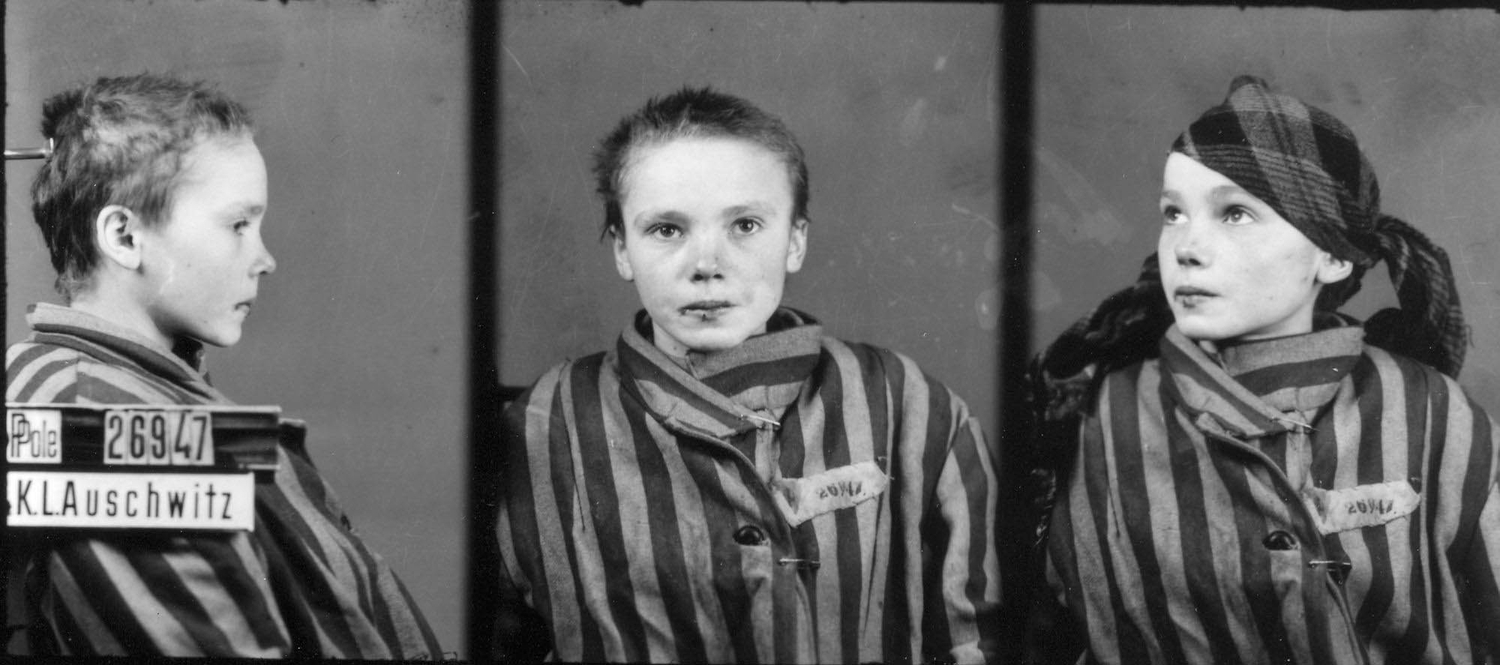

Look at the photo carefully. The face of a Polish girl dressed in the camp’s striped uniform is symbolic of Nazi policy towards children whose lives were considered unnecessary.

by Piotr Abryszeński

The German Generalplan Ost was created on the basis of the assumption that a “living space” (“Lebensraum”) in the territories of Central and Eastern Europe was necessary for Nazi Germany’s development. In practice, this meant the displacement of the native Polish population from those areas where German and (secondly) Ukrainian settlers had been introduced. In line with Heinrich Himmler’s intentions, the first resettlement took place in the Zamość region.

The resettlement, codenamed Aktion Zamość, began in November 1942 and lasted until August the following year. It was accompanied by numerous robberies, murders and rapes of civilians. There were also mass executions, one of the elements of the terror against the local population. The actions of the German authorities led to the outbreak of the so-called Zamość Uprising. The uprising, supported by the forces of the Polish underground, surprised the Germans, but did not stop the deportation. The displaced people were sent to temporary camps, where their further destiny was decided upon.

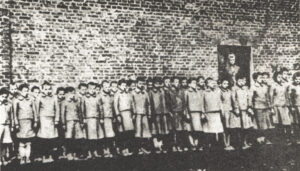

According to historians’ research, over 110,000 people were driven out of their homes there. Over 30,000 of these were children who were separated from their parents and sent for further selection. In the case of any resistance, the German soldiers beat them until they bled. Children who, according to doctors, showed “Germanic traits” were given to German families or sent to orphanages where they were Germanized. Thousands of children who did not meet these criteria were murdered or sent to forced labor deep into Germany or to concentration camps – to Majdanek or to Auschwitz. Poles made desperate attempts to help these children, and even to rescue them from the German hands. Most often, however, these attempts were unsuccessful.

Fighting Auschwitz. A resistance movement in a concentration camp

One of the thousands of children who could not be saved was Czesława (known by the diminutive of Czesia) Kwoka, a 14-year-old Polish Roman Catholic girl. She was born on 15 August 1928 in the town of Wólka Złojecka near Zamość. Her family village was displaced by the Germans in early December 1942. Czesia, together with her mother, Katarzyna Kwoka, were sent to the WZ Lager Zamość transit camp. The sanitary conditions were tragic – children were locked in stables or in unheated and makeshift barracks without bunks or access to medical care. The children slept in the mud, and, according to the memories of witnesses, were overcome with bedbugs and lice. Many of them did not survive. Czesia and her mother were sent to Auschwitz in the first transport from the resettlement camp on 13 December 1942. The girl was given the camp number 26947 (her mother was given the number 26946).

Her innocent and frightened face was immortalized by Wilhelm Brasse, a Polish photographer and prisoner of KL Auschwitz, who had refused to sign the Volkslist, thus ending up in the camp in August 1940. After a few months, the Germans discovered that before the war he had worked as a photographer and decided to employ his skills. He was ordered to take pictures of newly arrived prisoners for the files. The German soldiers also wanted good photos that they could send to their families – a talented photographer took thousands of them. When the Germans started to evacuate and destroy the evidence, Brasse managed to save some of the portraits that are now priceless. After the war, he was unable to return to his profession because, as he recalled, when looking through the lens he could still see the faces of the camp prisoners.

The first mass transport to the Concentration Camp in Auschwitz

Brasse became the protagonist of a TV documentary entitled Portraitist, devoted to his work as a camp photographer. In an interview with Polish filmmakers in 2005, he said that he remembered Czesia well. It is significant because as a camp photographer he saw tens of thousands of faces, including many children.

He mentioned that the girl was terrified and upset. She didn’t know where she was. One of the SS-Aufseherin, German supervisors, had beaten her with a whip or a stick for not understanding the commands in German. Perhaps the woman officer had told her to simply recite the camp number? Or maybe she had given her an order or asked her to answer a question?

The preserved photo shows signs of the beating. The face is swollen, there are traces of blood on the lips and the eyes are in tears. The girl wiped her face just before taking the photo. Her hair is cut short and rough. Next to the plaque with the camp number attached to the teenager’s striped uniform, a red triangle was sewn, which the Germans used to mark political prisoners. There is a letter “P” on the triangle, which meant the teenager’s nationality. Brasse always took three portraits of a prisoner: in profile and en face. The photo of Czesia could have been taken shortly after her arrival in Auschwitz.

We only know that she died on 12 March 1943, a few weeks after her mother’s death. She was probably murdered with a phenol injection. This is how unnecessary prisoners were disposed of.

The Volunteer: One Man, an Underground Army, and the Secret Mission to Destroy Auschwitz

Of the over thirty thousand Polish children from the Zamość region who survived the war after being abducted by the Germans, only about eight hundred were brought back to Poland after 1945. Most of them did not survive. How many old people today are not even aware of their origin?

Author: Piotr Abryszeński – PhD, employee of the History Research Office of Institute of National Remembrance

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin