US President Ronald Reagan declared 30 January 1982 to be Solidarity Day. This was both a gesture of support for the citizens of the People’s Republic of Poland and one of opposition to martial law in Poland. However, the White House did not intend limit itself to symbolic gestures.

by Tomasz Kozłowski

In late autumn 1980, Colonel Ryszard Kuklinski started sending intelligence analyses and reports to the CIA, which showed that the communist authorities were getting ready to break up Solidarity. Nevertheless, the White House was surprised by the introduction of martial law. On 10 December, Reagan discussed the conditions for granting economic aid to the People’s Republic of Poland with his staff. Two days later, on the night between the 12th and the 13th of December 1981, tanks appeared on the streets of Poland’s largest cities. Soon after, the “Solidarity” leaders were arrested, and the strikes crushed by the armed militia and military troops.

Initially, Reagan and his associates refrained from making any harsh statements, seeking to understand the situation. Nobody was sure whether martial law was an operation being carried out solely by the Polish army and militia or whether units had been sent – or would be sent – by armies from other Warsaw Pact countries. It was not yet clear how widespread the resistance was among Polish society. Leading members of the Reagan cabinet, as well as the president himself, stated many times that they did not want to cause even greater bloodshed. However, the National Security Council continued to observe and discuss the situation in Poland.

The Cabinet considered several ways of reacting. The most obvious answer was sanctions against Poland and the Soviet Union. However, the scope needed to be carefully thought through, as nobody wanted the sanctions to impact Polish society too hard. With regard to retaliation against the Soviet Union, it was important to convince European allies – Great Britain, France and West Germany – to cooperate and act in unity and coherence. Retaliation was also considered by means of strengthening support for the Afghan mujahedeen but, overall, the number of possible options was quite modest. That is why Reagan believed that the symbolic support of “Solidarity” was very important.

Read more: Solidarity. The 40th anniversary of the birth of the social movement

Evil Empire

For Reagan, the imposition of martial law with the general support of Moscow, was a turning point in the history of the Cold War: “This is the first time in 60 years that we have had this kind of opportunity. There may not be another in our lifetime. Can we afford not to go all out? I’m talking about a total quarantine on the Soviet Union. No détente! We know and the world knows – that they are behind this. We have backed away so many times.” This was not just a figure of speech, Reagan felt strongly in what he was saying. In his private diary, he wrote, “We may never have an opportunity like this in our lifetime.”

Regan’s statements were far from cold realpolitik and instead were full of symbolic comparisons. The struggle of Polish society for freedom reminded him of the history of the first Americans who fought for the independence of their country: “It is like the opening lines in our own declaration of independence. ‘When in the course of human events…’ This is exactly what they (the Poles) are doing now.”

The president firmly believed that this situation made it imperative for the US to redefine its policy towards the Soviet Union. In his opinion, it was a moral obligation foundational to the historic mission of the USA. Reagan alluded to the famous “Quarantine Speech” by Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who in 1937 called for putting a dam to hold back the “epidemic of world lawlessness” sweeping the world. He did not name any country at the time, but it was clear that he was talking about the Axis Powers: the Third Reich, the Kingdom of Italy, and the Japanese Empire. This speech inspired Reagan: “We are the leaders of the Western world. We haven’t been for years, several years, except in name, but we accept that role now. I am talking about action that addresses the Allies and solicits – not begs – them to join in a complete quarantine of the Soviet Union.” Most of the Cabinet supported him. Vice President George Bush stressed that the situation required the US to assume world leadership and Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger shared the same opinion, urging Reagan to deliver the message: “The world needs to be told that it has a leader”. There were discrepancies between cabinet members on the scale of the sanctions, and no one spoke as pompously as Reagan, but all agreed that they faced a public relations challenge.

The strength of a symbol

Jeane Kirkpatrick, the US ambassador to the United Nations and Reagan’s influential adviser, pointed out that the lack of a strong statement so far had not been welcomed by the press. She suggested making symbolic gestures of support and solidarity with Poles every day. The president’s Christmas speech was supposed to mark the culmination of this effort. Reagan himself was aware that no other way out was possible: “I cannot make a ‘Santa Claus is Coming to Town’ speech in this environment.”

Thus, the president prepared his Christmas speech with particular emphasis on Poland. Of course, he first referred to domestic matters, starting with the state of the economy, but then he began to talk about the situation in Eastern Europe. He announced the introduction of limited sanctions against the regime of Wojciech Jaruzelski and also asked his countrymen to light candles in their windows as a gesture of solidarity with Poles.

“For a thousand years, Christmas has been celebrated in Poland, a land of deep religious faith, but this Christmas brings little joy to the courageous Polish people. They have been betrayed by their own government. The men who rule them and their totalitarian allies fear the very freedom that the Polish people cherish. They have answered the stirrings of liberty with brute force, killings, mass arrests, and the setting up of concentration camps. Lech Walesa and other Solidarity leaders are imprisoned, their fate unknown. Factories, mines, universities, and homes have been assaulted. (…) Once, earlier in this century, an evil influence threatened that the lights were going out all over the world. Let the light of millions of candles in American homes give notice that the light of freedom is not going to be extinguished. We are blessed with a freedom and abundance denied to so many. Let those candles remind us that these blessings bring with them a solid obligation, an obligation to the God who guides us, an obligation to the heritage of liberty and dignity handed down to us by our forefathers and an obligation to the children of the world, whose future will be shaped by the way we live our lives today.”

On 23 December 1981, Reagan was writing two texts simultaneously: a Christmas message and a message for Leonid Brezhnev. In the letter, he accused the leader of the Soviet Union of interfering with Poland’s internal affairs and being responsible for what had happened. Brezhnev’s response was sharp – he himself accused the White House of interfering in Poland’s internal affairs, trying to put pressure on the USSR and acting against international law. In response, the White House introduced sanctions against the Soviet Union: exports of high-tech goods were restricted, Aeroflot planes were banned from landing in the US, and negotiations on economic exchange were postponed.

This response was, in fact, limited in scope – the first wave of sanctions hit Moscow after the invasion of Afghanistan. Its effectiveness, as it turned out, was low. The problem was also that European allies were reluctant to join the “quarantine” initiated by the White House. In this situation, even more importance was attached to image-building and symbolic activities.

Let Poland be Poland

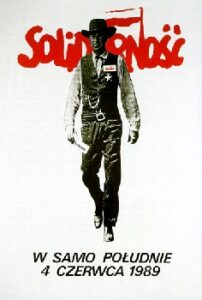

Reagan and members of his administration raised the subject of martial law many times during their speeches. On 20 January 1982, Reagan issued a proclamation declaring 30 January as Solidarity Day – he encouraged citizens to express their support for Polish society and to call for an end to martial law.

The most important event of the day was the broadcast of the “Let Poland be Poland” program, featuring Reagan and a dozen other world leaders, including Margaret Thatcher and François Mitterrand. However, in this 90-minute program, the greatest impression was made by the galaxy of stars who expressed their solidarity with Poles. The program was opened by Charlton Heston, lighting a symbolic candle for “Solidarity”; Max von Sydow presented the history of of “Solidarity”; Czesław Miłosz read a poem; Kirk Douglas recalled his visit to the Film School in Łódź; and Frank Sinatra sang “Free Heart” in Polish and English.

The administration donated money for the organization of this media event, but private sponsors also donated half a million dollars. The program was broadcast by satellite and watched by over 185 million viewers. Another 165 million listeners of Radio Free Europe and the Voice of America listened as well. The White House, encouraged by this success, directed more funds to these radio stations. As a result, the Voice of America broadcast time was extended by seven hours and was listened to regularly by 11 million people.

The sanctions would be effective in the long run but Reagan expected faster results. The administration began to prepare a new global strategy for confronting communism. Poland was only one of the arenas of this struggle and while it was not the most important, it was still key nonetheless. The State Department emphasized that “Poland relates to so many fundamentals (the future of Eastern Europe, the Alliance, Soviet security, American political and moral leadership) that our objectives must be placed in the context of our overall foreign policy. Our overall objective is to maintain U.S. capacity for world leadership by halting and if possible reversing adverse trends in the world power balance over the last decade or more.”

In May 1982, Reagan signed the U.S. National Security Strategy, which was then followed by a detailed strategy of United States Policy Towards Eastern Europe, which paved the way for more decisive action. The CIA launched Operation QRHELPFUL, the aim of which was to support the Solidarity underground.[1] As Seth G. Jones, the author of a book on the subject, assessed: “Neither the CIA nor the White House officials expected U.S. covert assistance to overthrow the Jaruzelski regime or trigger a collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe (…) The goals were limited: to aid the organizational activities of Solidarity and other Polish opposition groups, improve their ability to communicate with the Polish people inside and outside the country, and put more pressure on the Jaruzelski regime to ease its repressive policies.”

See also: December 1980: The Soviet invasion of Poland. Was Moscow really planning to invade Poland?

Solidarity on the global chessboard

During the discussions in the White House after the introduction of martial law, a strategy of confrontation with communism was forged, which was carried out for the entire decade. The Soviet Union was subject to an embargo on modern technologies, numerous trade barriers were created and the debt loop tightened around the countries of Eastern Europe. Enormous funds were devoted to support the mujahedeen in Afghanistan. The Central Intelligence Agency supported “Solidarity” in Poland and its offices abroad – about $20 million was allocated for this purpose.

The policy pursued by the White House towards Poland was, however, always an adjunct of the strategy implemented towards the Soviet Union. Reagan, perhaps even more than his cabinet, was convinced of the moral rationale behind Solidarity. However, global politics was governed by different rules. When the Soviet Union began to decline in 1989, the White House was one of the main global players interested in slowing Poland’s political transformation.

President George Bush, who served as Reagan’s vice president for eight years, was more interested in saving the collapsing Soviet Union than in the Polish revolution. In June 1989, the State Department feared that after the defeat of the communist party in the parliamentary elections, Wojciech Jaruzelski would not run for the presidency. The White House was afraid that Jaruzelski, who had introduced martial law and whom Caspar Weinberger referred to as a Soviet general in a Polish uniform, would not become the president of Poland. In the end, it was George Bush, among others, who had to convince Jaruzelski to take this step.

It was an extraordinary irony. George Bush, had to lend a helping hand to Jaruzelski. “I told him his refusal to run might inadvertently lead to serious instability and I urged him to reconsider. It was ironic. Here was an American president trying to persuade a senior Communist leader to run for office. But I felt that Jaruzelski’s experience was the best hope for a smooth transition in Poland,” Bush recalled years later.

[1] https://polishhistory.pl/a-covert-action-reagan-the-cia-and-the-cold-war-struggle-in-poland/

Author: Tomasz Kozłowski – PhD in political sciences, employee of the History Research Office of Institute of National Remembrance

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin