decided to respond with violence. It did not, and perhaps it was thanks to this that riots did not break out in the country following the news that an under-19-year-old boy had been beaten to death at a militia station.

Father Jerzy Popiełuszko had also had a great influence on the peaceful course of the funeral ceremony. During martial law, this Solidarity chaplain was famous for his holy masses for the Homeland gathering thousands of worshippers, as well as his uncompromising sermons stressing the value of ethics and dignity, which the communists perceived as an attack on the authorities. Popiełuszko was therefore ruthlessly fought against by communist propaganda, and a year later SB functionaries kidnapped and brutally murdered him.

At Przemyk’s funeral, however, Father Popiełuszko had called for calm. It was to his credit that the funeral procession of several dozen thousand people walked peacefully for several kilometres through the streets of Warsaw until it reached the Powązki Cemetery. The march was a silent cry of social protest against the brutality of the authorities, and the first one so well-attended since the introduction of martial law. Despite the fact that the true causes of Grzegorz Przemyk’s death were known not only to the participants of the funeral ceremony, the communist authorities decided to spectacularly deny the most obvious facts. To achieve this, they had had no reluctance to break apart the lives of more people still.

The Kiszczak doctrine

In the Przemyk case, apart from the death of the young man, what was particularly galling was the use of state machinery to cover up the crime and defend the true perpetrators. Orders in this case came from the very top. In June of 1983, a month after Grzegorz’s death, General Czesław Kiszczak, head of the Ministry of the Interior at the time, and one of General Wojciech Jaruzelski’s closest collaborators, clearly explained to his subordinates that ‘officers who, participating in the struggle to maintain order, were forced to abuse their power and are accused for this reason, must be ruthlessly and consistently defended. For we did not provoke social tensions and riots. Cases of this type must be treated as actions during a struggle, for which an officer cannot face unpleasant consequences.’ Understood in this way, Kiszczak’s doctrine was clear: no representative of the communist government, as long as he or she is on the side of the system, will face consequences if applying excessive violence.

A month later, Kiszczak referred to the death of the secondary school graduate during a meeting of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. The brutality and incompetence of ordinary militiamen had led to a crisis, the solution of which was dealt with by the most important people in the state. As head of the Ministry of the Interior, Kiszczak was adamant and pushed for a tough stance aimed at acquitting the perpetrators. During the meeting, the prevailing approach was: ‘end and explain it quickly’. This ‘clarification’ in the communists’ actions consisted in finding culprits outside of the Ministry. The entire state machinery was harnessed to create a false version of the events. The investigation was aimed at cutting off all traces leading to the militiamen from the Jezuicka Street station. An alternative version of the death was also developed, immediately picked up by official propaganda. The only people deemed responsible were the very ones who had helped the boy beaten by the police.

Judging the innocent

In one of the memos drawn up at the Ministry of the Interior, discovered in the SB archives years after the tragedy, was a handwritten note by General Kiszczak himself: ‘There is to be only one version of the investigation – the paramedics’. The investigators strictly followed the orders of the head of the Ministry. They made it difficult to identify the militiamen who had beaten Przemyk, and agreed with them on a favourable version of their testimony. However, despite the management’s efforts, problems arose. ‘These officers are stupid: I tell them how to testify and they don’t understand anything,’ one investigator complained.

Despite this, the communists continued to deny the facts. Two paramedics and a doctor became victims. Intimidated by the SB men, including threats to kill their loved ones, they became the main defendants in a trial closely supervised by the highest state authorities. In the summer of 1984, they were sentenced to prison terms of several months. They were released sooner due to an amnesty for political prisoners. However, the sentences were only overturned after the political change in Poland. It was also then that evidence of the plainly brutish control of the investigation by the leadership of the Ministry of the Interior finally came to light.

The fatal beating of Grzegorz Przemyk proved dramatic not only for his loved ones. The authorities destroyed the lives of the hounded paramedics and Przemyk’s grief-stricken mother, while ensuring impunity for the direct perpetrators of the fatal beating. In addition to the legal aspect, the communists also took care of the propaganda dimension of the case. Przemyk and his mother were regularly stripped of their dignity in the official press. She was harassed by the SB and its agents until her dying days. Lawyers and other people of good will seeking justice were intimidated. One of the victim’s mother’s attorneys was arrested for several months on trumped-up charges, and criminal proceedings were initiated against another using political motivation. Alongside the murder of Father Popiełuszko and the victims of the early days of martial law, the Przemyk case became the most notorious political crime of the final decade of communist rule in Poland.

In his case, the communists left nothing to chance. A specialist team was formed at the Ministry of the Interior to bring the investigation back on the ‘right’ track. Trusted prosecutors known for their servile attitude towards the authorities and for trying the most notorious political trials were delegated from the prosecutor’s office. In turn, the favourable propaganda aspect of the case was directly supervised by government spokesman Jerzy Urban, a cynic as talented as he was universally hated in the Solidarity underground, who became famous, among other things, for declaring that he would send blankets to the homeless in the USA (this offer was supposed to be a response to the West’s desire to offer humanitarian aid to the Polish People’s Republic engulfed in economic crisis).

Justice that never came

The case of Grzegorz Przemyk’s death is also a source of regret years later because, like other communist crimes, it did not receive proper punishment. No consequences were borne by the people responsible for derailing the investigation into false leads, nor for the Secret Service officers who intimidated witnesses and innocent participants of the May tragedy. There was even a plan to kill the main witness and Grzegorz’s friend, who was held at the police station with him, by making it look like a car accident.

When the proceedings were finally discontinued in 2010, the judge in charge of the case acknowledged with some regret that the ‘communist-era chicaneries had proven successful’. Unfortunately, her words are true. While it was possible to identify the militiamen who had beaten Grzegorz Przemyk quite quickly, the trials resumed after 1989 did not yield satisfactory results. Even when a judgement was handed down, as in the case of the militiaman performing the duties of an officer on duty that fateful night, he was prevented from being imprisoned by his supposedly poor health.

Three years after Przemyk’s death, his mother died. His father and several other people remained, who continued to seek justice. And then there were the poems. The underground Solidarity movement published a volume of Przemyk’s poems in the then illegal circulation. Poems depicting promise as a poet. A stay at a police station ruined his chances of spreading his wings and the volume contains a passage that even sounds prophetic: ‘On the day you come for me / I won’t brush my teeth / I won’t have to change my clothes either / I’ll just put on my shoes / For the long road […] We’ll stand on the edge and without looking at each other we’ll jump / Our shadows will stay – perhaps they’ll turn back / And we’ll fly / fly away somewhere.

Author: Grzegorz Wołk (PhD, employee of the History Research Office of Institute of National Remembrance)

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki