“In the Battle of the Bulge, during Christmas 1944, the Germans did a lot of damage to the Americans, and the local commanders were complaining loudly about the absence of American intelligence. They turned to the OSS to come up with a remedy”, says John Micgiel. It turned out that Poles were to support this part of the American offensive in the last months of war…

polishhistory: Usually if someone knows something about the Polish intelligence service in the Second World War, one has probably heard about ‘Cichociemni’. The story that you are presenting is completely different. How did you come up with the idea of writing about Project Eagle?

John Micgiel: Way back in the 1980s, I received a grant from the Woodrow Wilson Centre to work in the National Archives in Washington to learn what the Department of State knew about East Central Europe just after the war. In that archive I had a chance to speak to John Taylor, a senior curator, who told me that I should definitely look at a collection that was just being declassified – the Office of Strategic Services records. “You will find a lot there, but it may take a while”, he said. Indeed, it took a long while . In the State Department materials, I found a very laconic reference to something called “Project Eagle”, the Polish job. And that was all there was. So I asked myself “what is this Polish job?”. I returned to it after I retired from Columbia University, when I had the time, and started to research Project Eagle. The book is the result of that research.

So, could you please introduce us to Project Eagle?

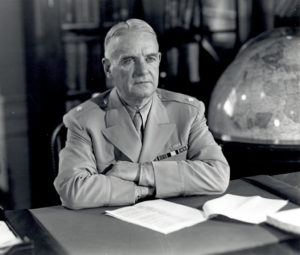

In the Battle of the Bulge, during Christmas 1944, the Germans did a lot of damage to the Americans, and the local commanders were complaining loudly about the absence of American intelligence. They turned to the OSS to come up with a remedy, who in turn did a quick survey of how many of its employees spoke German and could be trained for espionage work in the Reich. They came up with 80 names. General Donovan, the head of the OSS, said that was not enough, and so, in their search for suitable candidates, they turned, among others, to the Poles, who responded that they had quite a lot of German-speakers in their army. And so they devised a plan to bring German speakers into the OSS to drop them into the Reich.

Could you tell us more about the participants themselves? Who were they?

I have to say, they were very difficult to track down, even finding the real names of the 32 gentlemen who took part in this operation was difficult. I was only able to discover the names of about two-thirds of them. They were for the most part, so-called Wasserpolacken who lived in the borderlands, which meant they had at least two identities, German and Polish. They spoke German perfectly, and all of them were forced onto the Deutsche Volksliste [the list containing the people of German or mixed ethnicity living in Poland, conferring various privileges and duties on those listed], and drafted into the German army. We know the names of the cities, towns and villages they were born and lived in. We have some information about their families. There was real tragedy there, as is often the case in Poland. Some of them had fathers and brothers in the Wehrmacht, some had family members in concentration camps. As soon as they came into contact with General Anders’ army in Italy or Allied troops in Normandy, they surrendered. These young men were taken into Allied POW camps, where they were identified by Polish army officers who asked whether they wanted to join the Polish army, as many of them had fought for Poland in 1939. When they agreed they were asked to pick a pseudonym, so that in the case of capture, they would not be shot as deserters. They then volunteered to join what became known as Project Eagle – an idea that was suggested by Col. Stanisław Gano, the head of the Polish intelligence at the time.

What do we know about the way they were preparing for the drop?

Three months were spent in western Scotland, doing physical training — hand-to-hand combat, using explosives, ropework, reading maps and using compasses — the book contains a list of the skills they had to learn. Then they were brought to London, and they learnt about codes, radios, techniques of disappearing in crowds and so forth. They were also being prepared to work for the Americans in occupied Germany after the war. The ‘Cichociemni’ you mentioned were extremely skilled and tough individuals, but the Project Eagle people were trained for much longer and in different techniques.

What did the operation itself look like?

It was a very different experience from parachuting people into France, for example. There Maquis on the ground were ready to receive the agents, relieve them of their equipment and protect them from the Germans. In the case of Project Eagle, the agents were dropped without ground support, and had to expect the presence of the Volkssturm – local militia units, whose task it was to combat Allied parachutists. In fact, two men were killed on landing. Of the rest, everybody survived, and had various kinds of success in obtaining information from forced labourers, and locals. It was a very difficult job.

Project Eagle was a complex undertaking. Can we say that, on the whole, it was successful?

Although technically successful, sadly, it failed to provide the strategic information that the OSS had hoped for. Firstly, there was very little time to establish networks before they were overrun by Allied forces, and secondly because their radios were inadequate. Most broke on impact with the ground, because they were poorly packed, and when the batteries of those that survived the drop ran out, there was no source of electricity to power them because the Americans had bombed the electric grid. The agents gathered intelligence but they could not relay it back to the OSS. Only when they were overrun by the British, Americans, or the French, could they pass on the information that they had. The amazing part of this is that their documents were so well-forged, that even Allied troops whom the agents contacted initially refused to believe they were OSS agents. Only after the intelligence units embedded in different divisions on the front contacted the OSS, did they confirm their identities. They were then picked up by the OSS, briefly interrogated in Luxembourg, and from there to England, where they were more fully debriefed. Some of them were in the field for only a few days or a few weeks. Two men emerged after being out of contact for nearly three months.. Their individual stories were varied, and after they were flown back to London, they were quickly drummed out of the US Army, because their services were no longer needed.

Do we know what happened to them later?

They went back to the Polish army. I’m guessing that most of them wound up working for the Polish Resettlement Corps after the war, and then they just disappeared. The interesting part of the story is that they signed employment contracts with the OSS and one of the items in the contract was that they would never tell anybody what they did during the war, and they never did. No information was revealed by their families, and their records, as was the case with all of the OSS materials were classified as top secret. That didn’t change until just before the death of Bill Casey, who was the head of the CIA under President Ronald Reagan. Casey was head of the Secret Intelligence Branch of the OSS in London in 1945 and it was hewho sent these and other agents into Germany in 1945. Just before he died, he gave a present to his surviving OSS colleagues by declassifying their personnel records.

The story of Project Eagle has long been totally forgotten. What did the research for this book look like?

There are 9 million documents of the OSS in the archives and, obviously, no single person could go through them all. They’re not very well catalogued, so very often you’re looking for a name, or a place where these agents were dropped, or some other indicator that you can make a connection with. That means that doing research is very tedious. The photos in the book all come from the US National Archives, some of which little to do with Project Eagle, but with the OSS Carpetbaggers – the air force of the OSS that dropped agents into France and Germany. There are also some pictures of the agents themselves including photographs for forged German documents, so they required things like capturing the left profile, or right profile, or the face. The forgers took good care of making sure that the documents were just like the originals.

Impressive! Do we know who prepared these documents?

The Polish and British services were very good at it. The agents were dropped in civilian clothes, and they also had to be German-looking, which means that everything they carried with them had to be “German.”

This was a very complicated operation, but not only for technical reasons. The very moment chosen for it was peculiar…

Indeed, it was. Their psychological situation was very tough as well. They were dropped into the Reich after the Yalta conference, and it was public knowledge that Poland was to be moved westward, and that it would be in the Soviet sphere of influence. They also knew that they might not be able to return to their homes because of their service in the OSS, and because of what they were trained to do. So, to confirm that they didn’t return, I looked in the archives of the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) for their pseudonyms, and their real names, and I found nothing.

You’ve made it clear, that the OSS files were essential to your work, but what did you find in the IPN archives? What did you look for there?

First of all I looked for the names of the agents to see if any of them came back by boat. I didn’t find any evidence of that. I did find information about how people who did return were treated in People’s Poland. It wasn’t a pretty picture. They were robbed, their luggage was taken from them as soon as they got off the boat. They could not have had much with them, probably no valuables, but it was all stolen anyway. They were then sent back to their homes and of course they were watched. They had their register with the police, and they were mistrusted. The Polish authorities did not see them as being completely Polish, or at least not Polish enough. They were very poorly treated. That’s what I found in the archives of the IPN.

Did you manage to track down any of the families?

I only found out something about one person, whose pseudonym was “Zygmunt Orłowicz”, his real name was Zygmunt Tydda. His family came from Bydgoszcz, but he was born in Germany, because his father worked for the German Railroads, and he wound up working for an American company in England until he died in 1979. He had two sons, and I came into contact with one of them who provided me with some important details. That’s the only family I was able to find. I spent a lot of time trying to track them down, but it was impossible. I have since learned some biographical information about Jozef Bambynek who also settled in the United Kingdom after the war. Hopefully, this book will evoke responses among the families of other agents.

This is such a complicated story, that it startles me even as a professional historian. You said that there had been a lot of difficult research in archives to be made. Later, you had to do some detective work, and still many pieces are missing, and now you still hope that you will be able to collect some more information.

Yes, I do, but I do not expect that this story will become very popular – it is not for everybody. This is not a grand history of the Second World War. It is not focused on the German Army or defending the Third Reich. This is a story of a group of young men who had a very difficult assignment, and who wound up, at the very last minute, finding out that their country would not be the same country that it was in 1939. Knowing that one cannot return home, that the rest of one’s life will be spent in exile, must have been extremely tough to accept, for these agents, for other Polish soldiers and displaced persons. Did any of these 30 survivors work for the Special Services Unit [the part of the OSS left in service after the war] or the CIA? We don’t know, because the CIA does not normally provide access to its archives. Were there Poles working for the Special Services Unit or the CIA afterwards? Perhaps.

Is this the kind of topic that the American reader would be interested in?

I think that there is a group of specialists who are interested in the subject. For now, however, the book is available only in Polish.

Interviewer: Michał Przeperski