This volume of studies and articles devoted to Józef Piłsudski — his achievements, political concepts and their interpretation, a retrospective of nearly a hundred years, is an important book in the field of historiography of Poland and Central Europe of the 20th century. However, it is no less an achievement in the field of – let’s call it – political science and the related field of what might be called ‘science diplomacy’. That being the case – it is also a noteworthy event in the field of contemporary Polish-Lithuanian relations and international politics.

by Wojciech Stanisławski

It is not uncommon for books that are the fruit of a scientific conference to be heterogeneous in content. There may be issues from various fields raised, individual articles may argue with each other, and the importance and cognitive value of the findings may vary. However, these are usually good books that do not pretend to be bestsellers. Only exceptionally do they cause a stir or reach the desks of politicians and publishers, and it would be most unusual to refer to them in terms such as “landmark” or “fundamental.” This is, however, what has happened in this case. We can assume that it is due to the subject of the book and the circumstances under which the conference took place – both equally unusual.

ed. by Danuta Jastrzębska-Golonkowa, Alvydas Nikžentaitis, Włodzimierz Suleja and Tadeusz Wolsza

Publisher: Institute of National Remembrance, 2020

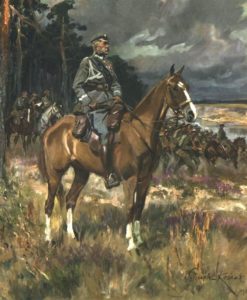

Józef Klemens Piłsudski (to begin with the subject of the book) is widely regarded as a figure who had the greatest impact on the history of Poland in the 20th century. By the vast majority of Poles (which can be concluded judging both public opinion polls and individual declarations, and finally, let’s call it, behaviors and activities in the public area, from publishing books to giving street names) Piłsudski is considered one of the greatest national heroes of the recent past. A socialist and rebel against tsarist power, an exile and conspirator, creator of the first Polish armed forces in decades, namely the Legions established in 1914, a commander, politician and prisoner during the First World War, and when it ended – co-creator of the Polish state and Commander-in-Chief of its army. The unofficial, but undoubtedly, leader of the Republic of Poland from 1926 until his death nine years later, he is a monumental figure in every sense of the word.

His charisma was confirmed by numerous contemporaries, and his strong character, explosive temperament and the references he made to the romantic poetry of the 19th century, do not discredit him in any way. On the contrary, they are to his advantage and are not weakened even by the decisions he made which are considered to be controversial to this day, including, first of all, the armed takeover of the government in Poland in 1926 and all its consequences. Historians are investigating these consequences, which are remembered by the ideological successors of Piłsudski’s contemporary opponents. For the vast majority of Poles it’s much less important. Due to a perspective imposed by mass education, pop culture and in a retrospect of one hundred years, most Poles immediately recognize Piłsudski – with his mustache, bushy eyebrows and short haircut, exploited equally by sculptors and caricaturists. He is often “reduced” to one or several short phrases: “Commandant of the Legions”, “Chief of State”, “co-creator of our independence”, “defender of borders” or, especially in 2020, the 100th anniversary, “conqueror of the Bolsheviks.”

However, one of the consequences of “placing” historical figures in collective memory is – let us put it this way – the blurring of their individual features. Direct witnesses, enemies and followers are gone and have only left us with their memoirs. Over Poland – to use one of Piłsudski’s favorite phrases – subsequent historical storms swept potently. All (or almost all) archives were opened, whatever could be burned, almost certainly did burn. Even if we bear in mind that for the nearly half a century that communists were ruling in Poland, they, depending on the economic situation, hesitated between erasing Piłsudski from collective memory and denigrating him (they had all the necessary tools to do this since they had a monopoly on publishing and practiced censorship), so even though there were so many obstacles, the core of the research was still carried out. Numerous Piłsudski biographies have been written, as well as studies and analyses concerning almost every aspect of his life, timelines have been compiled, and his letters, speeches, and orders have been complied. His memorabilia were collected, there are novels written about him, and a museum devoted to Piłsudski will be opened soon. It can be concluded that the figure of the co-creator of Polish independence in 1918 has finally become homogeneous and monumental – with a distinct bronze shade.

And yet on a certain level the person and achievements of Piłsudski are still controversial. Some arguments are far from academic methodology, igniting violent emotions, sometimes leading to risky conclusions – and are unacceptable to some Poles. The controversy is related to his place of birth, his background and one of the most important political goals he set for himself, namely: Lithuania.

Not only Lithuania – one of the many geographical regions of the Russian Empire, where on 5 December 1867, in Zułów, in the Święciany region, the noble son of Józef and Maria of Billewicz was born – but also historical Lithuania, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, for several hundred years partner in the Commonwealth. However, it was also Lithuania which in the19th century under the tsarist rule experienced a national revival and redefined itself as a community clearly separate from both Russians and Poles.

The dispute that broke out at the beginning of the 20th century between the followers of these three definitions of Lithuania, today almost resolved, aroused at that time great emotions. It led to debates, armed conflicts and alliances crucial to all of Central and Eastern Europe. Positions in these debates were not taken according to the nationality of participating parts. On the contrary, depending on the position taken in this dispute, national identification followed. Part of the elite of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania, aiming at overthrowing Russian rule, dreamed of recreating the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was meant to be a modern form of a Commonwealth, taking into account, to a greater or lesser extent, the national aspirations not only of Poles (which was obvious), but also of Ukrainians and Lithuanians, and – the least emancipated Belarusians at that time. For the other side taking part in the dispute, it was obvious to establish a Lithuanian national state.

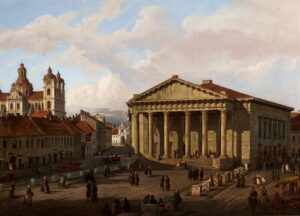

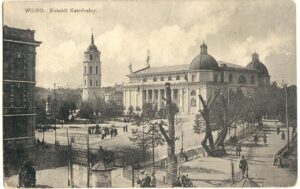

It is difficult to imagine these two sides being reconciled even if they were sitting and discussing at one table – and more difficult if we bear in mind that St. Petersburg was not sovereign any longer and that formerly subordinate lands were gaining independence. The main subject of the dispute were the territories, borders, material and cultural goods, and above all the jewel in the crown, the former capital of the Grand Duchy – Vilnius.

Józef Piłsudski’s position in the dispute was unambiguous and rather radical. He described himself – sometimes half-jokingly, sometimes quite seriously – as “Lithuanian”. At the same time, however, he felt connected, intellectually and emotionally, with the legacy of the pre-partition Republic and with desperate efforts to regain independence which were equally shared by the nobility of the “ethnographically Polish” and “ethnographically Lithuanian” lands. Free of the polonization aspirations shared by many Polish nationalist politicians, he respected the ethnocentric Lithuanian identity and (to some extent) the aspirations related to it. However, he could not imagine that Lithuania would not form a federation with Poland. He changed his attitude as he considered (in the wake of the collapse of the tsarist empire, the Bolshevik revolution and the several wars in Central and Eastern Europe in 1917-1921!) various forms of federation, autonomy, and separateness of Lithuania. However, it was unacceptable for him that Vilnius – the capital of Polish Romanticism – would not be included within the reborn Republic of Poland.

His point of view was unacceptable for the Lithuanian political elite. Thirsty for their own sovereign state, they treated most Polish political proposals (certainly federal ones) with detachment and doubt, and recognized Vilnius – not without reason – as the capital of historical Lithuania and the center of the Lithuanian national revival.

In the uncertain post-war conditions and, as a result, the need to rely on facts, achieving a compromise proved impossible. In the autumn of 1920, when the borders were being shaped after the victorious war against the Bolsheviks, Piłsudski decided to take Vilnius by force. The last attempt to establish autonomy, i.e. Central Lithuania, in view of the refusal to cooperate with any influential politicians of Lithuanian nationality and the incorporation aspiration of the majority of the Sejm of the Polish Republic, also turned out to be an ephemera. In April 1922, it was finally incorporated into the Polish Republic. Vilnius became an important Polish administrative and military center, and confirmed its role as one of the centers of Polish culture, science and spirituality (but also, it should be added, Belarusian and Jewish). This fact, however, was a source of regret and frustration of the Lithuanian political elite, for whom, regardless of the deep political differences between the Christian Democrats, nationalists and leftists, the common belief was that Vilnius must be within the Lithuanian state. The constitution was symbolic: both the constitution adopted by the Sejmas in August 1922, and the one cut down after the coup by President Antanas Smetona in May 1928 did not give Kaunas (the actual seat of the central authorities) the statute of “the capital of Lithuania”, leaving this dignity to Vilnius. Lithuania was separated from Poland by anger and a strip of plowed land; until the mid-1920s, both countries remained in a quasi-war state. They did not establish diplomatic relations until 1938. These breakthroughs took place by pressure and a kind of diplomatic blackmail of the Polish side. On the other hand, Lithuanians remembered Piłsudski as a bête noire (also in radically different post-war conditions) – a “traitor”, who “took” Vilnius away from Lithuania, their Vilnius.

* * *

The above introduction is necessary in order to understand the importance of the conference dedicated to the 150th anniversary of Piłsudski’s birth, which took place on 5-6 December 2017 in Vilnius. Of course, this was not the first debate or the first “round table” of Polish and Lithuanian historians, devoted to the “three definitions of Lithuania” that appeared at the end of the 19th century, the relations of the two states and nations in the 20th century or the policy of Józef Piłsudski. For the first time, however, the debate was to take place at such a serious level, and for the first time it was not so much to allude to the most contentious issues as to refer and respond to them.

Both sides, supported by numerous political and diplomatic institutions (Polish Institute in Vilnius, Embassy of the Republic of Poland in Vilnius, Polish Office for War Veterans) and academic (Institute of National Remembrance, Institute of Lithuanian History, Faculty of History of Vilnius University, Institute of History of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Józef Piłsudski Museum), met the challenge. The most outstanding researchers took part in it and they agreed on the parity of thematically convergent papers. And finally, there was a debate of six historians on a key topic: “Is a Polish-Lithuanian dialogue on Piłsudski possible?”

This book is proof that it is indeed possible. Among the sixteen texts that make up the volume in question there are essays ordering and prioritizing already known facts (“Józef Piłsudski as a Statesman” by Włodzimierz Suleja, “International Relations and Tasks of Polish Foreign Policy According to Józef Piłsudski” by Marek Kornat or “Activity of the Legions in 1914-1918 and the Polish-Bolshevik War in 1918-1920” by Janusz Odziemkowski, regarding Piłsudski’s contribution to the establishment of the Polish armed forces, beginning with the Legions. There is also an equally important essay by Rimantas Miknys, seeking an answer to the question of why, by 1920, Michał Römer, the legendary figure of Polish-Lithuanian relations (an intellectual coming from the gentry family, who for a long time combined “Lithuanian identity” with participation in the fight for Polish independence), was no longer able to cooperate with Piłsudski.

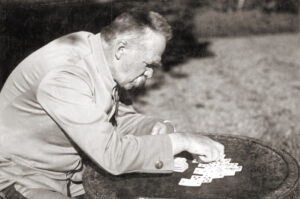

It is significant that among these syntheses the works of Polish researchers dominated for decades dealing with issues “around Piłsudski” and trying to understand them in various ways. The most innovative texts, which shed new light on many issues, were in turn the fruit of the Lithuanian side: I am thinking here of cross-sectional works (“Józef Piłsudski’s ‘Participation’ in Lithuania’s Internal Policy During the Interwar Period” by Arturas Svarauskas or the fascinating study of “The Role of Józef Piłsudski in Diplomatic Relations Between Lithuania and Russia (USSR) in 1920-1926” by Algimantas Kasparavičius) as monographic essays that complement the previously unknown facts on diplomacy and politics: an article by Vytautas Plėčkaitis deserving special mention about the confidential negotiations of the Lithuanian diplomat Jurgis Šaulys and Piłsudski. Of course, similar “monographic essays” were also written by Polish authors; here, however, more often they had the character of petites histoires skilfully juxtaposing already known facts and anecdotes, adding human features to the conference hero, such as the “Passions of Józef Piłsudski” by Tadeusz Wolsza, among which solitaire and chess, which were emblematic for Piłsudski, dominated. Another, a few pages long, but dense with thesis is the valuable essay by the poet and thinker, and veteran of the Polish-Lithuanian dialogue, Tomas Venclova.

Tomas Venclova was also one of the seven participants of the “professors’” dialogue, in which Alfredas Bumblauskas, Marek Kornat, Rimantas Miknys, Andrzej Nowak, Darius Staliūnas and Włodzimierz Suleja also took part. The record of this conversation, moderated by Alvydas Nikžentaitis, is proof that it is possible to talk about Józef Piłsudski in Vilnius in the 21st century without anger, without prejudices and with a great will to understand each other. However, he was a figure of such a format and such significance that it is impossible to talk about him without emotions.

Bez emocji. Polsko-litewski dialog o Józefie Piłsudskim (Without Emotions. Polish-Lithuanian Dialogue About Józef Piłsudski), (ed.) Danuta Jastrzebska-Golonkowa, Alvydas Nikženaitis, Włodzimierz Suleja, Tadeusz Wolsza; Institute of National Remembrance, Polish Institute in Vilnius, Institute of Lithuanian History; Warszawa, 2020.

Author: Wojciech Stanisławski

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin